The Last Vision of Eoghan Rua Ó Súilleabháin

The cow of morning spurted Do thál bó na maidine

milk-mist on each glen ceo bainne ar gach gleann

and the noise of feet came is tháinig glór cos anall

from the hills’ white sides ó shleasa bána na mbeann.

I saw like phantoms Chonaic mé, mar scáileanna,

my fellow-workers mo spailpíní fánacha,

and instead of spades and shovels is in ionad sleán nó rámhainn acu

they had roses on their shoulders. bhí rós ar ghualainn chách.

Translated by Michael Hartnett from his original Irish poem.

Commentary

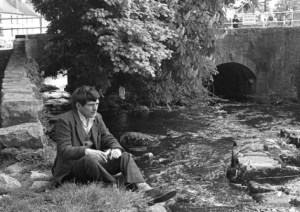

This gem of a poem was first published as part of Hartnett’s first collection in Irish, Adharca Broic, in 1978. The poem also appears in Hartnett’s 1987 collection, A Necklace of Wrens, with an English translation by the poet himself. Of the twenty-three poems in A Necklace of Wrens, thirteen are included from that first collection in Irish, Adharca Broic, with English translations by the poet. Peter Fallon, his publisher and editor, has stated that the poems included in A Necklace of Wrens were the only Irish poems that Hartnett wanted to be preserved after his ten-year sojourn in West Limerick. This collection was followed a year later by Poems to Younger Women, entirely in English. Theo Dorgan tells us that both these collections show ‘a startling return to the power and complexity we might have expected had the poet not turned aside from English in 1975’.

‘The Last Vision of Eoghan Rua Ó Súilleabháin’ offers a modern perspective on the traditional Aisling (vision) poem genre. The poem blends traditional imagery with contemporary twentieth-century realism, transforming the spectral ‘fellow-workers’, the ‘spailpíní fánacha’ of the original, into figures with ‘roses on their shoulders’ instead of spades, suggesting a hopeful, transformed vision of labour and society, rather than the lament for lost Gaelic order typical of historical Aisling poems.

Here, the focus shifts from the old political lament of older Aisling poems to a more modern, grounded, hopeful vision, using the image of the rose, the international symbol of the Labour Movement, of which Hartnett was a card-carrying member. While the original poems lamented historical events like the Flight of the Earls and the hoped-for return of Bonny Prince Charlie and the Stuarts to power, Hartnett’s poem shifts the focus to a contemporary sense of disillusionment and emotional turmoil. Hartnett does use the image of a new day dawning to reinforce the hopeful possibility of better days ahead, however, while Hartnett’s translation adapts the ancient Aisling form in a contemporary context, in my view, this Aisling is heavily laden with irony, if not cynicism, because of Labour’s perceived inability to improve the lot of the working class and its failure to gain long-term popular mainstream support, particularly in the post-World War II era.

The title and the poem itself reference the Aisling genre, a poetic form that developed in Gaelic poetry in the 17th and 18th centuries. Readers familiar with Irish poetry will also be aware that in these old Aisling poems, Ireland was often depicted as a woman: sometimes young and beautiful, sometimes old and haggard. In the final poem in his first collection in Irish, Adharca Broic, Hartnett reprints his iconic poem, Cúlú Íde, in which he portrays Íde (Ita Cagney in the English version) as a strong, formidable woman, and he endows her with many of the traditional characteristics of the spéirbhéan (the spirit woman) from the original Aisling poems. She is depicted as a modern Bean Dubh an Ghleanna, Gráinne Mhaol, Roisín Dubh or Caithleen Ní Houlihan – in effect, a symbolic representation of the new Ireland.

This modern Aisling, ‘The Last Vision of Eoghan Rua Ó Súilleabháin’ also features striking imagery, such as the ‘cow of morning’ that ‘spurted milk-mist on each glen’. The image of the cow, the Droimeann Donn Dílis, was also a stock reference to represent Ireland in Jacobite poetry and the hoped-for return of the Stuart dynasty, which, many at the time believed, would benefit Ireland. This initial image creates a surreal and elemental atmosphere, setting a new tone for the vision. The crucial shift occurs when these workers have ‘roses on their shoulders’ instead of ‘spades and shovels,’ symbolising a transformed, idealised vision of labour, where it is no longer depicted as hardship or indentured slavery but as something beautiful and dignified.

The rose, particularly the red rose, later became a symbol for the Labour Movement through the slogan ‘bread and roses,’ which represents the dual desire for both the means to live (bread) and a life of dignity and fulfilment (roses). This symbol is associated with the fight for social and economic justice and is used by many social democratic and labour parties, such as the Labour Party in Ireland and the UK.

The ‘phantoms’ seen by the speaker are described as ‘fellow-workers’, ‘comrades’ even, transforming traditional imagery of spectral figures into more tangible, relatable characters associated with Labour. The older, traditional variety are the sad spectral figures that accost Hartnett one summer’s evening as he heads from his home in Newcastle West to meet his uncle Dinny Halpin in Camas. The episode is recounted for us in the second section of his iconic poem, ‘A Farewell to English’,

These old men walked on the summer road

sugán belts and long black coats

with big ashplants and half-sacks

of rags and bacon on their backs.

These spectral figures were a pathetic vision, ‘hungry, snotnosed, half-drunk’. These ragged poets, Andrias Mac Craith, also known as An Mangaire Súgach, The Merry Peddlar, (along with his contemporary, Sean Ó Tuama an Ghrinn, who also hailed from Croom, the seat of one of the last ‘courts’ of Gaelic poetry), Aodhagán Ó Rathaille from Meentogues near Rathmore in the Sliabh Luachra area (also the birthplace of Eoghan Rua Ó Súilleabháin), and Dáithí Ó Bruadair, who was on his way from Springfield Castle, the seat of the Fitzgeralds, to Cahirmoyle, the seat of his other great patron, John Bourke), represented the sad remnants of a glorious past.

The ‘phantom’ figures leave Hartnett resting ‘on a gentle bench of grass’, leaving him to ponder his own future as their direct descendant:

They looked back once,

black moons of misery

sickling their eye-sockets,

a thousand years of history

in their pockets.

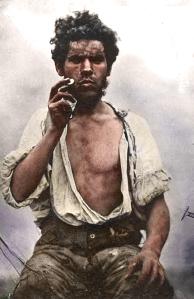

Eoghan Rua Ó Súilleabháin, the putative author of this Aisling and a real-life spailpín in his own right, lived a life which was the stuff of legend and lore, and, indeed, it has many similarities with Hartnett’s own rakish life. Many of the stories surrounding him may very well be apocryphal, to say the least. However, he and his fellow parishioner, Aodhagán Ó Rathaille, are most famous for their mastery of the Aisling genre.

Eoghan Rua was born in 1748 in Meentogues, in the mountainous Sliabh Luachra area, in southwestern Ireland. By the time of his birth, most of the native Irish in the southwest had been reduced to landless poverty. However, the area boasted of having one of the last ‘classical schools’ of Irish poetry, descended from the ancient, rigorous schools that had trained bards and poets for generations. In these last few remnants of the bardic schools, Irish poets competed for attention and rewards, and learned music, English, Latin and Greek.

Eoghan Rua (the Rua refers to his red hair) was witty and charming but had the misfortune to live at a time when an Irish Catholic had no professional future in his own country because of the anti-Catholic Penal Laws. He also had a reckless character and threw away the few opportunities he was given. For example, at the age of eighteen, he opened his own school; however, we are told that ‘an incident occurred, nothing to his credit, which led to the break-up of his establishment.’

Eoghan Rua then became a spailpín, an itinerant farm worker, until he was 31 years old. He was then conscripted into the British Navy under interesting circumstances. Ó Súilleabháin was then working for the Nagles, a wealthy Anglo-Irish family. They were Catholic and Irish-speaking, and had their seat in Kilavullen along the Blackwater valley near Fermoy, County Cork. (The Nagles were themselves an unusual family. The mother of the Anglo-Irish politician Edmund Burke was one of the Nagles, as was Nano Nagle, the founder of the charitable Presentation order of nuns. She was declared venerable in the Catholic Church on 31 October 2013 by Pope Francis).

Daniel Corkery relates that, ‘I have had it told to myself that one day in their farmyard Eoghan Rua heard a woman, another farm-hand, complain that she had need to write a letter to the master of the house, and had failed to find anyone able to do so. ‘I can do that for you’, Eoghan said, and though doubtful, she consented that he should. Pen and paper were brought to him, and he sat down and wrote the letter in four languages: in Greek, in Latin, in English, and in Irish. ‘Who wrote this letter?’ the master asked the woman in astonishment. The red-headed young labourer was brought before him, questioned, and thereupon set to teach the children of the house. However, again owing to Eoghan Rua’s bad behaviour, he had to flee the house, the master pursuing him with a gun’. Legend says he was forced to flee when he got a woman pregnant: some say that it was Mrs Nagle herself!

Ó Súilleabháin escaped to the British Army barracks in Fermoy, and he soon found himself aboard a Royal Navy ship in the West Indies, ‘one of those thousands of barbarously mistreated seamen’. He sailed under Admiral Sir George Rodney and took part in the famous 1782 sea Battle of the Saintes against French Admiral Comte de Grasse. The British won, and to ingratiate himself with the Admiral, Ó Súilleabháin wrote an English-language poem, Rodney’s Glory, lauding the Admiral’s prowess in battle and presented it to him. Ó Súilleabháin asked to be set free from service, but this request was denied him.

Much of Eoghan Rua’s life is unknown and clouded in mystery and intrigue. He returned after his wartime exploits to his native Sliabh Luachra and opened a school again. Soon afterwards, at 35, he died from a fever that set in after he was struck by a pair of fire tongs in an alehouse quarrel by the servant of a local Anglo-Irish family. ‘The story of how, after the fracas in Knocknagree in which he was killed, a young woman lay down with him and tempted him to make sure he was really dead, was passed on with relish’.

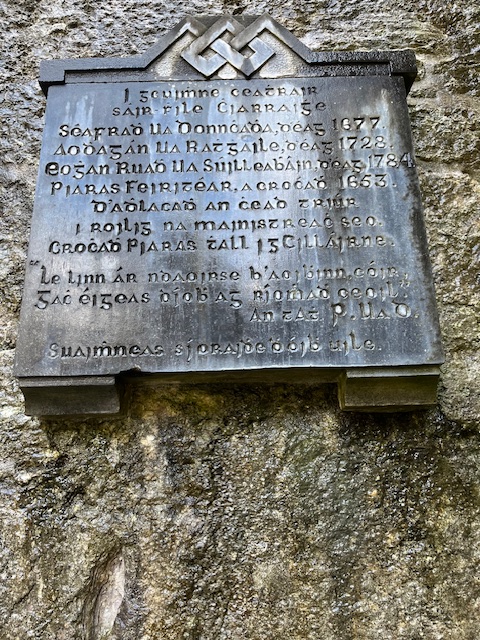

There is some confusion as to where he is buried. Some claim he was buried in midsummer 1784, in Nohoval Daly graveyard (or Nohoval Lower Graveyard), which is located on the Cork side of the River Blackwater on the R582 Knocknagree to Rathmore road. Others claim that he was buried in the cemetery of Muckross Abbey, Killarney, along with two other great Kerry poets, Séafradh Ua Donnchadha, who died in 1677, and Aodhagán Ó Rathaille, who died in 1728. There is a plaque on the wall of Muckross Abbey today that commemorates this event. The plaque also pays tribute to another great Kerry poet, Piaras Feiritéar, who was hanged ‘thall i gCill Áirne’, ‘over in Killarney’, in 1653. The plaque also has an inscription which is attributed to an tAthair Pádraig Ó Duinnín, the great lexicographer, most famous for compiling the Foclóir Gaeilge–Béarla (Irish-English Dictionary), first published in 1904. He, too, was from Meentogues, the birthplace of both Ó Suilleabhán and Ó Rathaille.

It was said of Eoghan Rua that,

Perhaps there never was a poet so entirely popular– never one of whom it could be more justly said volitar vivus per ora virum [He soars, alive in the mouths of the people]. His songs were sung everywhere…. Munster was spellbound for generations…. The present generation, to whom the Irish language is not vernacular, in reading these poems should bear in mind that they were all intended to be sung, and to airs then perfectly understood by the people, and that no adequate idea can be informed of their power over the Irish mind, unless they are heard sung by an Irish-speaking singer to whom they are familiar.

There is much to admire in this short poem. Indeed, I feel I am but scratching the surface. However, short and concise as it is, I feel it has relevance to a modern audience eager to bridge the gap to a harrowing era in Irish literary history. Indeed, the poem’s tone is one of elegy, lament, and perhaps a quiet resignation to loss, reflecting the disorienting experience of a changing world.

In his wide-ranging essay, which gives an overview of Hartnett’s work, ‘A Singular Life: The Poet Michael Hartnett’, Theo Dorgan points out that although he never translated the totem figures, Mac Craith and Ó Tuama,

‘he could and did think of himself as the favoured inheritor of a tradition, and also as one obliged to be loyal to that tradition. This sense of obligation would become the sign and signature of his work’.

That life’s work in both languages serves as a bridge between Ireland’s rich poetic past and its modern present. His poetry and translations from the Irish have given him firsthand knowledge of traditional Irish forms, such as the Aisling, and he uses these in very innovative ways in his contemporary poetry. By taking a traditional form such as the Aisling and imbuing it with modern themes, Hartnett allows a new generation to connect with a classical poetic tradition while grappling with the emotional and political undercurrents of their own time.

The startling achievement of this short eight-line poem is that Hartnett manages to crystallise all the tropes and traditions of the Aisling genre while at the same time staying relevant to a modern audience. This Aisling alone proves that he is a worthy successor to the ‘phantoms’, those spectral figures who confronted him at Doody’s Cross, ‘a thousand years of history in their pockets’.

References

Dorgan, Theo. ‘A Singular Life: The Poet Michael Hartnett’, from The Poets and Poetry of Munster: One Hundred Years of Poetry from South Western Ireland, ed. Clíona Ní Ríordáin and Stephanie Schwerter (December 2022/January 2023).

Hartnett, Michael. Adharca Broic, Loughcrew: Gallery Press, 1978.

Hartnett, Michael. A Necklace of Wrens: Poems in Irish and English, editor Peter Fallon, Loughcrew: Gallery Press, 1987.

Hartnett, Michael. Poems to Younger Women, Loughcrew: Gallery Press, 1988.

You must be logged in to post a comment.