Abstract: Where did Michael Hartnett get the inspiration for the title of his collection, A Farewell to English? We believe that Aindrias Mac Craith’s most iconic song, Slán le Máighe (Farewell to the Maigue), was an influence and reference point for Hartnett’s ‘Farewell’, as well as being the inspiration for both the naming of the title poem of Hartnett’s collection, A Farewell to English, and, indeed, the naming of the collection itself.

A Christmas Collaboration: Vincent Hanley and Don Hanley

Michael Hartnett’s A Farewell to English caused quite a stir in literary circles back in 1975. It was seen by some as a bold change of direction for Hartnett, by then an established poet in the Irish literary scene and equally it was seen by others as a self-inflicted literary act of seppuku or self-immolation. Famously (infamously!) on June 4th, 1974, Hartnett had walked onto the stage of the Peacock Theatre in Dublin, at an event organised by the Goldsmith Press, and made one of the most intriguing, quixotic statements ever made by an established Irish poet. At that event, Michael Hartnett informed the audience of his resolution to cease writing and publishing in English and, from then on, to write and publish solely in Irish. He said his ‘road towards Gaelic’ had ‘been long and haphazard’ and until then ‘a road travelled without purpose’ but reassured his audience that he had realised and come to terms with his identity while acknowledging that his ‘going into Gaelic simplified things’ for him and provided answers which some considered to be naive but at least gave him ‘somewhere to stand’ (Walsh, 7). The statement was received largely negatively by critics and contemporaries, at best a bizarre misstep soon to be forgotten, at worst an ideologically motivated rebuke to the Irish poets writing in English at the time.

This dramatic ‘Farewell’ has always been somewhat problematic. Many of his detractors at the time expected him, once he had made this momentous decision, to stick rigidly to his promise as if it had been set in stone. Inevitably, they criticised him and chided him when his ambitious project seemed to peter out in the mid-80s. Perhaps this reaction can be seen as an effort by his critics to finally ‘pigeonhole’ the poet and hold him accountable. However, Michael Hartnett’s variety as a poet – balladeer, satirist, love poet, translator, poet in Irish as well as English, and his complicated bibliography, with numerous compilations, collections and selections, as well as individual volumes from several different publishers, always had the effect of obscuring his achievement or hiding its core elements.

An artist moves from obsession to obsession, from one project to another, and nothing is ever set in stone; ‘Farewells’ are never ‘Adieu’, more ‘Au Revoir’; new beginnings are inevitable. Hartnett was no different; he shifted from English to Irish and back again, he moved from city to country and back again; from the hillside in Glendarragh to Emmett Road in Inchicore, where, for good measure, he composed an extended haiku sequence in English. As Peter Sirr points out, this is the ‘kind of creative restlessness that fed Hartnett as a poet but that sometimes made critics scratch their heads’ (Sirr, 294). That said, when assessing Hartnett’s ‘Farewell’, we think it is fair to say it is best realised by the poems and ballads themselves (both in English and Irish), which more fully express the motivating poetic philosophy which led to the theatrical stunt on the Peacock stage, rather than the stunt itself!

To appraise the decision to bid a farewell to English, therefore, we must look to the collection and the title poem of the collection. If the concluding poem for which the collection is named is to be read as explanation, as well as a statement of intent, it is not a disillusionment with language, but rather with the use of that language in Ireland, and the cultural significance which that use carries. Hartnett’s decision, and the poem itself, are loaded with inferences within a political and postcolonial context. The poem’s significance, however, lies in the fact that it is not a poem against a language, but the political and dogmatic meanings which we have attached to that language.

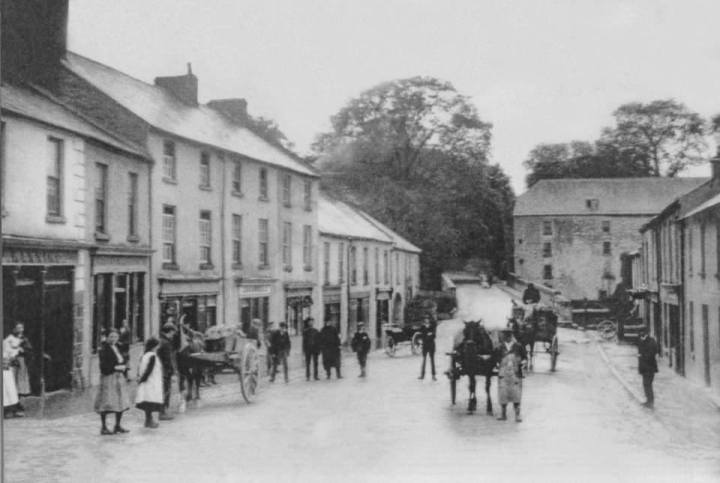

His poem, ‘A Visit to Croom, 1745’, appears in that 1975 edition of A Farewell to English and is placed immediately before the title poem in the collection. The poem consists of strikingly vivid imagery and there are a myriad of great historical undertones present; echoes of Séan Ó Tuama’s inn, with its bardic school of poetry is conveyed in bold, flamboyant brush strokes; echoes too of great battles, the Boyne, Athlone, Aughrim, the Siege of Limerick, the ill-fated Treaty of Limerick, Sarsfield and The Wild Geese. In the poem Hartnett, the travelling spailpín, places himself back in Croom, probably in Ó Tuama’s hostelry, on his lonely journey back into the Gaelic tradition. He has trudged fourteen miles, in the shoes of those phantoms he visualises at Doody’s Cross, ‘in straw-roped overcoat’ to get here and all for nothing. ‘Five Gaelic faces’ greet him, and all he can hear is ‘a Gaelic court talk broken English of an English king’. His anger and disappointment are palpable,

It was a long way

to come for nothing.

Then the opening scene in ‘A Farewell to English’ takes place in yet another hostelry, Windle’s Pub in Glensharrold, Carrickerry, a few miles outside Newcastle West, where he introduces us to the raven-haired barmaid, Mary Donovan, who spurs him to verse, ‘her mountainy body tripped the gentle / mechanism of verse’ (Collected Poems, 141). This imagined segment of the poem is used as a device through which Hartnett comments upon his poetic inspiration and process, as well as his relationship with the Irish language: ‘the minute interlock / of word and word began, the rhythm formed’ (Collected Poems, 141). The weight which the poet gives to ideas of tradition within his creative process is clear here, suggesting the importance which ideas of authenticity play. Such shibboleths are never treated as unassailable, however, but rather made tangible through tactile imagery of sinking into, and sifting through, the morass of tradition: ‘I sunk my hands into tradition / sifting the centuries for words’ (Collected Poems, 141). However, because of his somewhat faltering Irish, he is forced to resort to age-old cliches to describe the barmaid using well-worn semi-classical phrases, ‘mánla, séimh, dubhfholtach, álainn, caoin’. Harnett then rebukes himself for doing so – ‘What was I doing with these foreign words?’ (Collected Poems, 141). His project, his new direction, is to find a new poetic voice in Irish, not to rehash old clichés, and by doing so, come to Irish not as a ‘foreigner’ but as a fellow of Aindrias Mac Craith and the Maigue poets and in doing so, make his own contribution to the bardic tradition that has inspired him.

Then in the second section, he describes an encounter on the road which hovers somewhere between reality and dream, aisling (the Irish word for a vision) or epiphany. The incident takes place at Doody’s Cross as the poet walks out one summer Sunday evening from Newcastle West to the cottage in Camas. He is on his way to meet up with his uncle, Dinny Halpin. He sits down ‘on a gentle bench of grass’ to rest his weary feet after his exertions when he sees approaching him three spectral figures from the Bardic Gaelic past – Andrias Mac Craith, Aodhagán Ó Rathaille, and Daíbhí Ó Bruadair. These ‘old men’ walked on ‘the summer road’ with

sugán belts and long black coats

with big ashplants and half-sacks

of rags and bacon on their backs.

They pose as a rather pathetic group, ‘hungry, snot-nosed, half-drunk’ and they give him a withering glance before they take their separate ways to Croom, Meentogues and Cahirmoyle, the locations of their patronage, ‘a thousand years of history / in their pockets’. Here, Hartnett is situating himself as their direct descendant and the inheritor of their craft. The enormity of this epiphany occurs at Doody’s Cross in Camas; the enormity of the task that lies ahead also terrifies and haunts him.

One of that pathetic trio at Doody’s Cross in Camas was Aindrias MacCraith (c. 1710 – 1795). He was well known by his nickname, An Mangaire Súgach (The Merry Pedlar), which had been given to him by his mentor and great friend, Séan Ó Tuama an Ghrinn (c. 1708 – 1775). MacCraith was a roving Hedge School master, setting up school wherever he could find a few pupils, then moving on when numbers fell. From the accounts that have come down to us, we learn that the Mangaire was a quintessential Limerick Rake; fond of sport, good company and deep drinking, and getting into more than one scrape with the clergy on account of his various indiscretions.

Mannix Joyce, that great local historian and chronicler of The Poets of the Maigue, recalls that,

‘For all his waywardness, he was a gifted singer. That poor wretch of a man, so often seen reeling from the tavern to the miserable hovel he called home, was one of the sweetest poets an age of song was to produce, a man whose poems will endure as long as the Irish language lives. He was a real lyricist, not unlike Burns and in his songs, he gives us an insight into his wild and vagrant life. He had a profound knowledge of the Irish language, and his poetry is full of magic and melody. He belonged to that strange Hidden Ireland of the 18th century, that Ireland that flowered with such profusion of poetry under the blasting winter winds of oppression. If he was careless and intemperate, much of it was due to a hellish code of laws then being enacted for the utter degradation of the old race’ (Limerick Leader, 13th October 1945).

Rake that he was, he could often be found in the company of Séan Clárach Mac Domhnaill, convenor of the Maigue School of Poetry and composer of Mo Ghile Mear, originally from Charleville, who has been described as the ‘chief Jacobite Poet in Ireland’. Séan Ó Tuama, Fr. Nicholas O’Donnell, and those other poets of the Maigue were often to be found in his company, declaiming the hero-tales of Greece and Rome and discussing current European politics. Again, Joyce acknowledges the great contribution of those Maigue Poets during the harshest of Penal times:

‘Those remarkable men arose in an age when learning of every kind was banned in Ireland and sprang from a people dubbed as ignorant and illiterate by their oppressors. They were the last guardians of the thousand-year-old ure of the Gael, and with their passing the Irish language, the repository of that ancient ure, faded and died in the rich plains of Limerick’ (ibid).

One of Aindrias McCraith’s best-known songs begins with the line: ‘Slán is céad ón taobh so uaim’. The song is usually referred to by the title: ‘Slán le Máighe’ (‘Farewell to the Maigue’), or ‘Slán Chois Mháighe’ (‘Farewell to Coshma)’, the name of the local Barony. As mentioned already, Aindrias had a predilection for that dangerous combination of wine, women and song, and after one of many such indiscretions, he was exiled by the parish priest of Croom to Ballyneety, the place where Patrick Sarsfield destroyed the Williamite siege train in 1690. His sad, poignant lament from there is addressed to his great friend Seán Ó Tuama, who, along with MacCraith, was one of the leading lights of the Court of Poetry which assembled in the village of Croom (‘Cromadh an tSuaicheas’, ‘Croom of the Merriment’), with its headquarters in the inn which was run by Ó Tuama and his wife, Muireann. (The song is one of the great Irish slow airs and can be sung to the air of ‘The Bells of Shandon’).

Slán is céad ón daobh seo uaim

Cois Máighe na gaor na graobh na gcruach …

(A hundred and one farewells from this place from me / To Coshma of the berries, the trees, the ricks).

Then there was the pathetic refrain:

Och ochón, is breoite mise,

Can chuid gan chóir gan choip gan chiste.

Gan sult gan seod gan sport gan spionnadh,

O seoladh mé chun uaighnis.

(Alas, alas, sick am I / Without portion, without justice, without company, without money / Without enjoyment, without treasure, without sport, without vigour / Since I was sent away to loneliness).

John O’ Shea and Anna Jane Ryan play Slán le Máighe (Farewell to the Maigue) live at Nun’s Island theatre in Galway.

Only ten miles separate Croom from Ballyneety in County Limerick, yet an important boundary line lies between them. Croom, in County Limerick, is located in the barony of Cois Máighe (Coshma), whereas Ballyneety is located in the barony of Uí Chonaill Gabhra (Connello). So, the journey from one village to the other involved moving from one Barony to another; the equivalent in those days of moving from one jurisdiction to another. The title of the song (and its associated tune) is usually given in English as ‘Farewell to the Maigue’, as if the poet were saying goodbye to the river itself, which flowed majestically through his beloved place.

MacCraith’s ‘Farewell’, despite its sublime lyrics and haunting slow-air melody, is not meant to be taken at face value; it is meant as a ‘Slán go fóill’, as inconsequential a ‘Farewell’ as a French ‘Au Revoir’. He is, undoubtedly, showing off his great skill as a poet, but the reality is that he is being asked to take a temporary leave-of-absence from Croom until the current controversy abates. By its language and use of form, it is at once intentionally self-serious, theatrical and iconoclastic. Hartnett echoes this tone and mirrors this pose in his ‘Farewell’ – at times theatrical, self-serious, bombastic – but also, in a flash, heartfelt, exposed, human.

Unfortunately, Aindrias MacCraith did eventually have to bid a sad final farewell to his good friend and mentor, Séan Ó Tuama. It is doubtful if the Mangaire Súgach would ever have written a verse of poetry were it not for the encouragement and friendship of Séan Ó Tuama. He had written nothing before he came to Croom, and after the death of Ó Tuama, he lapsed into silence again. He left Croom and sang no more. He had outlived Séan Clárach (d. 1754) by almost 40 years and his friend, Séan Ó Tuama, by nearly 20. He had seen the last of the great Maigue School of Poetry, and his declining years were saddened by the decay of the old language in the district where once it flourished.

Of the three phantoms that accost Hartnett at Doody’s Cross in those early magical sections of ‘A Farewell to English’, Hartnett translated the work of Ó Rathaille and Ó Bruadair but not MacCraith, one of his great influences from the old dispensation, the Gaelic bardic past. However, we believe that MacCraith does play an important role in the naming of Hartnett’s poem, ‘A Farewell to English’. We know that Hartnett was obsessed with Croom, as the last bastion of the old Gaelic Schools of poetry. He took great pride in the fact that he was the only modern Irish poet to have been born in Croom – he spent his first few days in St. Stephen’s Maternity Hospital, located in the village! This near obsession with Croom and the Filí na Máighe (The Maigue Poets) may, therefore, have had some influence on Hartnett’s choice of title for ‘A Farewell to English’. Our theory is that Hartnett borrowed the title of Aindrias MacCraith’s most iconic and poignant poem, ‘Slán le Máighe’, for his own ‘farewell’ and self-imposed exile in West Limerick, where he had come to ‘court the language of my people’. MacCraith had been forced to move to nearby Ballyneety for a time because of his indiscretions, and in 1974, Hartnett decamped from the Dublin literary scene and set up home in rural West Limerick, ‘in exile out foreign in Glantine’.

Those ten years spent in Glendarragh were among the most productive of his career – it may not have been a permanent ‘Farewell’, but it was a productive one. It is obvious that this decision to ‘go into the Gaelic’ had been simmering for some time. Indeed, 1975 saw a flourish of publications, including A Farewell to English but also the iconic Cúlú Íde / The Retreat of Ita Cagney. Then, probably his most accomplished collection in Irish, Adharca Broic, was published in 1978, followed by An Phurgóid in 1983, Do Nuala: Foighne Crainn in 1984 and his fourth collection in Irish, An Lia Nocht, appeared in 1985. In parallel to this ‘serious’ output, he was writing and entertaining the locals with ballads, some serious or semi-serious like ‘A Ballad on the State of the Nation’, which was distributed as a one-page pamphlet like the ballads of old and even included original linocuttings by local artist Cliodhna Cussen. Other ballads were more contentious and even semi-libellous (or fully slanderous!), such as ‘The Balad (sic) of Salad Sunday’ and ‘The Duck Lovers Dance’. These latter creations were written under the very appropriate nom de plume, ‘The Wasp’! As time passed, Hartnett’s ‘farewell’, similar to MacCraith’s, was seen for what it was, a ‘Slán go fóill’.

During this period, he also undertook the translation of Daibhi Ó Brudair’s poems, which were published in 1985, and his obsession with these seventeenth-century precursors continued with his later translations of Aodhagán Ó Rathaille (1993) and Pádraigín Haicéad (1999). Finally, following his departure from Glendarragh, the collection A Necklace of Wrens (a collection of poems in Irish with translations in English by the poet himself) was published in 1987.

The inability of critics to pigeonhole Hartnett has been one of the major problems in sustaining his immense legacy. In turn, Hartnett’s continual search for a spiritual and cultural home has not made it easy. And his restlessness did not end. Once back in Dublin, there were more new beginnings, more farewells. Hartnett seemed to make yet another new beginning with Poems to Younger Women (1988). Then again, in Selected and New Poems (1994), those long poems such as ‘Sibelius in Silence’ or ‘The Man who Wrote Yeats, the Man who Wrote Mozart’, and ‘He’ll to the Moor’ mark still new accomplishments in his overall oeuvre. The truth, of course, is as Peter Sirr asserts, Michael Hartnett, ‘is the sum of all of these identity shifts, and to consider any one of these aspects in isolation is to miss the overall picture of a complex, restless and rewarding poet’ (Sirr, 294).

A half-century of hindsight allows us to have a clearer perspective. His very theatrical ‘Farewell’ from the stage of The Peacock Theatre needs to be understood, as he and Aindrias MacCraith meant it to be – merely a ‘Slán go Fóill’ – as inconsequential and as temporary as a French ‘Au Revoir’.

Postscript

In the late 60s and 70s, there was a very successful festival held annually in Croom, celebrating the work of the Maigue Poets. I came across this little gem while doing a bit of research in NLI back in February 2025. Hartnett was mightily peeved that he had not been invited as often as he felt he should. His papers contain a draft of a curse he put on the organising committee, written in Irish in the old Gaelic script. It transpired that he hadn’t been invited to the 1973 Féile, nor indeed to the 1972 or 1971 iterations either. He was not pleased, and so, in true bardic fashion, he placed a poetic curse on the organisers. Translated, it reads:

Whereas, I was born in Áth Cromadh an tSúbhacais thirty-two years ago, and as I am a poet who is famous the length and breadth of all of Ireland, even in British Ulster, and that I have received invitations to numerous poetry festivals in England and America and since I did not receive an invitation from my own people to the festival in the place of my birth this year or last year or the year before last, I hereby curse that festival – cuirim mo mhallacht orthu agus mallacht mo mhallachta,

Is mise,

Míchéal Ó hAirtnéada

(arna nglaoghtar Michael Hartnett sa Sacsbhearla, Priomhfíle Múmhan)

References:

Hartnett, Michael. A Farewell to English, Oldcastle County Meath, Gallery Press, 1975.

Hartnett, Michael. Cúlú Íde / The Retreat of Ita Cagney, Goldsmith Press, 1975

Hartnett, Michael. Adharca Broic, Oldcastle, County Meath. Gallery Press, 1978

Hartnett, Michael. An Phurgóid, Coiscéim, 1983.

Hartnett, Michael. Do Nuala, Foidhne Chuainn, Coiscéim, 1984.

Hartnett, Michael. An Lia Nocht, Coiscéim, 1985.

Hartnett, Michael. Ó Bruadair, Oldcastle: Gallery Press, 1985.

Hartnett, Michael. A Necklace of Wrens: Poems in Irish and English, Oldcastle County Meath, Gallery Press, 1987.

Hartnett, Michael. Poems to Younger Women, Oldcastle, County Meath, Gallery Press, 1988.

Hartnett, Michael. Haicéad, Oldcastle: Gallery Press, 1993.

Hartnett, Michael. Ó Rathaille: The Poems of Aodhaghán Ó Rathaille, Oldcastle: Gallery Press, 1999.

Hartnett, Michael. Selected and New Poems, Oldcastle, County Meath, Gallery Press, 1994.

Hartnett, Michael. Collected Poems, Oldcastle: The Gallery Press, 2001.

Michael Hartnett Papers, National Library of Ireland, 35,879/1, 35,879/2 (1)

Mannix Joyce / Mainchín Seoighe, folklorist and local historian from Tankardstown, Kilmallock, taken from his weekly column in The Limerick Leader called Odds and Ends, 13th October, 1945.

Sirr, Peter. Michael Hartnett, in Dawe G, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Irish Poets. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cambridge University Press; 2017, (Chapter 22: p. 294 – 306).

Walsh, Pat. A Rebel Act: Michael Hartnett’s Farewell to English, Mercier Press, Cork, 2012.

You must be logged in to post a comment.