“I have confidence that there will be a solution (to the Northern Ireland conflict), maybe by the year 2020 when we all have 2020 vision” – Seamus Deane

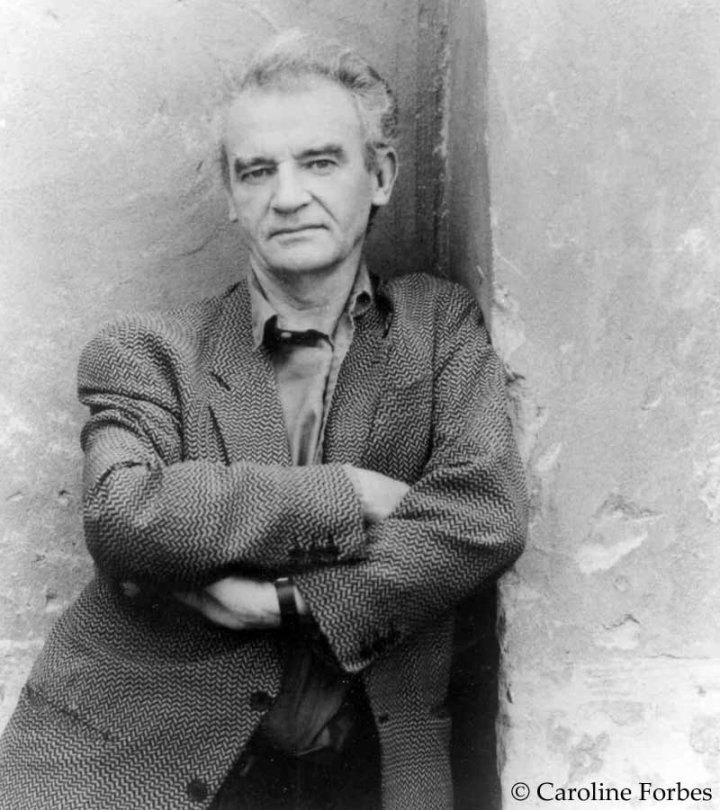

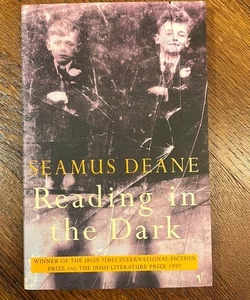

Reading in the Dark has attracted enormous critical attention and acclaim: ‘we are in the territory of the power of the word’ (Anne Devlin, The Independent, August 1996); ‘a thriller of such enigmatic depth that even when all is revealed, its mystery does not dissolve … a masterpiece of eloquence distilled’ (Laura Cumming, The Guardian, December 1996). Reading in the Dark was the 1996 Guardian Fiction Prize-winner and was shortlisted for the 1996 Booker Prize. A literary critic, poet, and Irish republican, what Seamus Deane wants to represent – growing up in Northern Ireland in the forties and fifties, political treachery, sectarian violence, rumour, hauntings, and family secrets – makes particular demands on the written word, literary forms and on the reader.

The English & Media Centre interviewed Seamus Deane for their publication and video, Three Modern Novels at A Level. In the interview extracts that follow, Seamus Deane throws some light on the writing process, family secrets, and Northern Ireland.

The novel’s landscape is drawn from the intimately domestic, from political history and from Irish legend. This short, original, and captivating book, composed of many self-contained stories or ‘prose poems’ is described by Terry Eagleton as, ‘a working-class, Republican version of Irish gothic … it occupies some transitional zone between fiction and autobiography’ (New Statesman & Society, August 1996).

The writing process: editing memory

This novel was a long time in the making. It began as a series of flash memories that were recounted. Those memories accumulated, and as they accumulated they were written and re-written. Then I realised that the memories actually had a lot of raw material but, like in a movie, by positioning one piece beside another, each actually became more powerful because of its neighbourhood with the other. In fact, the novel, since it was told from the point of view of a young boy, couldn’t proceed by large, sustained blocks; the flash image was part of the key to the structure. The next part of the key was to put the images in certain kinds of sequence that would both make them more powerful in themselves but also attract or seduce the reader into wondering not only what happens next, but what is the relationship between these parts, because you can see a relationship in part, but you can’t see all of it initially, it has to unfold. I use those sharp pieces almost like arranging crystals into patterns until I finally found a pattern that I thought did justice to the narrative. And did justice also to the strange experience of the young boy in actually uncovering something piece by piece by piece, and then only towards the end being able to see the whole thing in perspective.

One of the reasons I called it Reading in the Dark is that one of my earliest memories of reading was reading late at night, lying in bed with my three brothers, two at the top, and two at the bottom. Of course, they would frequently object, and after some altercation, the light would have to be switched off. So I would lie there in the dark imagining the unfinished novel that I’d been reading. So I lay there reading in the dark, in that sense. And then, of course, this is what the kid is doing in the novel, he’s ‘in the dark’ about a family secret and at last, in some ways, he learns to read in that dark, to read the secret, in some ways to his regret.

Differences between poetry and prose

I suppose that, in my limited experience, the outstanding feature in relation to the novel is that the novel must produce a story, a narrative. It may be difficult to follow parts of the narrative, nevertheless everything, in some sense of the word, must be explained. Whereas in poetry I think it is possible to leave a great deal unexplained. Part of the power of poetry is, in fact, in leaving something cryptic and letting it, so to say, leak out slowly in repeated readings for the reader. But if a novel tries to work like that I think it becomes another kind of narrative. The narrative element must have a degree of explanation and self-explanation constantly working within it so that the reader knows where he or she is at any given point.

And there is a relationship between the writing of this novel and the writing of poetry for me. There are a number of poems that I’ve written, published years ago that bear directly upon this novel and in fact, I think I might have raided one of those poems for a phrase or two on occasion. But once I’d decided to structure the novel in these little carry on pieces then what I wanted to do was to intensify each piece as much as I could so that it would have what poetry very often has, this strange combination of being very exact, very finely edged, and yet at the same time somehow amorphous. It’s as if you can see something clearly through a mist, that kind of relationship that most poetry can generate. It’s like a resonance, it’s like striking a musical instrument, striking a key, and then hearing, if you had the ears to hear, that the echo went on and on and on.

Writing the truth

I wanted to present the novel as a reflection of the way in which a child would see the world. But I also wanted to present the novel as something which is dealing with this strange and elusive thing called the truth. I wanted to transmit to the reader that there’s certainly a connection between knowing the facts of a situation and knowing the truth of a situation, but that the facts and the truth are not entirely coincident one with the other. And it’s that strange, sometimes distorted relationship between fact and truth that I wanted to gradually expose, because by the time all the facts are in, the truth of the young boy’s situation, he is in combat with the demons that have been released by those facts, and he doesn’t know. I mean there are some things he doesn’t really know and can’t know, because they’re not known at the level of fact. So it’s that kind of interconnection that is part of the reason for the way the novel unfolds and exfoliates, inch by inch, and not, apparently, in chronological sequence. But there are other sequences besides the chronological and they’re deliberately there, in order to say, the fact is here but the truth of that fact is larger than the fact.

My mother saw one section of the novel before she died. Her first reaction was, ‘Well, that’s very nicely written.’ And then she said, ‘But of course it’s not true.’ And then she said, ‘When did you hear all of this anyway?’ And I said, ‘Well, in fact, everything you’ve just read I heard from you, you told me all that.’ This was the section about the grandfather and the policeman, who was put over the bridge. And she said, ‘I didn’t tell you that.’ But I know she did. Then later she came back to me and said, ‘Well, whatever the case, just don’t ever publish it.’ And I said, ‘Okay.’ But I said to myself silently, not while you’re alive, no, I won’t. And I couldn’t publish it when other people were alive, not only my parents. I could have written it, but I couldn’t have published it before their death.

Secrets and lies

I was concerned about exploring a love relationship between my parents, and I was concerned about exploring something in that love relationship that I knew carried a shadow. From the beginning the mother tells the boy there is a shadow, there’s a shadow on the stairs. Of course, stories about ghosts and shadows are frequently used, certainly in Ireland, as code stories for other things that are taboo. Things like stolen children. Children stolen by the fairies are very often a coded way of talking about a woman who abandoned an unwanted child.

So I knew that in some way the heart of the story was the relationship between the parents. I knew that in some way that relationship harboured a secret, and as the boy in the novel discovers, it’s a secret of such intimacy that his entering into it is interfering with it, exploring it. Actually, it damages the relationship between his parents. That’s where his sense of terrible guilt ultimately comes from. The two people he loved, not only loved them but loved the fact that they loved one another. He loved them for loving one another, and then he destroys or damages that love relationship. I suppose it was that I wanted to explore. I really think that kind of relationship is, now I’m guessing here, more frequently found in political cultures that are troubled, that have had various forms of oppression visited upon them, and therefore have developed modes of secrecy. And those modes of secrecy are not just political, they become also personal. And in the story I’m telling here, the political and the personal are so intertwined that you can’t say where one leaves off and the other begins.

I wanted to write about the process of discovery, but writing about the process of discovery was itself another form of discovery. It was both retrieval of something that I have known and I had experienced, but was also finally coming to terms with it, and to some extent, it was like an act of self-forgiveness. I felt how the child in the fiction feels. In some ways, he has done a profound injustice to both his parents in different ways, and yet he has another feeling that there was no avoiding this. He is and he is not responsible. And I suppose the process of the discovery was not only finding out the various pieces of information, but each piece of information also carried its weight of feeling, of emotion, and it was a matter of finding, finally finding, some way of balancing that emotion. I’m not even sure now whether I’ve done that or not. I’ve had, not exactly second thoughts, but little quivers of doubt that still survive.

Ireland: colonised cultures

The mother’s grief is in some ways aligned to Irish history in that it is something that is real, that is actual and yet that cannot be articulated, cannot fully be represented, even to herself, never mind by herself to others. That’s a maimed condition that is frequent in colonised societies. Ireland knows this problem to an unwanted degree by now. The problem is that in a colonised country you’re always represented by the coloniser, you’re represented in a particular way, you know, through stereotypes of various kinds.

The effect of stereotypes is that they have an almost chemical working; they work within the communities to such a degree that you actually begin to find people behaving according to the stereotype. The stereotype sometimes can be benign, and sometimes malign, but the problem of being stereotyped is that you’re always being represented by somebody else. If it’s a powerful culture that is colonising you, you really have very little space to find some alternative way of representing yourself. You can do it, of course, in a different language, if you have a different language, but if you’re in the Irish condition where you had a language, lost it, and the only language you have is the language in which you’re stereotyped in then you have to take a peculiar position on that language to escape from it. The mother is, in her grief, taking the shock, and the trauma of history into herself, but can find no escape from it.

Treachery and betrayal: the personal and the political

I am saying something about the nature of political struggle and I’m saying something about the mysterious nature of human relationships. The constant element within all of the relationships is that of betrayal. You know, there are a variety of forms of betrayal: there is the outright, coarse McIlhenny kind of betrayal, and then there are all the subtler more seductive modes of treachery which nevertheless are also very deeply destructive. Within a political culture that operates in its militant mould through, what is in effect, a secret guerrilla army, then you have an army that depends upon secrecy. The biggest threat to such an army always is betrayal, and it’s a feature of many insurgent movements, and it certainly has been the case in Irish history, that the traitor is a particularly hated, but also a particularly frequent, creature.

If you have something suppressed, if you have great pressure bearing down upon a community, then within that community there are going to be all sorts of ways of dealing with that pressure of which secrecy is one. And secrecy’s other face is always betrayal. The terrible problem of betrayal in human relationships is that if you are betrayed by someone whom you loved, one of the first effects of betrayal is to make you feel, ‘I never knew that person’, ‘I don’t know her’, ‘I don’t know him’. And that person suddenly loses substance and becomes almost shadowy. That is one of the functions of shadows within this novel. Something that’s real and yet at the same time unreal, just the way somebody whom you thought you knew can almost instantaneously become unreal to you if you find out that some terrible betrayal has been taking place without your knowledge, and especially if it’s been done over a long time.

Note: Tony McIlhenny is at the centre of the family secret. He betrayed everyone – his lover (the narrator’s mother), his wife (Katie, his mother’s sister) and their unborn child, the IRA, and Eddie (the narrator’s uncle), who was mistakenly executed by the IRA as an informer while McIlhenny fled to America.

Fire and darkness: representations of Derry

The North is a gothic place. Fire, bonfire, violence, ritual, marches, drums, that’s part of the ritual of a very enclosed and a very explosive society. The North is a place dominated by rituals like Orange marches, and bonfires on the 12th of July, the burning of the effigy of the traitor Lundy every December from a pillar. That was one of the things I always remember about December. In fact, Derry is a city that has, as its central story, its great historical story (at least on the Protestant side), of a city besieged by Catholic armies. This man called Lundy tried to open the gates to the Catholic besiegers. So every year, in the heart of winter we see the traitor burned from a pillar on a hill. This giant twenty-foot high figure, always in black, stuffed with rockets, and soaked in petrol, would loll on the pillar before they set fire to it. I remember a dark December day and this exploding traitor on the pillar.

Then we also have our own bonfires on the 15th. August every year. The physical darkness of the place is emblematic of the political condition of the place. All through the novel, there is a link between darkness and fire and intimacy as well as between intimacy and violence. From that distillery fire forward the young child actually sees the city as a city that is in some sense burning, always burning. His mother says when she’s in her distress, ‘There’s something always burning there.’ You can hear the sound of a fire in a society that is breaking down. You can hear the sound of the disintegration if you listen with sufficient care. So that’s why the city appears so dark because it is a city in a dark condition, a condition of entrapment.

Fantasy and realism: form and conventions

Folklore and legend were important in my own childhood. For me, there were two major formal elements in the fiction. There was the kind of element that one would associate with folk telling, and folk stories, and there was the kind of element that one would associate with novels. Now the difference between those two, as famously has been said by somebody, is that a novel understands answers, and gives an answer to a problem, whereas in a folk story, you don’t seek an answer. The listener to a folk story actually simply says, ‘Ah, the wonder of it, the world is a strange place.’ The folk story is full of wonder, the novel is much more rational as a form, and I wanted to keep precisely those two things in relation, one to the other, because that, in effect, is what the young boy is experiencing: the sense of wonder and the recognition that the only proper response to what he’s undergoing is really just to shake his head and say, the world is a strange place.

But then the novelistic element that involves some of those ingredients such as the ingredient of the thriller and social realism and so forth, that’s the element that allows him to ask, ‘Why? What happened? When? Why did it happen? Why didn’t somebody do this?’ And that variety of question is scattered all through the novel. The sense of mystery and wonder that is alongside it is almost an antidote to the questioning intelligence of the young boy. I keep thinking and speaking of this novel as a matter of balancing, crystallising, and patterning so that the various elements which would normally be in conflict, like the element of folk story and novel, come into harmony.

Different literacies: oral cultures

The Northern Ireland I grew up in was a place that for my generation was transformed by the socialist legislation passed by the Labour government in the mid-1940s, especially the Free Education Act. Up until then, it had been really an oral culture rather than a highly literate culture. I had an actual Aunt Katie, the Katie that is commemorated in this novel. One of her functions in life as far as I was concerned was to scare me helpless every night with the stories that she would tell. She would sit on a chair or at the end of the bed, and she would tell stories, some of which she invented, some of which she was passing on, that she had heard.

Later when I went to places like the West of Donegal, to the Irish-speaking areas, I heard some of the Seanachies, as they’re called, the traditional storytellers, telling traditional tales in Irish, and these tales were well known to everybody in the neighbourhood. The people treated the Seanachies the way you would treat a great singer. You know the song, you just want to hear this particular rendition of it, and how he or she is going to treat this. So I remember sitting in a little house in West Donegal, listening to my first Seanachie, and I suddenly realised this is the tradition out of which Katie came. This is the tradition that was still alive when I was growing up but was beginning to be replaced by the tradition of school, education, university, and that sort of thing. I think I was pretty fortunate in that respect, for an overlap of several years the two were intermingled. The oral tradition was very quickly destroyed. It was dealt the death blow by modern media, though it still survived in a residual way in some parts of the West of Ireland. But it doesn’t any longer have the natural life that it once did have, can’t have in present conditions.

The importance of language in Irish history and literature

Language is important in Irish history for a variety of reasons. I mean it has left us in that condition Yeats spoke of once, not of course that Yeats knew the Irish (language), but he says, ‘English is my native language but not my mother tongue.’ That’s a very curious position to be in. The relationship between the language and the search for the integrity of independence is a story about meaning too, because while, of course, there’s great pressure on the Irish to speak English, the people who are most effective in destroying the Irish language were the Irish themselves.

You know, there was the terrible memento of what they called the tally stick, which was on a string and put around the neck of a schoolchild. And if the schoolchild spoke Irish a notch was made on the stick, and when the child went home he was beaten for every notch for having spoken Irish because they were trying to persuade them, your economic future is in the English language. But then of course they realised that this actually was a form of self-mutilation, but too late. It’s a permanent form of self-mutilation and so the mutilation that goes with colonialism, or goes with oppression, also leads to forms of self-mutilation and one of the areas in which it is most powerfully felt, is in the area of language.

I mean there are all sorts of works of Irish literature which are about, you know, somebody starting, unable to speak, and finishing in a condition of great eloquence. In James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man on the first page, Baby Stephen is lisping, he’s mispronouncing words, and he cannot speak, but that novel, a sort of central classical Irish novel, ends with Stephen about whom the story was being told, taking over the story and telling it himself in his own eloquent way. Similarly, in a simple play like J. M. Synge’s Playboy of the Western World, the hero when we first meet him, is a stuttering lout in a ditch, he can’t speak and he comes out of the ditch into the pub, and he starts telling a story which is partly a lie and partly of course the truth. And he becomes more and more eloquent. The more eloquent he becomes the more he discovers he has an identity, he is a person.

There are various other works of Irish literature that are entranced by the notion that you discover your identity through the mastery of language, but behind that, there is the other story, which says to you no-one ever became masterly at something who has not first known incompetence in it. And that’s especially true for the Irish people in relation to the English language. The comic way, in which they have often been represented speaking their English language, becomes stereotyped, which largely belongs to the 19th Century when Irish became in effect, two languages, and where they were very often forcing the syntax of the Irish language into English words, and of course sounding very quaint and strange to English ears. Irish writers became self-conscious, virtuoso players of the English language, a kind of mastery that comes from recognition of previous incompetence.

So there’s a very deep relation between dumbness, aphasia, and eloquence, and something that is not just true in Irish literature, though it’s most definitely true in various other aspects of Irish life, that relationship between astonishing achievement and loss and gain. In some ways in this novel, the child learns slowly that by the time he achieves eloquence, learns the whole truth, the aphasia, the dumbness, the inner articulacy that characterised both his father and his mother, he has passed from their world into that world. But it’s a very expensive journey that he’s undertaking, and it’s dubious whether that form of eloquence is something that one should aspire to. But whether he wants to aspire to it or not, he’s going to get it, it’s inescapable.

That mix of the folkloric, the legendary, the old Irish language, and the connection between the English language, the new legislation, education, and modernity; the relationship between the two is one that is central to the whole way in which the novel produces itself. It’s a work that is about modernity and it’s about, dare I use the weary old word, tradition and a relationship between them, and the painful emergence from a traditional society into the modern era.

Northern Ireland: the future

I can’t say I feel optimistic about the future of Northern Ireland. There isn’t much reason to be optimistic right now in early 1997. I felt perhaps foolishly optimistic for the eighteen months of the ceasefire. We’ve had twenty-eight years of what Brigadier Kitson calls ‘low-intensity warfare’ in Northern Ireland. There have been some profound changes, but not one of those changes actually seems to have the potential to reveal a way of solving or even shelving the problem or the problems that beset the place. I suppose if I have optimism it’s – and this may seem strangely ill-founded to many people – but I think the solution is actually going to come from the paramilitaries.

It has already begun to emerge, I must say to my own surprise, from the Protestant paramilitaries. Very slowly but visibly, they are detaching themselves, disengaging themselves from the traditional forms of unionism. This is not to say that they’re not Unionist, they are, but they’re Unionist in a different way. And I think equally in the Nationalist Republican side, the IRA, especially if Gerry Adams survives as leader of Sinn Fein, some kind of accommodation can be found between the IRA and UVF.

But, it’s a very frail hope, and of course, it could be extinguished by the next bomb, could be extinguished by another assassination campaign beginning. In the very worst year, 1972, starting with Bloody Sunday, finishing with what, 640 people assassinated something like that in that year, I remember the feeling that we were trapped in such a cul-de-sac that the violence would simply go on reproducing itself endlessly and that there was simply no escape route. I don’t think it would ever have quite that feeling of entrapment again but it could. The possibility of there being a solution, at the moment, is quite remote, but on the other hand, somewhere in me, I have confidence that there will be a solution, maybe by the year 2020 when we all have 2020 vision.

– This interview was taken from The English & Media Magazine, No. 36, Summer 1997.

You must be logged in to post a comment.