Glenroe, my native place, sits on the border between Limerick and Cork and hurling and athletics were always very strong in the area. In Canon Sheehan’s famous novel, Glenanaar, there is a fabulous account of a hurling match between neighbouring border rivals which took place in or around 1840. The game, which attracted a huge crowd, was played between the Cork side, known as The Shandons, and the Limerick side, known as The Skirmishers. The game is being fiercely contested until the captain of The Skirmishers is taken ill, and he can play no further part in the battle. There is a famous intervention by a local, known as The Yank, who has recently returned to his native place after spending many years in the USA. The Yank agrees to replace the injured captain of The Skirmishers, and he saves the day and a hard-fought victory is won. After the heroics of The Yank, an onlooker is heard to say that ‘there was nothing seen like that since Terence Casey single-handedly bate the parishes of Ardpatrick and Glenroe’.

********

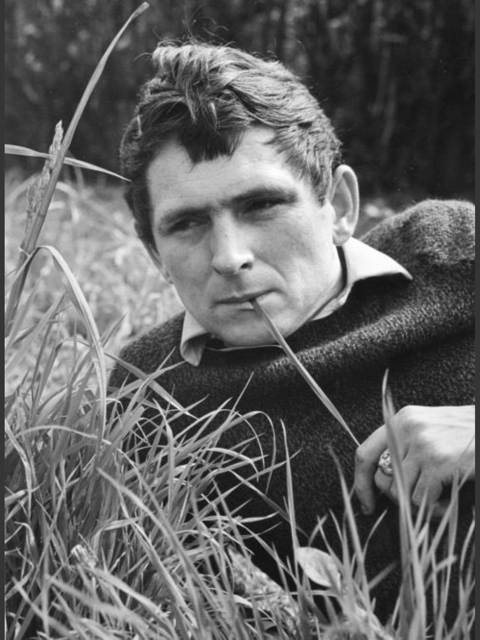

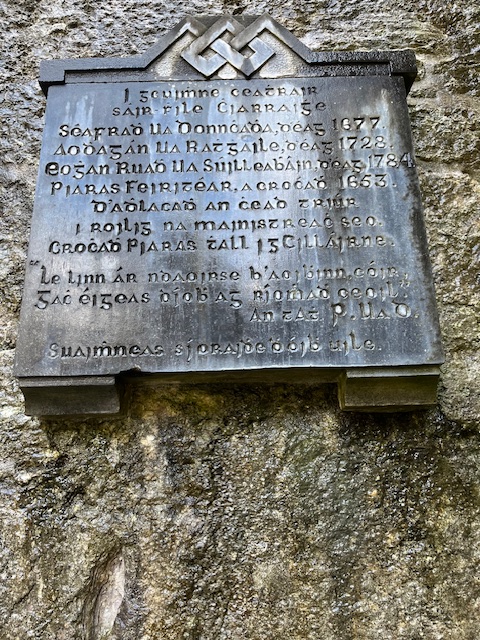

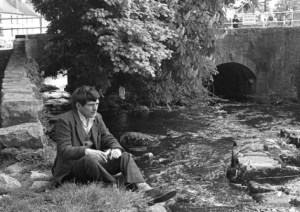

Knockaderry, too, has flirted with fiction. Séan Ó Faoláin was one of the most influential figures in 20th-century Irish culture. A short-story writer of international repute, he was also a leading commentator, critic and novelist. He was the son of Bridget Murphy from Loughill East and Denis Whelan, an RIC constable who had been stationed in the RIC barracks in the village of Knockaderry in the 1890s. Every summer until he was 17, the young Ó Faoláin came to Rathkeale, to Knockaderry and to Loughill East on his holidays. He wrote with great passion about these local places in his autobiography, Vive Moi – and his first novel, in 1933, A Nest of Simple Folk, was based on that disputed territory over the hill betweenà Knockaderry village and Rathkeale, encompassing the landmarks and characters of Loughill East, Balliallinan Kilcolman, Duxtown and as far as Wilton Hill. Ó Faoláin called his home in Killiney, Co. Dublin, Knockaderry.

**********

Glenroe and Knockaderry have long been central to my life. When I left Glenroe to go to boarding school in 1965, I really didn’t intend ever to return there unless I had a very good reason. Yet, fate played a hand, and my daughter Mary met and married Mike O’Brien, and they set up a home which nestles halfway between the parish church and the school. So, in recent years, I have come to cherish the second chance that I have been given. Likewise, I quickly fell in love with Knockaderry when I arrived there in 1977 to take up my first real teaching job in nearby Newcastle West. Both places hold a special place in my heart. Both places would be perfect settings for a good novel!

I love reading, and as a teacher of English literature, I have been doubly blessed in having the honour of introducing my students to some of the great fictional works written. Being a Harper Lee fan, I remember waiting for the much-anticipated publication of Go Set a Watchman in 2015. Written before her only other published novel, the Pulitzer Prize-winning To Kill a Mockingbird (1960), Go Set a Watchman was initially promoted as a sequel by its publishers. It is now accepted that it was a first draft of To Kill a Mockingbird, with many passages in that book being used again. The title alludes to Jean Louise Finch’s view of her father, Atticus Finch, as the moral compass (“watchman”) of Maycomb, Alabama, and has a theme of disillusionment, as she discovers the extent of the bigotry in her home community. Go Set a Watchman tackles the racial tensions brewing in the South in the 1950s and delves into the complex relationship between father and daughter. It includes treatments of many of the characters who appear in To Kill a Mockingbird.

I had already formed a mustard seed theory in my brain that the real-life Monroeville, Alabama, of her youth became the fictional Maycomb, Alabama, of her novels. To me, Maycomb didn’t seem too different to my own special places. Lee had set her novels here for a reason: she deliberately selected her setting, and in effect, the fictional Maycomb becomes another Narnia or Middle Earth – a microcosm of all that is good and bad in 1930s America. She tells us that one went to Maycomb, ‘to have his teeth pulled, his wagon fixed, his heart listened to, his money deposited, his soul saved, his mules vetted’. She describes it as an isolated place; in effect, it is an Everyplace – the place, ‘had remained the same for a hundred years, an island in a patchwork sea of cotton fields and timber land’. It is, in effect, a remote backwater bypassed by progress, the perfect playground of her youth, the perfect setting for a novel and the perfect cauldron for change.

In Go Set a Watchman, she says that Maycomb County is ‘a wilderness dotted with tiny settlements’; it is, ‘so cut off from the rest of the nation that some of its citizens, unaware of the South’s political predilection over the past ninety years, still voted Republican.’ It is so remote, ‘no trains went there’. In actual fact, Maycomb Junction, ‘a courtesy title’, was located in Abbott County, twenty miles away! However, she tells us that the ‘bus service was erratic and seemed to go nowhere, but the Federal Government had forced a highway or two through the swamps, thus giving the citizens an opportunity for free egress.’ However, Lee tells us that few took advantage of this opportunity! Then, in one of those Harper Lee epiphany moments, one of those lightning bolts she releases now and then, she perceptively describes her hometown, and, indeed, my own home place, whether it be Glenroe or Knockaderry, as a place where, ‘If you did not want much, there was plenty.’

In To Kill a Mockingbird, she continues in the same rich vein. Maycomb is a ‘tired old town’. People moved slowly, ‘they ambled across the square, shuffled in and out of the stores around it, took their time about everything’. She tells us that, ‘There was no hurry, for there was nowhere to go, nothing to buy and no money to buy it with, nothing to see outside the boundaries of Maycomb County’, a scenario somewhat reminiscent of modern-day Knockaderry or Glenroe!

Similar to Maycomb, the setting of George Eliot’s novel, Silas Marner, has many similar echoes. The Raveloe described by Eliot is reminiscent of my beloved Knockaderry! She tells us that it ‘was a village where many of the old echoes lingered, undrowned by new voices.’ She further describes it as being, ‘Not …. one of those barren parishes lying on the outskirts of civilisation —inhabited by meagre sheep and thinly-scattered shepherds: on the contrary, it lay in the rich central plain of what we are pleased to call Merry England’. However, like Maycomb and Knockaderry and Glenroe, it was off the beaten track, ‘it was nestled in a snug well-wooded hollow, quite an hour’s journey on horseback from any turnpike, where it was never reached by the vibrations of the coach-horn, or of public opinion’. In Chapter One, Eliot declared it to be a place where bad farmers are rewarded for bad farming!

This description of Raveloe also holds great echoes with The Village as depicted in Jim Crace’s (supposedly last?!) novel, Harvest. The narrator, Walter Thirsk, tells us that, ‘these fields are far from anywhere, two days by post-horse, three days by chariot before you find a market square.’ Harvest dramatises one of the great under-told narratives of English history: the forced enclosure of open fields and common land from the late medieval era on, whereby subsistence agriculture was replaced by profitable wool production, and the peasant farmers were gradually dispossessed and displaced. ‘The sheaf is giving way to sheep’, as Crace puts it here, and an immemorial connection between people and their local environment is being broken – their world is crumbling around them. Great changes are coming and, as everyone knows by now, the only people who welcome change are babies with wet nappies!

Brian Friel’s use of Ballybeg (small town) as the setting for many of his plays and short stories is also similar in vein to these others. In ‘Philadelphia Here I Come!’, Gar Public tells us that Ballybeg is, ‘a bloody quagmire, a backwater, a dead-end’. Friel, like Lee, Eliot, and Crace, is deceptive because he is dealing with familiar things and familiar characters – shopkeepers, housekeepers, and parish priests – a very familiar rural Ireland fixed in its own time. Friel’s use of Public Gar’s alter ego – Private Gar – allows us the opportunity to see behind the superficiality of so much of this world of small-town life.

In many ways, Friel’s major theme is the failure of people to communicate with each other on an intimate level. In his play, ‘Philadelphia, Here I Come!’, we are introduced to the typically Irish practice of verbal non-communication! He, like Harper Lee, George Eliot, and Jim Crace, forces us to examine the nature of society. In Ireland, our society in the 40’s and 50’s was dominated by the church, the politician, and the schoolmaster. Ultimately, the world that Gar is leaving has failed him and his generation. But Friel is too subtle to allow us to imagine that the world Gar is about to enter in Philadelphia will be any better.

These meandering rambles are an attempt to place myself at the beginning of a work of fiction, to stand for a moment in the author’s shoes, so to speak, and see the world from their point of view. From my limited reading, it seems to me that many authors deliberately choose a world untrodden, less travelled as the setting for their novels and plays. I have mentioned some here in this piece, but I’m sure this is just the tip of the iceberg, and you will be able to reference many examples from your own reading.

Ideally, the setting for all these classics is always remote, secluded, off the map, and cut off from change and advancement. This microcosm is then filled with characters and fictional dilemmas, action and inaction. I have always been truly fascinated and awed by each author’s unique ability and ingenuity in creating and imagining these hidden worlds in their heads, and thus allowing us to enter the world of their texts. Knockaderry and Glenroe, apart from their initial flirtations with Séan Ó Faoláin and Canon Sheehan in past centuries, patiently await their twenty-first-century novelist to arrive!

Believe me, the characters are there!

You must be logged in to post a comment.