In late 1980, Hartnett began work on his best ballad, which is most loved and recited to this day, the ‘Maiden Street Ballad’. The ballad stretches out for 47 verses and is a compendium of much of what he had written in prose about Newcastle West in articles for The Irish Times, for Magill magazine and for the local Annual Observer, the annual publication of the Newcastle West Historical Society during the 60s and early 70s. There are also echoes of other local poems such as ‘Maiden Street’ and ‘Epitaph for John Kelly, Blacksmith’ included among the verses of the ballad.

‘Maiden Street Ballad’ was published by local entrepreneur Davy Cahill’s The Observer Press ‘with the help of members of Newcastle West Historical Society’. Copies of the original are much sought after on eBay and elsewhere to this day. It carried a very eloquent dedication, ‘This ballad was composed by Michael Hartnett in Glendarragh, Templeglantine, County Limerick in December 1980 as a Christmas present for his father Denis Harnett (sic)’.

‘Maiden Street Ballad’ contains a number of autobiographical segments. The early stanzas tell us about his childhood days where they rented accommodation first in Connolly Terrace and then in nearby Church Street before making the move to Lower Maiden Street where they rented a room from Legsa Murphy.

We rented a mansion down in Lower Maiden Street,

Legsa Murphy our landlord, three shillings a week,

the walls were of mud and the roof it did leak

and our mice nearly died of starvation.

Probably one of the most notorious segments is the ten ribald verses from 27 to 37 which describe a virtual pub crawl of all of Newcastle West’s 26 public houses which were doing business in 1980. (Michael Hartnett’s 26 Pubs at Christmas!) In another significant segment from verses 16 to 23, he eloquently documents the move from Lower Maiden Street to the new housing scheme in Assumpta Park. These verses portray Hartnett at his best, they are witty, caustic, and often slanderous; his use of hyperbole pokes fun at his friends and those neighbours who were part of that mass exodus from the slums of Maiden Street and The Coole.

Hartnett says that the street finally ‘gave up the ghost’ in September 1951 when most of the inhabitants were rehoused in one of the 60 new houses in Assumpta Park. Hartnett describes the operation, likening it to the hazardous Exodus of the Israelites escaping from Egypt to the Promised Land! Unlike the ‘pub crawl’ sequence which describes in great detail the quirks and peccadillos of numerous characters, including many of his own family, there are only two people mentioned in the ‘move to The Park’ sequence – only passing reference is made to Dick Fitz and Mike Hart, two great stalwarts of the area. Rather this segment describes his people, his neighbours, the real old stock of the town in a richly comic and exaggerated way.

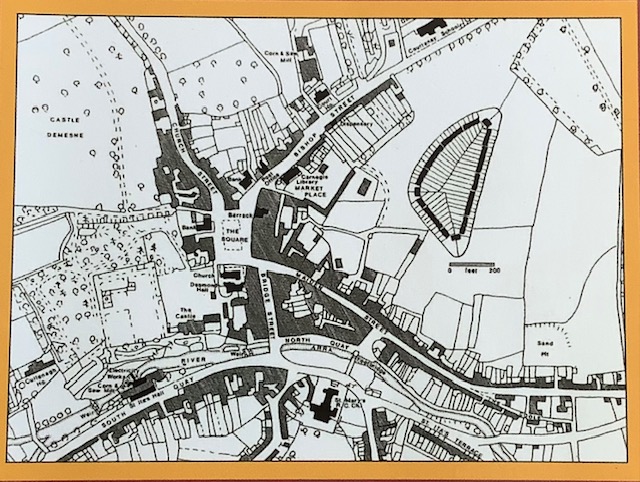

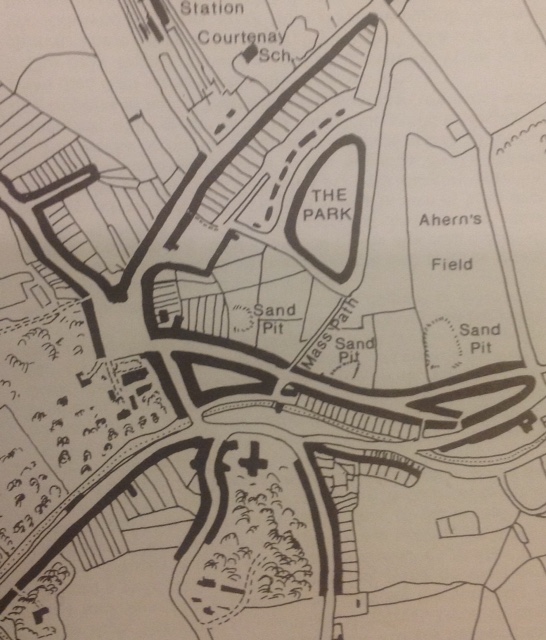

In the late 40s and early 50s, the local authority had built up to 60 social houses to relieve the squalor, poverty and slum-like conditions in Maiden Street and The Coole. They were built in an area of the town known as Hungry Hill, although the new development was officially called Assumpta Park. The Hartnett family were but one of the lucky families to be given a new house and they moved into Number 28 in 1951. Hartnett tells us that the ‘old street finally gave up the ghost’ and the mud-walled, galvanised cabins were abandoned down in The Coole and the people were tempted to move ‘to the Hill’s brand new houses’. The ‘New Houses’ stood on a hill high and exposed above the town at the outer edge of a terminal moraine. The original sixty houses were finally allocated on the 15th of September, 1951. Dr Pat O’Connor, the author of ‘The New Houses: A Memoir’, whose family were allocated Number 24, remembers that ‘doors were still without numbers and entrances without gates’. There was no street lighting or footpaths so it must have been a very eerie place to move to.

The relocation is described in almost Biblical terms with a delicious mixed cocktail of the Exodus story and the story of Noah’s Ark:

and some of the ass-cars were like Noah’s Ark

with livestock and children and spouses.

As well as the Bible, Hartnett is also influenced here by the writings of John Steinbeck and his iconic descriptions of the Great Depression in The Grapes of Wrath as well as the writing of Sean O’Casey and Brendan Behan who wrote about the tenements in Dublin and the gradual movement of people from places like Henrietta Street to Crumlin and Cabra in the 1940s, and Ballyfermot and Artane in the 50.

Hartnett is a very astute commentator on the social ills of his day and the Maiden Street Ballad, and this segment in particular, shows the level of poverty and deprivation experienced by the people in that part of the town in the early 50s. They brought with them their ‘flourbags’, ‘their ‘tea chests’ and ‘three-legged stools’ and their ‘jam-crocks in good working order’. At that time many of the households were so poor that they were unable to afford the bare necessities such as cups and saucers. Jam was sold in one-pound and two-pound glass jars and these were used as substitutes for tea cups and milk glasses in most households. Dr Pat O’Connor tells us that the new occupants had come from ‘the tattered tails of the town, where congestion and dereliction were rife, but (where) the sense of neighbourhood intimacy was well defined’. Hartnett describes the move in a very light-hearted way, and he follows up by saying that they also brought their fleas, bed bugs and mice with them because they felt they were almost part of the family. And now that they’ve moved up in the world the fleas also go to Ballybunion each year on holiday with their host families ‘though hundreds get drowned in the waves there’.

Many found it very difficult to make the necessary adjustments to their new surroundings and the poet pokes fun at their efforts to adapt to such new luxuries as piped water, electricity, toilets and bathtubs. The novelty of two-storey houses had also to be grappled with – three bedrooms upstairs and a hallway, kitchen, scullery and bathroom downstairs. Apocryphal stories circulated that one of the legendary early occupants, Forker O’Brien, famously used the bannisters as kindling for the fire! Indeed, Hartnett would have us believe that many continued with the practices that had been commonplace in their former residences:

In nineteen fifty-one people weren’t too smart:

in spite of the toilets, they pissed out the back,

washed feet in the lavat’ry, put coal in the bath

and kept the odd pig in the garden.

They burnt the bannisters for to make fires

and pumped up the Primus for the kettle to boil,

turned on all the taps, left the lights on all night –

but these antics I’m sure you will pardon.

Hartnett continues in his light-hearted vein, and he lists the great improvements that have come about in peoples’ lives in the years following their relocation. They are respected now and indeed have earned the respect of their fellow townspeople, and they have made great strides to better their situation. Many can now boast of having regular employment, and motor cars and many even go on foreign holidays each year ‘in the Canaries’. The poet’s sense of pride in his own local place is very evident in this section of the ballad and he compares other places he has visited in his travels, but none can compare to his native Newcastle West.

I have seen some fine cities in my traveller’s quest.

put Boston and London and Rome to the test,

but I wouldn’t give one foot of Newcastle West

for all of their beauty and glamour.

In those early days access to The Park was very limited and usually meant a long walk down through the Market Yard or Scanlon’s Lane or down New Road (now Sheehan’s Road) if one wanted to visit friends in Maiden Street or go to Mass on a Sunday. Eventually, representations were made to local Councillors and with the second phase of houses being built in 1955 a Mass Path was constructed which gave residents easier access to the old haunts in Maiden Street and also easy access to the parish church, as the name suggests. The residents of Maiden Street and The Coole were accustomed to being looked down on by the more well-to-do residents of the town and even now, as Dr Pat O’Connor points out, even though the residents of Assumpta Park were in a more exalted and elevated location they found that ‘by a curious process of inversion the people of the town (still) looked down on us’!

Stanzas 22 and 23 paint a moving, nostalgic picture with the poet’s rose-tinted lens firmly in place. We are invited to picture an idyllic scene almost straight out of Thomas Gray’s Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard. It is high summer in Assumpta Park and the visibility is so good you can see Rooska to the north and the Galtees forty miles away to the east straddling the Limerick, Tipperary and Cork borders. All is peaceful and neat and tidy and quiet ‘and the dogs lie asleep in the roadway’. The stanza ends with a beautiful echo of a line from Act 3, Scene 2 of Macbeth – “Light thickens, and the crow/ Makes wing to th’ rooky wood.” (I once heard Noel O’Connor, that great unsung hero and fount of wisdom, say that there’s a quote in Macbeth to solve every problem and cover every possible situation and permutation). Hartnett, in a more benign and domesticated mood, gives us his variation on Macbeth’s more bloody intent:

and the crows to the tree tops fly home in black rows

and the women wheel out their new go-cars.

Dr Pat O’Connor believed that making a new home in The Park was hardest on the women. Yet, as usual, they were the quintessential homemakers. In 1951 scarcely any worked outside the home, often supplementing family income by keeping lodgers or by fostering children, many of whom grew up seamlessly within the various families.

Hartnett’s love for this place is nourished by innocent childhood memories. After all, the poem is meant as a Christmas present for his now ailing father and so he paints a picture which we are invited to contrast with the poverty and squalor of earlier childhood. Hartnett is now forty years of age and remembering life as a ten-year-old in his favourite place, his home in 28 Assumpta Park:

when the smell of black pudding it sweetens the air

and the scent of back rashers it spreads everywhere

and the smoke from the chimneys goes fragrant and straight

to the sky in the Park in the evening.

The residents of Assumpta Park, then and now, are indeed lucky to have as their chroniclers Dr Pat J. O’Connor, one of the most pre-eminent human geographers of his generation, and Michael Hartnett one of Ireland’s great twentieth-century poets. Both have left us their differing yet unique perspectives of an era of great change and of a wonderful social engineering project that worked. Hartnett would definitely point to it as an example that the present government should try to emulate!

Works Cited:

O’Connor, Patrick J. The New Houses: A Memoir. Oidhreacht na Mumhan Books, 2009

Postscript

I came across this little-known poem of Hartnett’s recently which further details the trauma that was involved in the ‘Move to The Park’. There is an Irish version as well.

Off to the New Houses

I was there when the street expired.

When the cabins were put under lock and key;

Gloom and delight were left imprisoned,

The birth-room, the death-room;

And under the floor and on the wall

The mouse and the spider were lonely.

Donkey and trap, wheel-barrow, hand-cart

Safely transporting our ancestral bedding,

My father’s mug, my mother’s sugar-bowl:

We shifted all under cover of night.

And under the floor and on the wall

The mouse and the spider were lonely.

We shifted all that mattered

Except the heart of the old tortured street:

After a pause for porter, my father and his friends went

To move it to us at once.

It was bigger than ten cows’ hearts,

Weals and wounds and scabs all over it.

But its history and grief notwithstanding

There was a living pulse of blood there still.

Late in the night it was put on a cart

And they pulled it across a field

But the heart expired before journey’s end

And we still can’t wash out the bloodstains.

And still under the floor and on the wall

The mouse and the spider are lonely.

Michael Hartnett

You must be logged in to post a comment.