THIS IS A PERSONAL REVIEW OF SOME THEMES AND ISSUES WHICH FEATURE IN THE POETRY OF JOHN MONTAGUE. YOU SHOULD CONSIDER THESE IDEAS, THEN RE-EXAMINE THE POEMS MENTIONED FOR EVIDENCE TO SUBSTANTIATE OR CONTRADICT THESE INTERPRETATIONS. IN OTHER WORDS, MAKE YOUR OWN OF THESE NOTES, ADD TO THEM OR DELETE FROM THEM AS YOU SEE FIT.

THE FOLLOWING SELECTION IS SUGGESTED BECAUSE THEY DEAL WITH THE MAJOR THEMES AND STYLISTIC DEVICES WHICH RECUR IN MONTAGUE’S POETRY:

• The Locket (TL)

• The Cage (TC)

• Like Dolmens Round my Childhood the Old People (LDRMC)

• The Wild Dog Rose (TWDR)

• The Same Gesture (TSG)

• Windharp

• A Welcoming Party (AWP)

HE SAID HIMSELF THAT WRITING POETRY WAS ‘LIKE THE DROPPING OF A ROSE PETAL INTO THE GRAND CANYON, A FUTILE ACT’. MAYBE, HOWEVER, YOUR VIEW OF LIFE HAS BEEN CHANGED BY READING HIS POETRY AND MAYBE THE GRAND CANYON IS SWEETER FOR THAT ROSE PETAL AND MAYBE THE WORLD IS A BETTER PLACE BECAUSE OF JOHN MONTAGUE’S POETRY!

YOUR AIM SHOULD BE TO PICK YOUR OWN FAVOURITES FROM THIS SELECTION AND GET TO KNOW THEM VERY WELL.

Relevant Background

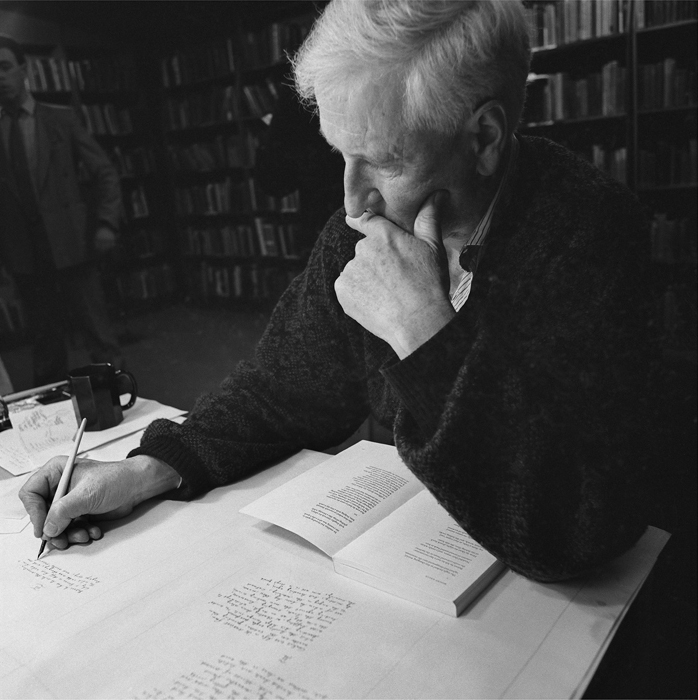

• John Montague was born in Brooklyn, New York early in 1929.

• He was son of James Montague, an Ulster Catholic, from County Tyrone, who had immigrated to America in 1925 after involvement in republican activities.

• His mother was Molly Carney, but she played little part in his life after his birth. Yet she marred John’s life by her absence from it.

• James Montague had the typical exile’s optimistic hope of benefiting from the American Dream.

• But when his wife, Molly, arrived three years later with their two first sons, James could provide nothing better than the Brooklyn slums for their family home.

• Regarding his background, John Montague’s grandfather was a Justice of the Peace, schoolmaster, farmer, postmaster and director of several firms.

• John had a typical Brooklyn kid’s early childhood, playing with coins on tram- lines and seeing early Mickey Mouse movies.

• Because of the economic effects of the Depression era John Montague was shipped back in 1933 at the age of four to his family home at Garvaghey, in County Tyrone.

• John Montague’s mother rejected him after a painful birth. This rejection and marriage problems were contributory causes to the decision to send John to be fostered from the age of four by two aging unmarried aunts.

• Later, when his mother ended her marriage and returned to Ulster, she continued to ignore John, a fact which deeply hurt him and affected both his speech and his ability to socialise with women.

• However, the switch from city kid to country-village boy in Ulster benefited John and proved to be a ‘healing’ as he called it in a poem not on the course.

• With the help of his imagination, he adopted to life on a farm that doubled as the local rural post-office. Because of this he got to know the local characters and gossip very well. We see this in ‘Like Dolmens’ and ‘The Wild Dog Rose’.

• He was first taught in Garvaghey national school.

• For secondary education John went to an austere boarding school run by strict priests in Armagh. There, against his will, John learned about the long tradition of Irish poetry from an influential teacher.

• While studying for his degree in Dublin after World War Two, John found Dublin to be a very old fashioned place, with the atmosphere over-controlled, especially by priests.

• Afterwards he went to work and complete his education in American Universities. He honed his poetic skills while in America.

• John Montague then got married and lived for a time in France where he continued to write poetry and to write short stories. There for a while he became a friend of the renowned Irish playwright, Samuel Beckett.

• He worked as Paris correspondent for The Irish Times for three years. He spent a total of twelve years living in France.

• After journalism, he began a long career as a university lecturer and poet. He has lectured at universities in France, Ireland, Canada, and the United States.

• He is the author of numerous collections of his own poems and editor of anthologies of works of other poets.

• He has received many awards, including the Irish-American Cultural Institute’s Award for Literature, the American Ireland Fund Literary Award and a Guggenheim Fellowship.

• In 1987, Montague was awarded an honorary doctorate by the State University of New York. The State Governor Mario M. Cuomo praised Montague for his outstanding literary achievements and his contributions to the people of New York.

• In 1998, he was named the first Irish Professor of Poetry. This is a position he held for three years, equally divided among The Queen’s University in Belfast, Trinity College Dublin, and University College Dublin.

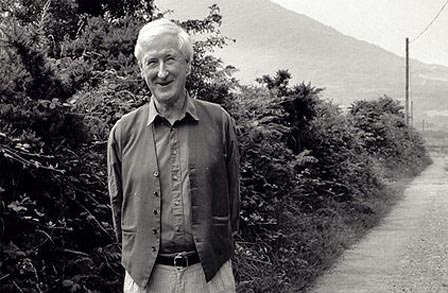

• He now divides his time between West Cork and France.

• John Montague has a major international reputation as an Irish poet, the first major Northern Irish Catholic poet.

• He is a poet who describes private feelings as well as public themes.

• Much of his poetry centres on his personal family history and the culture and history of Catholics in Northern Ireland, including the twenty-five year long period of the Troubles.

• For example, his greatest poem ‘The Rough Field’ is set on the farm where he was reared from the age of four and was influenced by the people he grew up among. Three course poems e.g. ‘Like Dolmens Round My Childhood’ come from ‘The Rough Field’.

• The Civil Rights Movement in 1960s Northern Ireland also influenced John Montague. His did a public reading of his poem ‘New Siege’ outside Armagh Jail in 1970 to support a jailed civil rights protestor, the nationalist Bernadette Devlin.

• As an adult he spent some time trying to recapture the American experience, a search reflected in some of his poems.

• Separation from his father all his life affected him emotionally as we read in his poem ‘The Cage’.

• The pain of rejection by his mother was even more traumatic for his personal development as we read in the poem ‘The Locket’.

• John Montague is renowned internationally as one of the major Irish poets of the twentieth century.

- Montague died at the age of 87 in Nice on 10 December 2016 after complications from a recent surgery. He is survived by his wife Elizabeth Wassell, daughters Oonagh and Sibyl and grandchildren Eve and Theo.

MAJOR THEMES IN MONTAGUE’S POETRY

Childhood: Like many poets on our course, Montague is fascinated with the subject of childhood. AWP describes the relative safety and comfort of a childhood in Ireland during the war. While the rest of Europe was plunged into destruction, Ireland remained safely on the ‘periphery of incident’. While young boys were fighting and dying all over Europe the young poet was free to ‘belt a football through the air’. Yet the ‘drama of unevent’ that constituted the war years in Ireland is briefly shattered for the poet when he encounters the newsreel of the death camps and discovers the grim reality of ‘total war’.

What might be described as a darker aspect of childhood is explored in LDRMC. There is a sense in this poem that the Irelands of Montague’s youth was a dark and haunted place, a land where ancient beliefs and superstitions still survived. We get a sense that during his childhood many people still believed in myths and magic, in ghosts, curses and supernatural demons; ‘Ancient Ireland, indeed! I was reared by her bedside, / The rune and the chant, evil eye and averted head/ Fomorian fierceness of family and local feud.’ For an imaginative child growing up in this society, it was easy to believe that magic still existed, that ancient monsters such as the Fomorians still roamed the land, in the dark countryside just beyond the reach of the farmhouse lights.

A similar theme is evident in TWDR where the poet describes his childhood terror of an old woman that lived in his locality. This poor and seemingly quite ugly old woman terrified the young poet with her ‘hooked nose’, her ragged clothes and the pack of dogs that always surrounded her. To him, she seemed a kind of witch, a terrifying supernatural figure who ‘haunted my childhood’. Yet while Montague’s poetry described this ‘Ancient Ireland’ it also records it’s passing away. As the country became more modern and Europeanised the old legends and superstitions no longer exerted the same power. As he grows up he can see the old legends and superstitions for what they were. This is particularly evident in TWDR where he realises that the ‘cailleach’ that so terrified him in his youth is only human after all and he ends up chatting to her by the roadside, reminiscing and gossiping ‘in ease’ about the people of the parish.

Violence: Montague’s work is haunted by the threat and the possibility of violence. This is particularly evident in ‘A Welcoming Party’ (AWP) where the young speaker is left greatly troubled by his encounter with images of the holocaust. He pulls no punches in his depiction of the horrors of war. His description of the holocaust victims here has been described as disgusting, bizarre and disturbing. Their mouths are described as ‘burnt gloves’, their bodies are depicted as nests full of insect eggs and their hands are depicted as begging bowls.

‘The Wild Dog Rose’ (TWDR), meanwhile, presents violence in an Irish context. The depiction of the attempted rape of the old woman is almost as shocking as that of the holocaust victims. The drunken labourer invades the old woman’s home whirling his boots in an attempt to ‘crush the skulls’ of her dogs. There is something truly horrific about the image of him wrestling her to the ground and ‘rummaging’ in her ‘tasteless trunk’ of a body. Yet this violent scene serves an important symbolic function, representing the violence and misery that had been visited upon Ireland over the centuries. The violation of the old woman echoes many ancient Irish songs and poems in which a woman, representing the land of Ireland, is violated by some ruthless villain who represents the foreign oppressor.

The hidden side of human personalities: John Montague contemplates the vulnerable underside of people who may appear harsh on the surface. ‘Maggie Owens… all I could find was her lonely need to deride’ [LDRMC] ‘Mary Moore… a by-word for fierceness… dreamed of gipsy love-rites’ [LDRMC] Montague also senses how a human hurt can deform a life. ‘the cailleach, that terrible figure who haunted my childhood but no longer harsh, a human being merely, hurt by event’ [TWDR] He reveals the real personality behind the public smiles of his father. ‘My father… extending his smile to all sides of the good (all white) neighbourhood… the least happy man I have known’ [TC] Montague is aware of the duality of our gestures in different contexts. An everyday movement of the hand in public, in traffic, that is mechanical in effect, can be deeply intimate in effect in the privacy of lovemaking, ‘changing gears with the same gesture as eased your snowbound heart and flesh’ [TSG]

John Montague is able to forgive his mother for rejecting him because he sees her pain and senses the different personality she had before her life turned harsh. ‘my double blunder… poverty… yarning of your wild young days… the belle of your small town… landed up mournful and chill’ [TL]

The impact of family on his life: As we have discovered, Montague’s family situation was far from ideal. Like thousands of Irish people, his parents were forced to emigrate to America where they struggled to survive in the face of extremely difficult circumstances. The consequences of this struggle are movingly portrayed in ‘The Cage’ (TC). The battle with poverty and the effort to make a home in a new society have clearly scarred the poet’s father who is described as ‘the least happy man I have known’. His deep unhappiness is evident in his alcoholism. Each night he is compelled to drink himself into oblivion as if only this will numb the pain of his existence, ‘the only element he felt at home in any longer: brute oblivion’.

Yet the poet’s mother, it seems, suffered even more. He claims that the brutal circumstances of her life – emigration, poverty, a loveless marriage – damaged her in some fundamental way, leaving her ‘wound’ in a ‘cocoon of pain’. She is unable to bond with her son and eventually sends him back to Ireland – causing great psychological damage to both herself and her son, so much so that in ‘The Locket’ (TL), he refers to her as a ‘fertile source of guilt and pain’.

The harshness of life: John Montague portrays the suffering of lonesome, impoverished locals from the hills around Garvaghey (Garbh Fhaiche = rough field = Garvahey). ‘When he died his cottage was robbed… driving cattle from a miry stable… forsaken by both creeds… Fomorian fierceness of family and local feud’ [LDRMC] He depicted the suffering of his father, a prisoner of poverty in New York. ‘ my father, the least happy man I have known…the lost years… released from his grille… drank neat whiskey until… brute oblivion.’ [TC] Montague spells out the extent of his mother’s physical pain and anguish. ‘ source of guilt and pain… the harsh logic of a forlorn woman’ [TL] He portrays the life-long loneliness and the brutal rape of a seventy-year-old spinster. ‘the cailleach… hurt by event… loneliness, the monotonous voice in the skull that never stops… he rummages while she battles for life bony fingers reaching desperately to push against his bull neck…’ [TWDR] Montague also portrays the horror of concentration camps. ‘From nests of bodies like hatching eggs flickered insectlike hands and legs’ [AWP]

A sense of place: Montague observes and draws the landscape of his childhood. ‘the cottage, circled by trees, weathered to admonitory shapes of desolation…where the dog rose shines in the hedge’ [TWDR] ‘a bend in the road which still shelters primroses’ [TC] ‘ a crumbling gatehouse. Famous as Pisa for its leaning gable’ [LDRMC] ‘From main road to lane to broken path’ [LDRMC] Montague pinpoints the essence of nature’s music as created by the wind in the Irish landscape. ‘seeping out of low bushes and grass, heatherbells and fern, wrinkling bog pools, scraping tree branches…’ [W] Montague evokes the horror of Auschwitz. ‘a welcoming party of almost shades… an ululation, terrible, shy’ [AWP] He also neatly depicts the irrelevance of Ireland geo-politically in the 1960s. ‘to be always at the periphery of incident’. He mentions what would strike an Irish visitor to New York. ‘listening to a subway shudder the earth.’ [TC] Montague sums up the essence of a Brooklyn neighbourhood. ‘(all-white) neighbourhood belled by St Theresa’s church.’ [TC] Montague evokes the intimacy of the marriage bedroom. ‘a secret room of golden light… healing light… gesture … eased your snowbound heart and flesh.’ [TSG]

Isolation and separation: Montague’s parents suffered separation and social isolation. ‘My father… brute oblivion’ [TC] Like his father, his mother suffered from self-imposed oblivion. ‘the harsh logic of a forlorn woman resigned to being alone’ [TL] Montague with great sympathy captures the reason for an odd old lady’s personality. ‘the only true madness is loneliness, the monotonous voice in the skull that never stops because never heard’ [TWDR] Her isolation means that she seeks no redress from the authorities for rape. She suffers with a stoicism born of a folk version of religion. ‘she tells me a story so terrible I try to push it away… I remember the Holy Mother of God and all she suffered.’ [TWDR] Montague captures the isolation of his scattered elderly rural neighbours. ‘Jamie McCrystal sang to himself… Maggie Owens… even in her bedroom, a she-goat cried… Billy Eagleson… forsaken by both creeds… ‘ [LDRMC]

Human love: Montague is quite famous within the literary world as a poet of love. Intense descriptions of erotic love, in particular, recur in many of his poems. We see this in ‘The Same Gesture’ (TSG) where the couple’s lovemaking is unashamedly celebrated: ‘It is what we always were- / most nakedly are’. Lovemaking is presented as something spiritual and holy. The couples’ hands moving on each other’s skin, we’re told, is like something from a religious ceremony: ‘the shifting of hands is a rite’. Love and sexual intimacy are depicted as having a powerful healing quality: ‘Such intimacy of hand / and mind is achieved / under its healing light’. Oneness is also celebrated, the notion that two lovers can somehow forget themselves and blend into one: ‘We barely know our / selves there.’

TSG, too, is intensely aware of the fragility of love. Emotional and sexual intimacy can be a spiritual and ‘healing’ thing. Yet a relationship can also become bitter and sour leading to hatred and even violence. The poem suggests that in this modern age love and intimacy are becoming more and more difficult to maintain. In this busy world where time and space are such a precious commodity, it can be easy to lose sight of what matters. The pressures of ‘work, phone, drive through late traffic’ must not cause us to neglect our relationships. Love, the poem implies, requires private space, a ‘secret room’ if it is to flourish if its ‘healing light’ is to shine. In the modern world, however, such space is increasingly difficult to come by.

Nature: As with other poets like Kavanagh and Frost, Montague’s work is regularly inspired by the natural world. This is very evident in ‘Windharp’ (W), in particular where he lovingly describes the Irish landscape with its ‘heather bells and fern, / wrinkling bog pools’. In this phrase we see Montague’s powers of description at their best: we can easily imagine the ripples on a bog pool resembling wrinkles on a piece of cloth.

A love of the Irish landscape is also evident in LDRMC with its celebration of the folk who live among the mountains and glens of rural County Tyrone. TWDR, too, displays the poet’s love of nature with its meticulous description of the tender wildflowers with their ‘crumbling yellow cup / and pale bleeding lips’. Yet the harsher aspects of nature are also lovingly rendered, such as the old woman’s rough field with its ‘rank thistles’ and ‘leathery bracken’. He observes nature’s beauty in eloquent language, ‘Gulping the mountain air with painful breath’ [LDRMC] ‘weathered to admonitory shapes of desolation by the mountain winds’ [TWDR]

Montague personifies the effects of climate on the Irish landscape as ‘ a hand ceaselessly combing and stroking the landscape’ [W]. He is also aware that not all that is beautiful is strong, ‘dog rose… at the tip of a slender, tangled, arching branch… weak flower, offering its crumbling yellow cup and pale bleeding lips fading to white’ [TWDR]

It is unsurprising, therefore, given Montague’s obvious love of the Irish landscape that he describes it as something ‘you never get away from’. Even when you leave the country, he claims, the sound of the wind through the Irish countryside, that ‘restless whispering’, will still somehow echo in your ears.

MAIN ELEMENTS OF MONTAGUE’S STYLE

Form John Montague is a lyric poet. He uses various stanza forms in the poems selected for the Leaving Certificate. He favours a poem of between four and seven stanzas with either six or seven lines per stanza. However, he deviates from this at times. He doesn’t tend to follow a definite rhyming pattern. Many of his poems have rhyme, though he is not strict about this. You are as likely to see half-rhyme as rhyme.

Speaker: In most of Montague’s poems the speaker is the poet himself. Most of his material comes from his lived experience and direct observations. He is a poet of the self, a romantic poet in that sense. He uses poetry to arrive at perceptions about his parents, partners, memories and the impact on him of national and international events.

Tone: Montague’s various tones range from pain to empathy, admiration and wonder. The word which applies to much of his poetry is compassionate. His tone is often one of intelligent detachment. At times he is capable of sarcasm. His tone can sometimes sound haunted, guilty even for the actions of others. He is capable of rueful and frustrated irony as illustrated in the final line of ‘A Welcoming Party’.

Language: Montague’s language is personal and anecdotal. He addresses the reader in conversational English. The need for rhythm and a regular beat may lead to the omission of obvious words or the changing of word order or phrase order. His most striking feature is his use of adjectives, sometimes in a group of three. It is worth commenting on his adjectives and how they convey meaning, express tone and achieve mood. ‘Windharp’ is a very eloquent poem in which to investigate the effect of adjectives. The fourth stanza of ‘The Wild Dog Rose’ is a powerful example of Montague’s talent for selecting adjectives.

Montague’s choice of verb is often apt and evocative. The use of the verb ‘rummages’ in its context in ‘The Wild Dog Rose’ is both horrifying and touching in its graphic violence. A clear example of Montague’s ability to use a pithy phrase is found in ‘A Welcoming Party’ when he refers to Ireland’s remoteness from what matters in the world at large: ‘to be always at the periphery of incident’. He defines the ‘Irish dimension’ of his childhood as ‘drama of unevent’. Montague matches language to meaning.

Imagery: As partly a narrative type of poet, many of Montague’s images are descriptions of actual memories, colourful pictures from his lived experience or the experience of others like Minnie Kearney narrated first to him and then to the reader as a third-person account. A particularly graphic example of the latter is found in ‘The Wild Dog Rose’. The poem contains an uncensored example of violence, a detail of which is the following: ‘the thin mongrels rushing out, but yelping as he whirls with his farm boots to crush their skulls’. The effect of the word ‘yelping’ on the reader is strong here. Consider the locket around his mother’s neck as a graphic image from his life.

Montague also chooses striking comparison images to convey his intelligent perceptions. The image of a cage for his father’s work booth is an example of Montague’s clear but intelligent metaphors. Likewise, his simile of the dolmen is profound and carries many resonances. The detailed image of the dog rose from the third section of ‘The Wild Dog Rose’ is an illustration of Montague’s descriptive powers and of his ability to use an actual image as a symbol of human fragility.

Verbal music: For Montague’s lyrical music you will find various sound repetitions, rhymes and half-rhymes, alliteration, assonance, onomatopoeia, consonance and sibilance in all his poems. For assonance listen to the ‘u’ sounds in ‘A Welcome Party’ especially in lines seven to ten. This enhances the effect of a group wail or lamentation as suggested by the word ‘ululation’.

A useful example of onomatopoeia is found in line two of ‘Windharp’, where the words imitate the breezes in the bushes and grass: ‘ the restless whispering’. This is a case of assonance ‘e’ and sibilance combining to create a musical effect that reinforces meaning.

For a more detailed illustration of verbal music examine the precise examples provided in the notes on three individual poems by John Montague in the Leaving Cert English Ordinary Section on Skoool.ie .

SAMPLE ANSWER: Give your personal response to the poetry of John Montague.

I am a big fan of John Montague because I find his poetry very emotional and moving. Much of this emotion comes from the depiction in his poems of human relationships. In poem after poem, he explores the difficulties that can exist in human relationships. Several of his poems reveal the tensions and difficulties that can dog even the most successful of romances. Family pressures, too, are movingly explored in these poems. Yet what I found most attractive about Montague’s work is its emphasis on the fact that these difficulties can be overcome or reconciled.

Montague is quite famous within the literary world as a poet of love. Intense descriptions of erotic love, in particular, recur in many of his poems. We see this in ‘The Same Gesture’ (TSG) where the couple’s lovemaking is unashamedly celebrated: ‘It is what we always were- / most nakedly are’. Lovemaking is presented as something spiritual and holy. The couples’ hands moving on each other’s skin, we’re told, is like something from a religious ceremony: ‘the shifting of hands is a rite’. Love and sexual intimacy are depicted as having a powerful healing quality: ‘Such intimacy of hand / and mind is achieved / under its healing light’. Oneness is also celebrated, the notion that two lovers can somehow forget themselves and blend into one: ‘We barely know our / selves there.’

In ‘The Same Gesture’, too, the poet is intensely aware of the fragility of love. Emotional and sexual intimacy can be a spiritual and ‘healing’ thing. Yet a relationship can also become bitter and sour leading to hatred and even violence. The poem suggests that in this modern age love and intimacy are becoming more and more difficult to maintain. In this busy world where time and space are such a precious commodity, it can be easy to lose sight of what matters. The pressures of ‘work, phone, drive through late traffic’ must not cause us to neglect our relationships. Love, the poem implies, requires private space, a ‘secret room’ if it is to flourish if its ‘healing light’ is to shine. In the modern world, however, such space is increasingly difficult to come by.

One of his most emotional poems is ‘The Locket’, where he describes his difficult relationship with his mother. He tells us that his mother has been a ‘fertile source of guilt and pain’ for him throughout his life. According to the poet, his mother regarded his birth as a ‘double blunder’. The first part of this ‘double blunder’ stemmed from the fact that the poet was born a boy when she really wanted a girl. Secondly, Montague was turned the wrong way in the womb, making the process of his birth extremely difficult for her. According to the poem, this ‘double blunder’ caused the mother to reject her son. She was never really affectionate to him and ‘sent him away’ when he was four years old. He was sent back to Ireland where he lived with his aunts.

It seems that even in later years the mother could not bear to be around her child. When she returned to Ireland she did not reclaim her son and instead went to live in a different village a few miles away from where he lived. As a young man Montague would ‘cycle down’ to visit her, but eventually, she told him to stop coming: ‘I start to get fond of you, John, / and then you are up and gone.’ I found this aspect of the poem extremely moving and felt very sorry for the young Montague. I felt he had done nothing to deserve this harsh treatment from his mother. After all, it was not his fault he was born ‘the wrong sex’ and the ‘wrong way round’. I found the mother’s behaviour somewhat cruel and felt that she had unfairly created feelings of ‘guilt and pain’ for her son.

‘The Cage’ also explores the poet’s feelings of ‘guilt and pain’ and in this case, the negative emotions stem from his difficult relationship with his father. He describes his father as the ‘least happy man I have known’. This unhappy man spent his days working in the dark and noise of the New York subway: ‘listening to a subway shudder the earth’. He was an alcoholic who would drink himself into ‘brute oblivion’. Only when obviously drunk was he in any way happy. According to the poem, this was the ‘only element / he felt at home in any longer.’

One of the most moving aspects of Montague’s poetry is his depiction of his reconciliation with his parents. When his mother dies he discovers that she loved him after all and that for years she had worn a locket that contained his picture: ‘an oval locket / with an old picture in it, / of a child in Brooklyn’. Similarly, the poet eventually comes to terms with his troubled father and they walk ‘together / across fields of Garvaghey / to see hawthorn on the Summer / hedges’. I found it very tragic, however, that both reconciliations came too late. For the poet’s mother was unable to express her love for him while she was alive and it is only after her death that he learns of it. The poet’s reconciliation with his father also comes too late. For no sooner has the father returned to Ireland and spent some time with his son than the son himself must depart: ‘when wary Odysseus returns / Telemachus should leave’. The poet seems to be forever haunted by this unhappy man and his failure to ever really connect with him and still sees his father’s ‘bald head’ when he descends into subway stations.

Another poem that showcases reconciliation is ‘The Wild Dog Rose’. As a child, the poet was terrified by the old woman who lived near his house, imagining her to be a terrifying witch with a ‘great hooked nose’, her ‘mottled claws’ and her eyes that were ‘ staring blue’ and ‘sunken’. I really like the way Montague captures the feelings of mystery and terror the boy experiences at the sight of this weird old lady who ‘haunted my childhood’. As in ‘The Cage’ and ‘The Locket’ there is a focus on reconciliation in this poem when Montague comes back as a fully grown young man to visit the ‘cailleach’. Now his feelings of ‘awe’ and ‘terror’ have been replaced by ‘friendliness’. The poet and the old woman stand by the roadside talking about old times: ‘we talk in ease at last, / like old friends’. Gradually he is reconciled with this old woman that scared him so much: ‘memories have wrought reconciliation between us’.

To sum up, then, the main reason I like Montague’s poetry so much is the convincing way in which it reveals human emotions. The poems very movingly portray negative emotions such as pain, guilt, fear and sorrow. Yet they also show how these negative emotions can be healed and overcome through a process of reconciliation. I find these aspects of his work very moving indeed.

JOHN MONTAGUE – SOME GRACE NOTES…..

“The only thing unchanging in life is change.”

- John Montague is a poet of emotion and of place. Memory, love, Ireland and elsewhere play a significant part in his work. The seven poems highlighted here tell of his fascination with his sense of his past and native place (LDRMC); his father (TC); his mother (TL); an old woman in his native place who tells him of an attempted rape (TWDR); Ireland’s landscape (WH); the complexities of love (TSG); and his awakening boyhood consciousness (AWP). According to Montague ‘the only thing unchanging in life is change’ (and a very eminent English teacher constantly reminded his class that ‘the only people who welcome change are babies with wet nappies’!) and his poetry is a chronicle of that change in his own life.

- The poems we have studied chart Montague’s boyhood, schooldays, early love, and relationships. Unhappiness and hurt feature in many of his poems. He speaks of himself as ‘An unwanted child, a primal hurt’ and admits that ‘my work is riddled with human pain’. However, he also writes tenderly and sensitively about landscape and love. He sees himself as the first poet of Ulster Catholic background since the Gaelic poets of the eighteenth century.

- Critic, Peter Sirr, describes Montague as ‘Public and private, internationalist and intensely focused on Ireland’. He says that Montague’s poetry results from ‘a complex and troubled journey’ and his poetry is ‘haunted, edgy and constantly in search of framing structures to make sense of its different worlds.’ That complex and troubled journey began in Brooklyn and moved through Ireland, North and South, later France and America, before returning to Cork and West Cork. Family and personal history and Ireland’s history became subject matter for the poetry and his poetic techniques were influenced not only by Irish but by French and American poetry.

- In an 1988 interview with Dennis O’Driscoll, Montague compared the making of poems to fishing, ‘trying to get the fish out on to the bank’ and he likened the making of poems to the dropping of a rose petal into the Grand Canyon. Many of his poems are intensely personal. He shares with us his understanding of intimate, private things and he also writes of life’s harshness and disappointments.

- Frost will always be associated with Vermont and Kavanagh will always be associated with Inniskeen and indeed, Montague will likewise always be associated with Garvahey (from the Irish ‘garbh fhaiche’ meaning ‘rough field’). It was his adopted place and he has made this place his own. ‘Among the welter of the world’s voices,’ he says, ‘in the streets, on the airwaves, in the press, you find your own voice, yet this does not isolate you, but restores you in your people. Across the world the unit of the parish is being broken down by global forces, and from Inniskeen to Garvahey, from Bellaghey to Ballydehob, to the Great Plains of America, an older lifestyle, based on the seasons, is being destroyed. But it can still be held in the heart and in the head.’

- In his Inaugural Lecture of the Irish Chair of Poetry on 14 May 1998, John Montague said: ‘So you wander round the world to discover the self you were born with’ and in that same lecture he agrees with Frank O’Connor who ‘argues that the strength of the storyteller often comes from the pressure behind him of a community which has not achieved definition, a submerged population’.

- In Peter Sirr’s words: ‘The need to unify the different levels of experience, the recognition that the personal and the political are necessarily meshed, are part of what makes Montague valuable’ and Montague identifies Ireland’s ‘three great losses in the nineteenth century’ as defining: ‘First the loss of people. Ireland had 8 million people in 1840. A third of those died or left. Second, the loss of the Irish language. Those who remained had to learn to speak English and it happened in ten years. Third, the loss of the music. Those who played music at the crossroads were driven out to America and there was fifty years of silence.’

Though his poetry contains striking and memorable images of scars and wounds, ‘I think the ultimate function of the poet is to praise’, says Montague.

You must be logged in to post a comment.