(HAMLET’S CENTRAL IMPORTANCE IN THE PLAY)

‘Hamlet without the Prince’ is a well worn expression for something without significance. In no play of Shakespeare does so much of the effect depend on a single character. It is, of course, quite legitimate to discuss Hamlet’s character, to point to his human qualities, his intellectual bent, his habit of repetition, to probe his ’antic disposition’, and so on. But there is another way of looking at Hamlet and, indeed, at all the tragic heroes. This is to concentrate not so much on what kind of man Hamlet is, but on what he does, what kind of experience he undergoes, what kind of role he must act out.

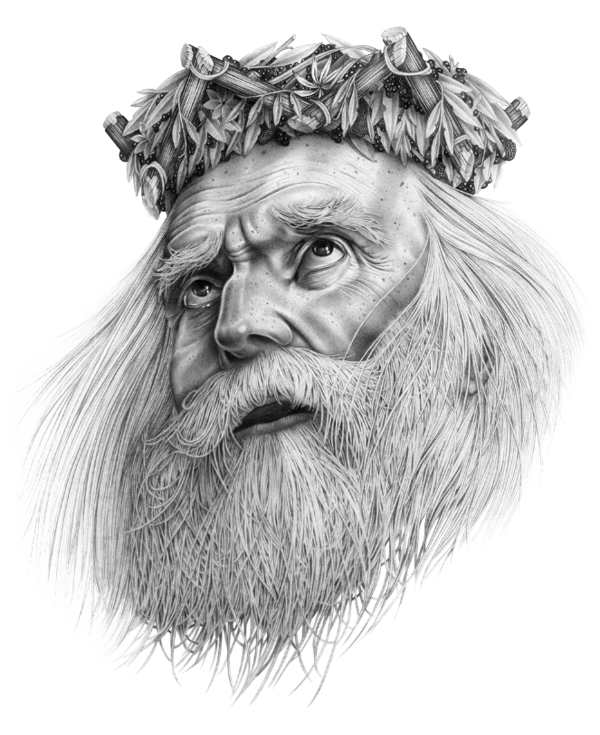

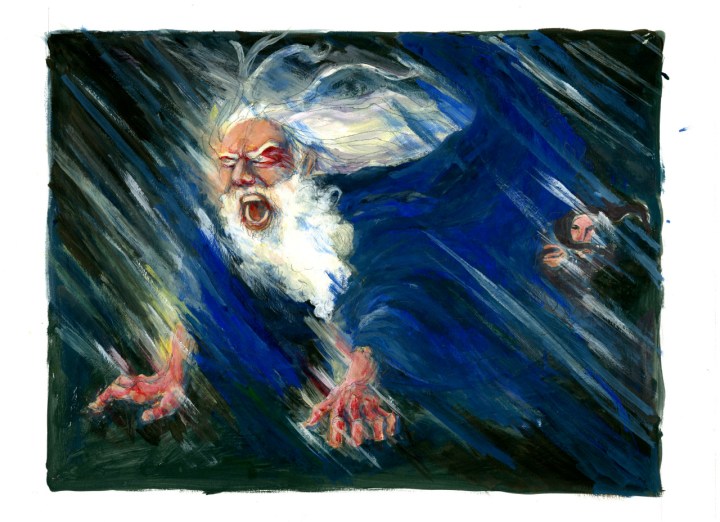

This kind of investigation has the merit of revealing an interesting pattern. A most significant feature of Hamlet’s experience is to pass from one extreme position at the beginning to another at the end, in John Holloway’s phrase, ’from centrality to isolation’ (p. 26). This, indeed, is a common trend in all of Shakespeare’s great tragedies, whether we speak of Lear on the heath, Macbeth isolated in Dunsinane or Othello on the island of Cyprus. Likewise, here in Elsinore, all the emphasis at the beginning is on Hamlet’s central importance. The interest and concern of all the other characters are directed towards him. At the end of the first scene the participants think of him as the only one to deal with the problem they have encountered. ‘Let us impact what we have seen to-night’, suggests Horatio, ‘unto the young Hamlet, for upon my life /The spirit, dumb to us, will speak to him’ (1,i, 169). In the following scene, Claudius and Gertrude accord Hamlet the central place in their deliberations and in their regard, and see him as the man on whom the future of Denmark will depend: ‘You are the most immediate to our throne / And with no less nobility of love / Than that which dearest father bears his son / Do I impact towards you…’(1, ii, 109).

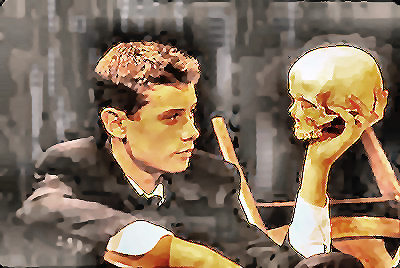

Hamlet’s central position continues to be underlined with the progress of the play. In Act 1, Scene iii, we see that he is the object of Ophelia’s love, and that Laertes is deeply concerned with the relationship. In the next scene, Hamlet is the only one to whom the Ghost will speak. Much of the interest in Act 11 is focused on the attempts of Claudius and Polonius to probe Hamlet’s problems. Hamlet’s privileged centrality at this early point in the play is partly what Ophelia is thinking of when she looks back sadly from a later vantage-point: ‘The expectancy and rose of the fair state / The glass of fashion and the mould of form / The observed of all observers’ (111,i, 152).

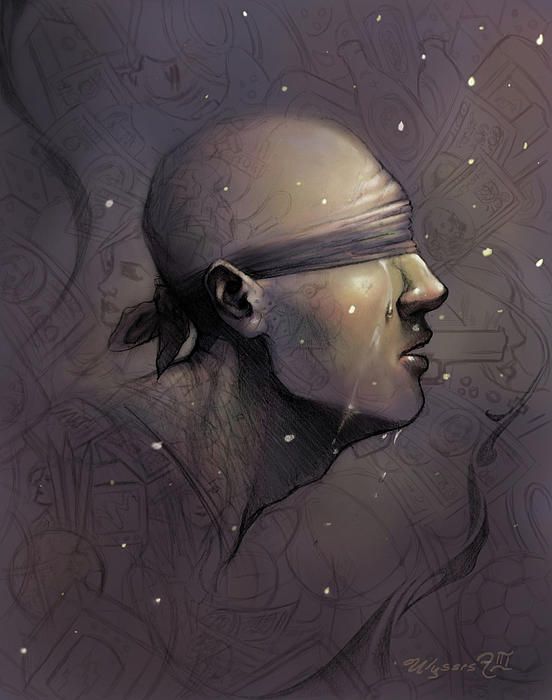

There is, then, considerable concern for Hamlet on the part of all those who surround him, but there is an air of unreality about much of it. The King’s motives are soon suspect: Laertes is not disinterested; Ophelia abandons Hamlet at her father’s instigation. Hamlet still wants to think of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern as his friends, but their friendship, once genuine, is now a mere pretence. He is soon to learn that he can no more trust his former schoolfellows than he can ‘adders fanged’. He is gradually isolated from the comforts of genuine human sympathy; most of those who associate with him (Horatio being the exception), do so for purposes ultimately inimical to his welfare; even Ophelia allows herself to be used by his enemies. There is a real sense in which Ophelia, Rosencrantz, Guildenstern and even his mother have, as John Holloway puts it, ‘all gone over to the other side’. This kind of hostility is, of course, a covert one. It comes into the open in the graveyard scene when Laertes seizes Hamlet by the throat with the cry, ‘The devil take thy soul’ (V, i, 255). In the end Hamlet distances himself even from the loyal Horatio, rejecting his advice not to engage in the duel. The last scene of the play finds Hamlet in the curious position of being isolated and central at the one time; as he fights in single combat, he is surrounded by people who are ranged on the side of his enemy.

Hamlet’s progressive isolation is intensified by his having to take on a well defined role, that of revenger. The demands of the role make him a man apart. The circumstances of the crime he has to avenge, and the various kinds of involvement of the leaders of his society, including his mother, with the criminal he must kill, make it impossible for him to confide in those who should be his natural companions. A man who is given the task of avenging on his own a capital crime, and who must purge evil from a whole society, must inevitably stand outside his social group, and pursue a lonely career until his task has been accomplished. He formally dedicates himself to the role of avenger in Act 1, Scene v: ‘And thy commandment all alone shall live / Within the book and volume of my brain… ‘ (1, v, 102). He knows what his dedication must involve in human terms: ‘O cursed spite / The ever I was born to set it right’ (I, v, 188). He knows that his role as an avenger has set him apart from the others, and imposed intolerable burdens on him:

For this same lord

I do repent; but heaven hath pleas’d it so

To punish me with this, and this with me

That I must be their scourge and minister…

111,iv,173

Problems of character and role are at the heart of Hamlet. One of the favourite themes of critics is Hamlet’s refusal to take decisive action in fulfilment of the ghost’s command. But this is not his only refusal. It might be argued that one of the oddest aspects of the play is Hamlet’s refusal to take a serious part in its proceedings. David Pirie has argued that, ‘the play has to stagger through its five acts without the Prince becoming responsibly involved’ (Critical Quarterly, 1972, p.314). This line of argument is worth pursuing. Hamlet himself makes the point that the ‘real’ world of Elsinore, that rank place of corruption, is an unprofitable subject for serious consideration. His interest in this world, his willingness to participate fully in its concerns, is undermined by his bitter experiences, particularly those involving his mother. And yet, this melancholy and disillusioned sceptic is cast by various people in a number of roles which he is expected to act out with enthusiasm:

- The Ghost has cast him in the role of hero in a revenge play, in which he must kill Claudius and avoid tainting his mind against Gertrude.

- Claudius sees him as the central figure in a drama of political intrigue, plotting against the throne, consumed by ambition.

- Polonius sees him as the suffering victim a tragedy of frustrated love with Ophelia as the heroine.

- The Fortinbras affair tempts Hamlet to accept the role of military hero in a drama of territorial conquest in which he would re-enact his father’s exploits against Norway.

It might be argued that Hamlet rejects all these roles as unworthy of his serious consideration. This rejection is presented by him directly to the audience in terms of a comparison with the theatre in which they find themselves. Hamlet discovers all too evident similarities between the dishonest trappings of Elsinore and the stage of the Globe theatre on which the play is being performed. There are very many theatrical metaphors and explicit references to the stage and acting in Hamlet. Consider the following celebrated speech:

‘Indeed it goes so heavily with my disposition that this goodly frame the earth, seems to me a sterile promontory, this most excellent canopy the air, look you, this brave o’erhanging firmament, this majestic roof fretted with golden fire, why it appeareth nothing more but a foul and pestilent congregation of vapours’ (11, ii, 301).

This speech cannot take on its full significance for a modern reader or a modern audience unless the physical aspects of the Elizabethan theatre are borne in mind. The ceiling of the Elizabethan inner stage was decorated with painted stars and moon; the auditorium was roofless, hence the references to ‘this canopy’ and ‘this firmament’. The Elizabethan stage was shaped like a promontory running out into the audience. Hamlet here expresses his disillusioned withdrawal from his world in terms of the first-hand experiences of the audience. The concerns of the corrupt world of Elsinore, he is telling his listeners, are no more real to him, no more worthy of his serious attention, than the artificial trappings of the theatre are to them. Indeed, there is a sense in which he finds play-acting preferable to the activities of real life, as his comment on the players and their play makes clear: ‘He that plays the king shall be welcome, his majesty shall have tribute on me, the adventurous knight shall use his foil and target, the lover shall not sigh gratis, and the lady shall say her mind freely’ (II, ii, 317).

Each detail here is an implicit comment on the characters of the real Elsinore play. What Hamlet is saying is that the only kings who deserve a welcome are player-king’s; usurpers like Claudius, are unworthy of respect. ‘Foil’ and ‘target’ are a light fencing-sword and light shield, harmless enough weapons compared to the lethal ones of real warriors. In the kind of play Hamlet would like, lovers like him would find their sighs rewarded rather than have to undergo the humiliation he encounters from those who control Ophelia; and in such a play, the Ophelias will be permitted to express their love without constraint. Fortinbras, the nearest approach to a real knight that Hamlet knows, is a reckless adventurer whose activities will result in mass slaughter. His own letters to Ophelia (his ‘groans’) will be read by enemies; their private conversations will be arranged and listened to by eavesdroppers. Every relationship but one in Elsinore in which Hamlet is involved strikes a false position. He has to reject what David Pirie has called the ‘false scripts’ offered to him by the other characters and lure as many of them as he can into a play of his own devising, a play in which, for a change, he can direct matters and replace false seeming by a true representation of events. His adaptation of The Murder of Gonzago into the Mousetrap is much closer to the truth than are the dishonest cat and mouse activities of Claudius and Polonius.

This view of Hamlet’s attitudes to the world of Elsinore, his refusal to accept its standards and to take it seriously, may help to account for his reaction when he finds Claudius at prayer. Here he has his one undoubted opportunity to carry out his father’s command, but he does not avail of it. His excuse is a dogmatic statement about sin and the after-life, to the effect that Claudius will go to heaven if he is killed while in the state of grace. This is less than fully convincing in view of his already declared scepticism on such matters. A more plausible explanation of his attitude here might be that if he did slay Claudius he would be admitting that action was valid, and thus deny his deep-seated belief that life and action are both meaningless. What, then of the killing of Polonius and of the Rosencrantz and Guildenstern affair? One might argue, as David Pirie does, that Hamlet is,

‘sometimes tricked into action by the energy with which other characters pursue their plot. So in blind anger when he thinks that Claudius has been placed by his mother to eavesdrop on their private talk, he stabs through the arras only to find the wholly inappropriate object of a dead Polonius’.

What Hamlet learns from this episode is what he must have sensed all along, that actions don’t always speak louder than words!

Works Cited

Holloway, John, The Story of the Night: Studies in Shakespeare’s Major Tragedies, Routledge Library Edition, 2005. Print

Pirie, David, “Hamlet without the Prince”, Critical Quarterly 14, (Winter 1972) in Shakespeare’s Wide and Universal Stage, eds. C.B. Cox and D.J. Palmer. (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1984). Print

You must be logged in to post a comment.