I’ve always been fascinated by books, although I wouldn’t consider myself a good reader. I’m definitely not a consistent reader, and my iPad constantly berates me for not meeting my daily targets.

When Kate and I began to settle into our new home in Knockaderry, we gradually undertook a series of necessary improvements. The house was a mess, and we often said that there was so much wrong with it that it was no wonder no one else wanted to buy it! In time, we added two bedrooms and a new bathroom, and we converted what had been the second bedroom in the old house into a study. The study soon filled up with books; many were prescribed texts from school.

One of our early purchases was Encyclopaedia Britannica, and we used it as a piece of furniture and a kind of 1980s status symbol for the sitting room rather than as a reference library. It’s still there on the top shelf, out of reach and neglected! This was later added to with the acquisition of World Book Encyclopaedia and Childcraft. When the kids were young, one of Kate’s many jobs outside the home was as an agent for World Book. In my hazy recollection, both sets were very rarely referred to and have remained for years untouched by human hand. They were nearly as neglected as the copy of The Jerusalem Bible, which I purchased in 1982!

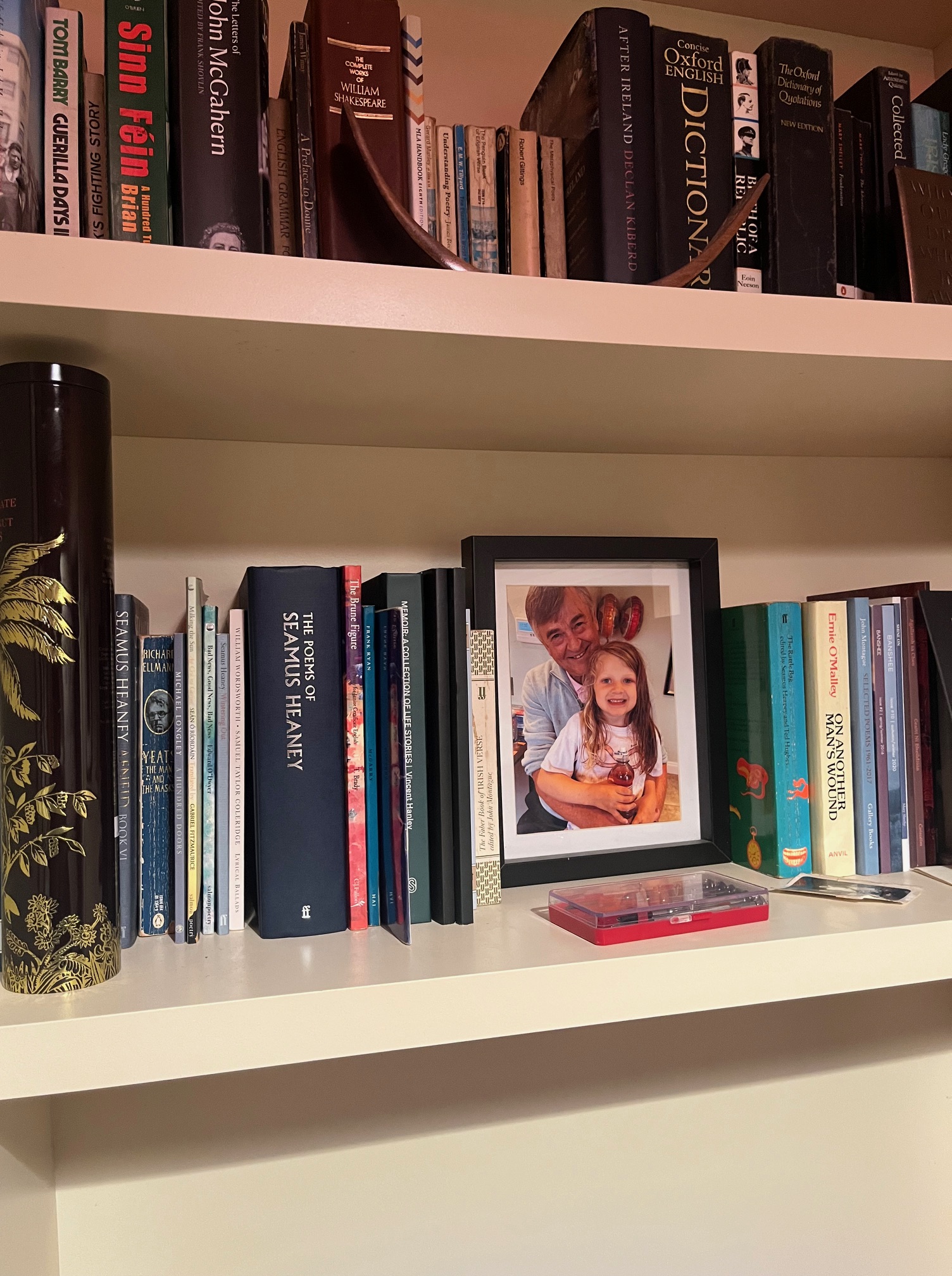

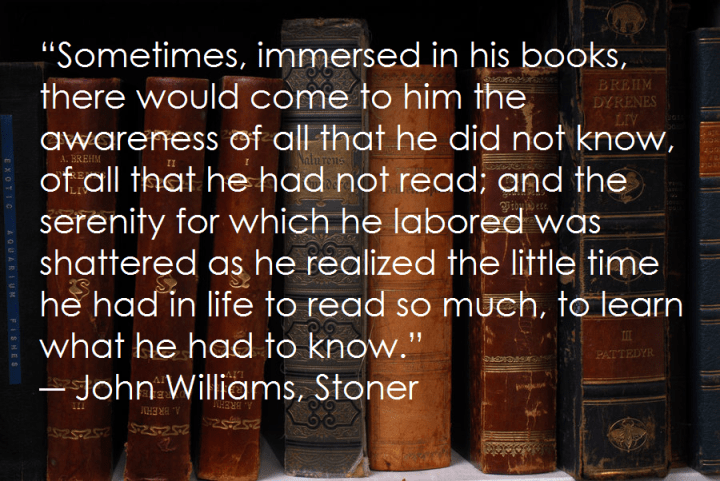

My study is my favourite room in our home – book-lined and snug with its one window looking out upon wind-ravaged, leggy Lawson Cypress. One of my secret joys was seeing Don begin to assemble an alternative library and reading list of epic proportions. And, today, pride of place goes to the remnants of Don’s library, who is a far more serious reader than I am. His adolescent infatuation with Hemingway is still well represented, as are other examples of his voracious and enquiring mind.

I had earlier figured out when I came to stay with my Aunty Meg in September 1977 that the way to find out what was best to read was to locate a great reader and follow in his or her footsteps and Meg fulfilled that role for me and, of course I quickly realised that there are surprisingly very few great readers – they are in fact as rare as giant pandas!

I think I have mentioned earlier that my love of books began in earnest in Fifth Class in Primary school in Glenroe. It was a great honour for me to have been appointed school librarian, and the school library, even though it consisted of a single pine press in the corner of the room, was magical. What mattered was that the press was new and the books were new and had that glorious, magical new-book smell. I felt I had to lead by example, so my first two books borrowed – and read – were Old Celtic Romances by P.W. Joyce and Ben-Hur by Lew Wallace (first published in 1880!). In that pre-television age, I was also fascinated by comics that recounted the exploits of Roy of the Rovers and other daredevil heroes. Looking back now, there was much racist content in those black-and-white comics. The anti-German content in the war stories was criminal, and I began to put a rudimentary German vocabulary together. Words like Achtung! Achtung!, Himmel, etc., were common as the Germans were always defeated and butchered from machine gun nests in the hills. American comics were no less racist, and the indigenous Red Indian population were depicted as savage, uneducated, and primitive in their treatment of the swashbuckling cowboys and their women and children. Those comics were like gold dust, and we swapped them continuously with our friends.

Shortly after this, I graduated to novels, and I remember reading hundreds of Biggles books, novels written by Capt. W. E. Johns, who told of the wartime exploits of Biggles flying mission after mission with his beloved Royal Air Force. Biggles had an unusually lengthy career, flying a number of aircraft representative of the history of British military aviation, from Sopwith Camels during the First World War, Hawker Hurricanes and Supermarine Spitfires in the Second World War, right up to the Hawker Hunter jet fighter in a post-World War II adventure. Enid Blyton was also very popular, and I didn’t consider it beneath me to read her Famous Five books or her Secret Seven stories of adventure and mystery in merry old middle-class England of the ‘50s.

My reading in secondary school was largely determined by prescribed texts, and generally those were dreadful, musty, and dusty, and they relied almost totally on the ancient English classics. Most of the poets were dead, and all the prose writers were long gone to their stuffy library in the sky. University wasn’t much better: in UCC it was Beowulf, Sir Gawain, Chaucer, Spencer, Shakespeare, Donne. Yeats and Kavanagh were mentioned in passing, and we were lucky in the 70s to have a few rebels like John Montague to counterbalance the primness and the staidness of Professor Seán Lucy and Sr. Una Nelly. As far as I could see, UCC and its English Department were firmly rooted in the past. The notion was prevalent then that all good literature was in the past, so we had to find Hemingway, Steinbeck, Salinger, McGahern, Daniel Corkery, Séan Ó Faoláin, Liam O’Flaherty, and Joyce for ourselves! I believe the twentieth century began in UCC around 1980!

Ironically, when I got my first teaching job at St. Ita’s Secondary School in Newcastle West, the school was located in an old Carnegie Library – one of the myriad such libraries dotted throughout West Limerick. So, I taught in ‘The Library’ for 15 years and enjoyed every single minute of it. Needless to say, there wasn’t much spare time for reading, but I tried valiantly to keep up with my main mentor at the time, my Aunty Meg. I stayed with Meg, Jack, Mary and Pat for the two years 1977 and ‘78. She treated me like her fifth son, much to my own mother’s chagrin! She gave me four precious gifts. She instructed me in the intricacies of 45, that distinctly Irish card game; she challenged me regularly to improve my Scrabble skills; she introduced me to the delights of 16-ounce bags of Cherry Brandy flavoured pipe tobacco from America; and she provided me with an endless supply of American blockbuster novels which she picked up on her frequent visits to New York where she went to visit her son, Michael.

Under her mentorship, I read Leon Uris when no one else had heard of him. I was the second person in Knockaderry to read all those bestselling novels, like Exodus, Mila 18, Battle Cry, Topaz, and Armageddon. We also took great interest when he ventured into Irish politics with his novel Trinity (1976) and its sequel Redemption (1995). As a wedding present in 1979, she presented me with Robert Ludlum’s The Matarese Circle, and during the ‘80s, each time she visited Mike, she brought me back the latest of the Bourne trilogy: The Bourne Identity (1980), The Bourne Supremacy (1986) and The Bourne Ultimatum (1990). Twenty years later, Matt Damon made Jason Bourne famous on the big screen, and I was able to say that Meg and I knew every twist and turn of those convoluted plots. She also introduced me to Mario Puzo’s The Godfather, Fools Die and The Sicilian. She also loved the novels of former Champion Jockey, Dick Francis, whose novels were set in the murky underworld that was horse racing, which was centred in and around Newmarket.

I must say that the greatest development in my career as an English teacher was the introduction of the new Leaving Cert English syllabus around 2000. It breathed new life into a language subject that, up to then, was nearly as dead and moribund as Latin. Suddenly, the subject came to life. Now students were studying modern, living writers, and because of the emergence of Irish writing, many of the novels and plays were by Irish writers like Donal Ryan, Sebastian Barry, Joseph O’Connor, Claire Keegan, Emma Donoghue, Brian Friel and John B. Keane. It was a pleasure to teach poetry, which was relevant and vibrant and Irish: poets like Heaney, Mahon, Longley, Kavanagh, Yeats, Boland, Paula Meehan, and Montague were studied avidly.

Here, I have to mention my own favourite book of all time. That accolade goes to Reading in the Dark by Seamus Deane – definitely the best book never to win The Booker! This incredibly well-crafted novel is set in Derry over 16 years, from 1945 to 1961. The book presents a child’s view of the tensions in the city during that time. Throughout the book, we are reminded of the conflict that surrounds the narrator. As a teacher, I got great satisfaction in revealing and solving the mystery and compiling the jigsaw with my many Leaving Cert students when it made its way onto the Higher Level English syllabus in the early 2000s. Deane parallels the personal story at the heart of the novel with the political developments that are taking place in his native Derry. The secrets and mistaken beliefs that divide a family are symbolic of the secrets and divisions that divide a whole people. The author is not a detached observer: the gap between Seamus Deane and the narrator is so narrow as to be almost indistinguishable. The reader is invited to sympathise with the boy in the unique position he finds himself in. I would encourage you, if you can find a copy, to put it on your reading list – you will then be expected to do your fair share of ‘reading in the dark’ also!

If you’d like to explore it further, just click on the link in red. Better still, find it in a second-hand bookstore and read the novel first. See if you agree with me! My favourite Novel of all Time: Reading in the Dark by Seamus Deane

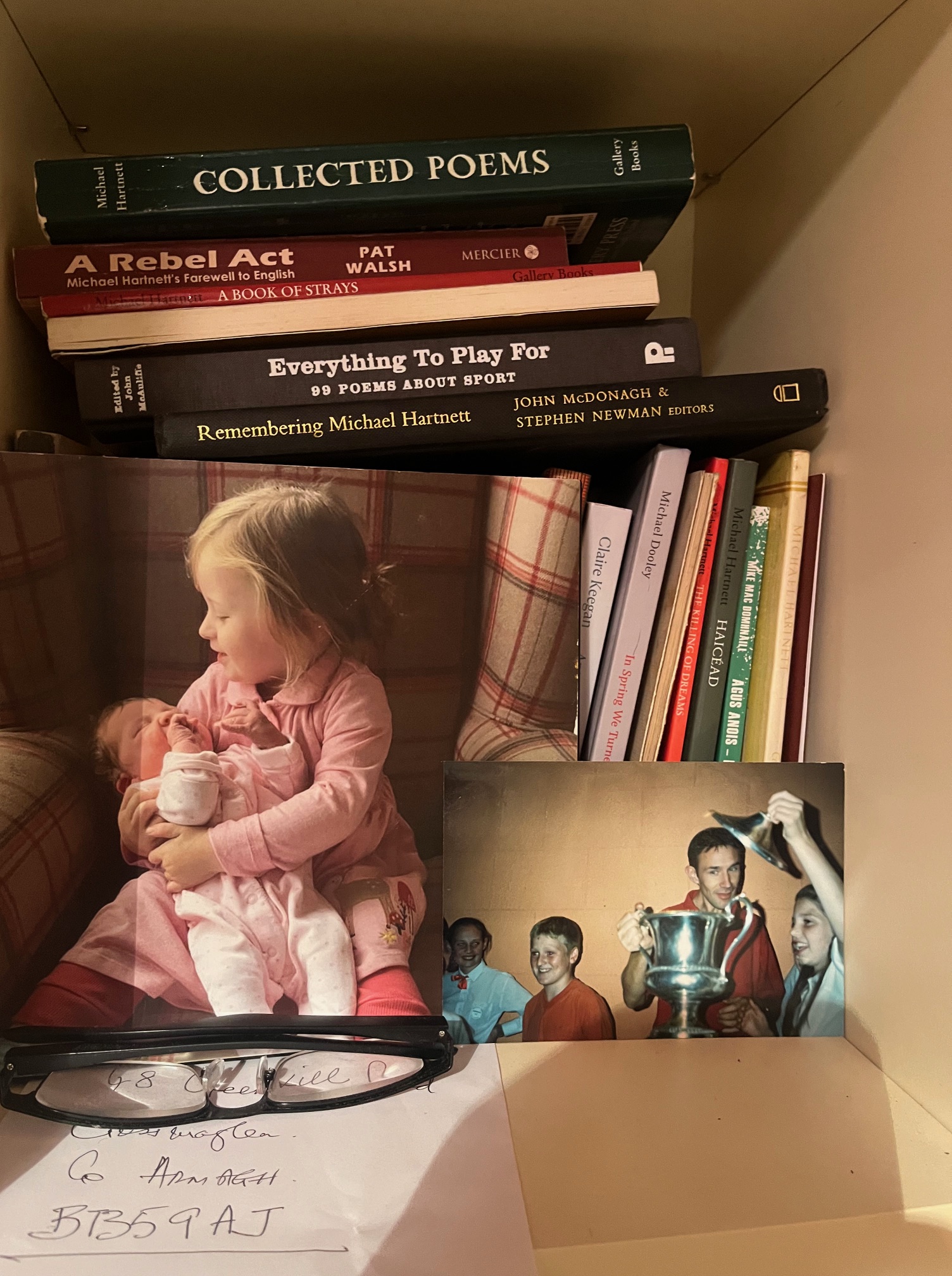

Today, when I travel to Glenroe or Sandymount or beyond, I always have with me in my Roy Cropper black bag my myriad pills and potions and an ever-changing selection of my favourite writers and poets. In the black bag at present, I have Seamus Heaney’s 100 Poems, which was a treasured gift from my daughter Mary, Hartnett’s Collected Poems, and his beautiful 1987 collection, A Necklace of Wrens, along with Michael Dooley’s In Spring We Turned to Water, and Dean Browne’s amazing first collection, After Party.

Reading allows you to borrow someone else’s brain and have a conversation with the most consequential minds in history. However, it’s a learned skill and requires discipline, and you have to set aside time for it. Keep your phone in another room. Always carry a book with you and steal 5-10 minute intervals when you can and avoid audiobooks like the plague! Nothing beats having an actual book in your hands – Kindle, the iPad and other virtual books don’t really count – except in emergencies. Keep as many physical copies (trophies) surrounding you as possible, especially if they are as beautifully produced as Faber and Faber and Picador books. (Faber has done much to make Claire Keegan’s novellas collector’s items; they are so exquisitely produced). The aim is to gradually amass a treasured library over time. These aren’t just books, but tangible links to the very best of literature, history and culture, offering the reader authentic sources beyond the internet’s scattered AI-flawed information.

You must be logged in to post a comment.