The Theme of Pride

In Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen looks at people who are guilty of pride, and the effects it has both on their lives and the lives of others. Everyone in the book has some degree of pride, but the key characters are often caricatures of proud people: Mr Collins and Lady Catherine de Bourg. Darcy and Elizabeth develop as characters during the course of the novel and they are also seen to have pride as part of their personality.

Caricatured pride is shown by Austen to be obnoxious. Lady Catherine is proud because she was born an aristocrat, raised to believe herself to be superior to others. She is patronising, believes she has a right to know and judge everything and gives petty advice because she needs to feel useful. She always likes to be the centre of attention, and she expects to be always obeyed.

Lady Catherine is challenged by Elizabeth, who unlike everyone else, is not overawed by her. Lady Catherine is outraged when Elizabeth answers her back at Rosings and later when she barges in to Longbourn. She tries to bully her at first, ordering her not to marry Darcy and finally insulting her by saying that accepting Darcy will pollute the shades of Pemberley. She demands instant submission and when this is not on offer her pride is severely dented.

Mr Collins had long been supplying this need. He had been raised with ‘humility of manner’, but living at Hunsford has made him a mixture of ‘pride and obsequiousness, self-importance and humility’ and this lapdog servility makes him even more unlikeable in our eyes. The key scene showing Collins’s pride comes with his proposal to Elizabeth, where he not only assures her he will not despise her for being without a dowry but tells her that she might as well accept him, for he is the best she can expect.

Elizabeth herself, though chiefly signifying prejudice, is guilty of the pride on which this prejudice is based. Darcy tells her when he proposes, ‘Had not you heart been hurt … (my faults) might have been overlooked’, and in the key chapter that follows, she admits this. She has been convinced she was right about Bingley’s treatment of Jane, Charlotte’s and Collins’s marriage, Wickham’s goodness and Darcy’s lack of worth. She learns that her prejudice has been due to her belief in the infallibility of her own judgement. Also, she realises her vanity has been wounded.

The distinction between pride and vanity is made early in the novel. Mary comments that ‘pride relates more to our opinion of ourselves, vanity to what we would have others think of us’. As well as pride, Elizabeth has, therefore, been guilty of vanity. She has been far too influenced by Wickham’s attention and Darcy’s neglect. She admits this immediately, making an honest effort from then on to be neither proud nor vain.

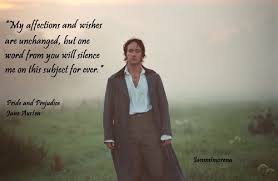

The chief representative of pride in the novel is Darcy. On his introduction in Chapter 3, he is said to be proud. He seems withdrawn, superior and cynical. He puts Elizabeth down coldly with a patronising comment about her looks. Later, despite his infatuation, he feels himself superior to Elizabeth and kindly condescends to ignore her towards the end of her visit to Netherfield so that ‘nothing could elevate her with the hope’ of marrying above herself. Pride convinces Darcy he is right to interfere in Bingley’s relationship with Jane, and pride keeps him from lowering himself and his family by disclosing Wickham’s bad nature.

By the time he makes his first blighted proposal to Elizabeth, Darcy is firmly established in our minds as the epitome of pride. The proposal, ‘not more eloquent on the subject of tenderness than of pride’, reveals a Darcy who considers he is doing her a favour. She is outraged and accuses him of ‘arrogance’ and ‘conceit’. Were he a lesser character, like Mr Collins, for instance, he would have sulked and moved on to fresher pastures, but Darcy, the hero, ponders Elizabeth’s accusations, realises the truth in them and he resolves to change. At first, we only see his outward transformation, his gentle behaviour at Pemberley, his assistance to the Bennets after the elopement. It is only after his second and more successful proposal that we see evidence of his complete change of heart. Loving Elizabeth has made him realise that people can be good despite their humble origins and that love is not compatible with condescension.

We must remember of course that Darcy was never all bad. Our view of him as such is largely formed by Elizabeth’s prejudice. His reputation for being proud largely stems from his being shy and his dislike of socialising. He may put people down, but he also helps them, as friends and dependants. Remember his housekeeper’s kindly comments: ‘Some people call him proud; but I am sure I never saw any thing of it’.

By the end of the novel, Darcy still has some pride, but with good reason. The mature Elizabeth has learnt, as have we, that there is good pride and bad. ‘Vanity is a weakness’, says Darcy, but with ‘superiority of mind, pride will always be under good regulation’. Elizabeth, thinking he is guilty of both, smiles. But Darcy is right. Vanity, as seen in Lady Catherine, Mr Collins, Elizabeth, and even in Darcy himself, is wrong, but pride, while also being wrong, can be acceptable if properly controlled. In many ways, Darcy controls his pride. The Darcy who saves Lydia and marries Elizabeth is a well balanced mature individual. He is master of Pemberley and Elizabeth sees this in a positive light; he has many good attributes and a capacity to help his family, tenants and friends. She defends Darcy to her father, telling him that he is proud, but has ‘no improper pride’.

Lady Catherine and Mr Collins don’t change in the course of the novel but Elizabeth and Darcy do. Having learnt a valuable lesson they both are now ready to take up residence at Pemberley and reign supreme at the centre of Austen’s universe!

THE THEME OF PREJUDICE

In this age of political correctness and media spin the notion of prejudice, as described in the novel, is very pertinent. In the novel, Jane Austen talks about the idea of ‘universal acknowledgement’, where society in general takes a united (and she infers, a biased) stand, welcoming Bingley because he is an eligible bachelor, rejecting Darcy because he seems proud and favouring Wickham because he flatters and charms.

Against this background of public prejudice, Jane Austen presents several particular illustrations of people who confuse appearance with reality because of their personal bias.

Mrs Bennet is probably the most humorous example of this, seeing the world in terms of the wealth and charm of potential husbands. Thus, she is blind to Collins’s faults, is deceived by Wickham, and yet cannot see Darcy’s real worth: ‘I hate the very sight of him’. (Yet, worryingly, she welcomes Wickham as Lydia’s husband even though he nearly ruined her reputation and the reputation of her family).

There are many examples of social prejudice and snobbery dealt with in the novel (and this overlaps with the vice of pride). Lady Catherine, Collins and the Bingley sisters all fail to see the real Bennets when they judge them early on. Look at Collins’s proposal and how he constantly reminds Elizabeth of her inferior position in life, echoing the comments of Lady Catherine at Rosings. The Bingley sisters spend several sessions judging Jane and Elizabeth on their relatives and their wealth.

Darcy, though in the main clear-sighted and intelligent in his approach to life, at first joins in this social snobbery. His initial opinion of Elizabeth herself was formed by her lack of beauty and then compounded by her lack of connections. This snobbery led him to influence Bingley away from Jane and to resist his own infatuation for Elizabeth. It is only when Elizabeth points out his pride, after his first proposal to her, that he realises his mistake and he makes an honest effort to change his behaviour. By the end of the novel, he respects Elizabeth’s family and sees only the true Elizabeth, not her social standing.

It is Elizabeth who most typifies prejudice for us. The first time she and Darcy meet he snubs her and this turns her against him. From then on, instead of attempting to understand him, she reacts only to his proud outer appearance and delights in fuelling her prejudice as much as possible. At first, she can be pardoned for disliking a man who has insulted her but, as she admits, her reasons were not sound. She wanted to score points, to seem clever, and to say something witty.

It is not until the first proposal that Elizabeth begins to doubt her judgement. After all, she has been prejudiced against Darcy because of his insensitive remarks and in the case of Wickham, her judgement has been clouded by sexual attraction and flattery. In the crucial Chapter 36, Elizabeth considers Darcy’s letter and there follows a careful account of how she overcomes her prejudice. At first totally biased against Darcy, without ‘any wish of doing him justice’, she then realises that if his account is true, she must have deceived herself. Notice how by putting the letter away she literally refuses to see the truth. Almost immediately, however, her strength of character triumphs, she rereads the letter, and Elizabeth now sees the situation clearly. She admits to being ‘blind, partial, prejudiced’ and achieves insight into the situation and her own character. She admits her fault to Jane, and by letting Wickham know that she sees the difference between appearance and reality, she makes a public statement of her new self-knowledge.

She sees things in a clearer light from this point on, viewing Pemberley with unbiased eyes and meeting Darcy with an open mind. She also begins to understand his criticisms of her family, seeing them objectively possibly for the first time in her life. Finally, she comes to accept Darcy as an acceptable partner and she works hard to overcome her family’s prejudices against him by presenting him in his true light.

Elizabeth has learnt many valuable lessons at the end of this novel: she now knows that ‘first impressions’ are rarely sufficient and she comes to see the reality of true worth, not the appearance of it. There may be lessons here for us as well. Our age is obsessed with image, and spin and outward appearances and social snobbery. Finding our own Elizabeth or Mr Darcy is not going to be easy either!

You must be logged in to post a comment.