I was never that good at Maths, and I’m so old that my Maths education consisted mainly of Geometry, Algebra and Trigonometry! Some of my teachers may even have been Greek; at least it was all Greek to me! However, if I were to represent where I stand politically, I’d probably use the more modern Venn Diagram. One bubble would represent the constituency covered by Christian Democrats, while the other bubble would represent the area covered by Social Democratic thought and policy. The oval intersection in the centre of this diagram is where I have stood politically since the ‘70s.

Firstly, two stories from the past. The first one I heard from my mother and her sister, my Aunty Meg. One evening in the Spring of 1932, shortly after Fianna Fáil had come to power, and a mere nine years since the end of the bitter Civil War, they were both on their way home from their National School in Glenroe. As they were passing a local farmer on the road, they shouted out, ‘Up Dev!’ which was the great political slogan of the day, following Eamonn De Valera’s victory in the General Election which had just taken place on March 9th that year. However, the following morning, both were brought before the class, and Aunty Meg was beaten about the head by her teacher, so that she was rendered profoundly deaf for the rest of her life. When their father, my Grandad, found this out, he went immediately to the school, withdrew his two youngest daughters and transferred them both to the convent school in Kilfinnane, five miles away, where they completed their education.

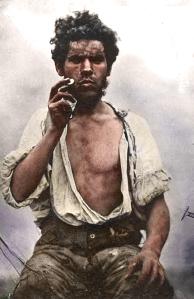

I also have a clear memory of the General Election in 1957. I remember my Grandad waiting patiently outside our home in Rapala, in the March sunshine, to be collected by local members of the Fianna Fáil political party who would take him to the Polling Booth in nearby Glenroe so that he could cast his vote in the General Election. I, even as a five-year-old, could sense how important this was to him. He was dressed in his best Sunday outfit, his flat cap, waistcoat and jacket, his trusty pipe, and his walking stick, ready for road! This was a regular occurrence in the ‘50s, and even in the ‘60s, when there were few cars, and the local activists of all political hues, who had cars, did everything in their power to maximise the vote! De Valera and Grandad’s beloved Fianna Fáil won the election, and so Grandad was very happy with that result.

So, my family would always have been traditionally staunch Fianna Fáil supporters, a support that had its origins in the horrible Civil War from whose ashes arose our fledgling Republic in 1923, the year my mother was born in Glenroe. However, since I became politically aware, I have always been drawn to the policies of Fine Gael, especially having read, while at University, Declan Costello’s Just Society document, which he had produced in the mid-60s.

Later, Garret FitzGerald’s Constitutional Crusade received my full support, and even though he never did seem to be cut out for the rough and tumble of Irish politics, I agreed with his liberal views and philosophy and the need to accelerate the separation of Church and State for once and for all. Following decades of deep conservatism at the top echelons of Irish life, FitzGerald in the ‘80s embarked on a bold odyssey to modernise and liberalise not only his own party but the country at large. However, his often-futile efforts, despite his Economics background, to fix the economic depression of the ‘80s met with less success, and, I suppose, thereby lies the enigma of a political visionary. In more modern times, visionary leaders of all political hues in Irish politics are in short supply.

One of my go-to commentators on Irish life since I began reading The Irish Times in the ‘70s, Fintan O’Toole, has recently stated that he believes Irish society is now firmly socially democratic. The big cultural shift was the breaking of the hegemony that had dominated the State – the tight alliance of Fianna Fáil and the Catholic Church. Demographically, Ireland is experiencing a very rapid catch-up after the long depredations of famine and mass emigration. Socially, the population has become both urbanised and highly educated. Added to this, the huge growth of the private sector economy has created an undeniable imperative for a greatly expanded State to provide infrastructure, housing, healthcare and education.

What we have, then, is a very broad consensus on the need for classic social democratic policies. Most people want to see an active State that builds houses, creates equal access to health and education, works to eliminate poverty and supports both those who need care and those (mostly women) who provide it. For this reason, I believe, Fine Gael, the political party that I have given my support to, is under serious threat today both at home and in Europe. This can be seen better in the European context, where they are aligned with the main Christian Democrat alliance in the European Parliament, the European People’s Party. Herein lies the threat: most Christian Democratic parties in Europe, to counter the threat from the far right, are themselves moving to the right in their pronouncements and their policies, especially on issues like immigration. These parties are being outflanked by the far right, and so, the middle ground is shifting to the right. Fine Gael is still considered a conservative party in Ireland, but in Europe, their associates are coming to view them as more Social Democrat than Christian Democrat – the centre cannot hold!

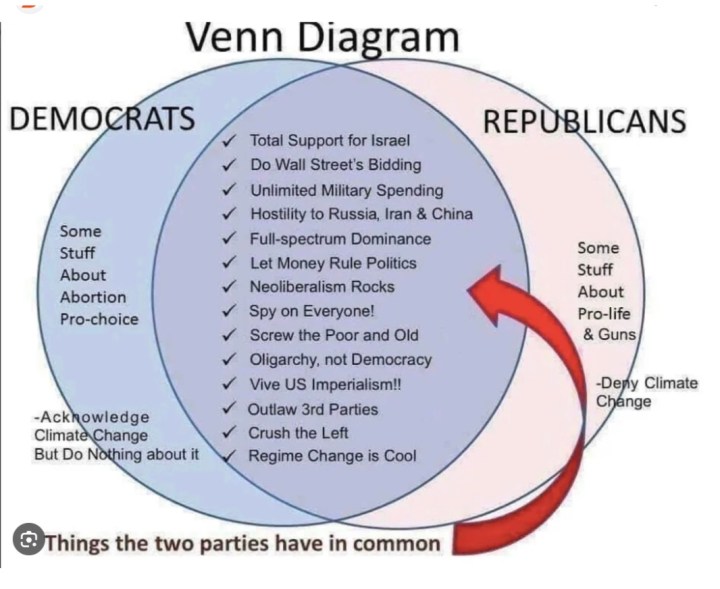

Politics has become very confusing in my lifetime. If I had a vote in American elections, my gut instinct would always have been to vote Democrat – yet today Democrats espouse many policies I find objectionable, such as being pro-abortion. Republicans, on the other hand, are pro-life, and so, God forbid, should I vote for Trump? If I were a British voter, I would find it easy not to vote for the Conservatives because of their extreme right-wing self-serving tendencies, but then I can’t warm to Keir Starmer and his version of the modern Labour Party either. Maybe we should do what we do in Ireland and ignore Left and Right, Conservative and Liberal, Republican and Democrat and simply have a Civil War and for the next 100 years vote for those on our particular side of that conflict!

Ironically, in this day and age, Democrats of every hue pay mealy-mouthed lip service to democracy. In Europe, we have built an immovable, stubborn and unwieldy bureaucracy in Brussels, and there is a perceptible democratic deficit. Decisions are made by consensus and take forever. Parallel to this, we have a pipeline of edicts and policies and over-regulation being handed down and implemented unquestioningly by local ‘sovereign’ parliaments in 30 member states. The stark reality is that despite its great wealth, Europe as an entity is weak and irrelevant, paralysed by conflicting national interests, when compared to the big players, Trump, Putin and Xi Jinping. Even when it comes to its own security, the EU struggles to be a central player.

Westminster, the Mother of Parliaments, gave us the concept that those who sat to the right of the Speaker were the Government and those who sat to the left of the Speaker were in Opposition. Yet today, the idea of robust parliamentary debate has almost vanished in our Houses of Parliament. Consensus politics is everywhere. For example, it was almost impossible to find an opposition voice in our Dáil to any of the recently proposed amendments to our Constitution. And in the recent Presidential Election, a pro-life candidate seeking a nomination failed to find the required 20 Seanad members to ratify her nomination, while our main political party, after much skulduggery, chose a non-party candidate to disastrous effect, thus undermining the office of President. Is it that all political parties agree because of the obvious virtue of the various proposals, or is it that the quality of those seeking nomination is so poor? Is their silence because of fear of being ridiculed and mocked because they are out of step? The question I ask is, who represents me? How come the people whom I voted for refuse to represent my position? Who speaks up for those who oppose these proposed measures?

My greatest dystopian fear is that there is a kind of elite consensus at work in our world and that, in effect, the lauded ideal of democracy is, in fact, long dead. This ‘elite consensus’ is agreed upon in such shady places as the World Economic Summit in Davos and other elite gatherings where the agenda is agreed upon and handed down to governments to implement. In recent years, it has been quite unnerving and unsettling to see our Taoisigh and Finance Ministers strutting in these undemocratic assemblies, cheek to jowl with billionaires, oligarchs and moguls of one hue or another. In my opinion, our political leaders have no place at such gatherings.

Lately, our government has increasingly hidden behind the very undemocratic Citizens’ Assemblies. These assemblies are meant to inform the government about proposed new legislation or other controversial issues. Nobody knows how these Assemblies are put together, or how their numbers are decided, yet our government continues to give them huge prominence in the determination of policy and legislation. If controversial decisions are arrived at, the government can wring their hands in phoney despair and claim that this, after all, must be what the people want and, thereby, distance themselves from any culpability.

Government-funded NGOs distort lobbying. In recent times in this country, we have had the ludicrous situation where the government have relied on, and paid, the National Women’s Council of Ireland to campaign for the removal of wording which refers to ‘women’, ‘mothers’, ‘marriage’, and ‘home’ from our Constitution – these terms are now considered old fashioned, gender-specific, and possibly offensive to some! These amendments were, in the main, poorly drafted and poorly thought through in terms of their future legal consequences and broader implications. Yet, this is how cosy consensus works: proposals are put to the people, who are generally disinterested and uninformed, and the government hopes that a low turnout will see the amendments carried. This surely is a travesty of democracy. I say this mainly because, in recent years, I find myself on the losing side in all these battles, similar to my unlimited heartbreak while following the Limerick hurlers until they began winning All-Irelands again in 2018!

The old concept of majority rule is now defunct. We are everywhere surrounded by vocal minorities, and the silent majority is being manipulated furtively, dangerously and relentlessly by social media and mainstream media, which has lost all vestiges of independence and objectivity. Newspapers and television stations have almost all been bought up by billionaire moguls and oligarchs for their nefarious ends. We are surrounded by a multiplicity of influencers whose sole objective is self-interest and self-promotion.

I remember back in 1984, the year our daughter Mary was born, thinking to myself that things weren’t that bad after all. Orwell’s chilling novel, 1984, had come and gone, and his dystopian predictions had been well off the mark. Of course, I was wrong. I remember again waking on November 8th 2016, to the news that Donald Trump was almost certainly going to be elected the 45th President of the United States of America. I had followed the seemingly interminable election campaign and had been amazed by his distortions, lies, deliberate misinformation and fake news, and now this buffoon, this bankrupt, had his finger on the levers of power in the most powerful country in our world. For me, the insanity, the instability began that day and has since spread like a pandemic to infect politics worldwide.

There is unfinished business here in Ireland, also. In the coming years, the country will have to face up to the challenge of reunification and try, in a peaceful way, to right the wrongs of the past. Seeking consensus won’t cut the mustard, and wise and strong leadership will be needed to bridge the gap to a new and better future for all on our beloved island. In truth, we have come a long way since the days of ‘Ourselves Alone’. We are now an outward-looking nation, and, despite its many perceived shortcomings, Europe has been good for us. Yet, the very notion of a Border Poll has been kicked down the road by even the most rabid Republican parties for fear it will offend some group or other. If a week is a long time in politics, then one hundred years is an eternity.

It is very hard to have to say that our present government, and its political administration, are in deep paralysis and stasis since it came to power over a year ago. For years, on the global stage, we have resembled a recalcitrant college student who wants to experience the college atmosphere but prefers to spend his time in The Stables and The Scholars Club, even The Terrace, without ever going to a lecture or meeting the least onerous deadline. We haven’t met a deadline, set by ourselves or Europe, in years, and we are paralysed by regulations which we have agreed to when we try to respond to any crisis, notably housing for our young people or the climate emergency. Added to this, the cosy consensus of ‘a rotating Taoiseach’ is not working, and my favoured political party has not chosen its leaders well in recent years. Too many talented politicians are simply biding their time until lucrative opportunities arise at some global think tank, bank or other.

For most of my lifetime, I have admired from afar the United States of America and the United Kingdom. I have long been assured and comforted by their perceived role as leaders and policemen of the free world and their reliance on ‘a rules-based world order’ of multilateral organisations, such as the UN and the International Criminal Court. It saddens me to have to admit that their stature in my eyes has been diminished and shattered by their actions and inactions in this 21st century. Being complicit in genocide is the least of their crimes.

The bottom line is that a whole range of sacrosanct core principles are being tampered with – even decimated: our democracy, our sovereignty, and our neutrality. America has gone rogue, and the checks and balances have been cast aside. Where is Congress? Where are the lawmakers and law upholders of the great American Senate? And what of the Stock Markets, that supposedly great regulator and our ultimate wind vane of economic insanity? Why are they not freaking out at developing events? What has their reaction been to all this upheaval and instability? There is a feeding frenzy ongoing, and all are gorging themselves at Trump’s Trough.

How easily all these safeguards have been cast aside by those who are putting personal aggrandisement before the common good. Government-backed armed militias roam the streets of American cities, shooting dead American housewives collecting their kids from kindergarten. To quote W.B Yeats, in The Second Coming, a prescient poem for our time also,

…. Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned ….

Social anarchy and massive destruction are made worse by the collapse of moral values among the leaders of nations: ‘The best lack all conviction, while the worst / Are full of passionate intensity’. Back in 1919, Yeats predicted that evil would triumph in the public sphere because those political leaders who might be expected to defend humane values (and basic human rights) lack the determination to resist those who preach violence and intolerance.

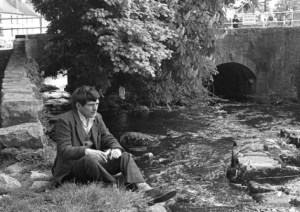

It is undisputed that all wars and all politics are, in fact, local. Sometimes our political leaders forget this universal truth to their cost. Like Patrick Kavanagh in his beautiful sonnet, Epic, ‘Gods make their own importance’ and the boundary dispute between the Duffys and the McCabes and their ‘pitchfork-armed claims’ is as important as any other conflict making headlines in the morning papers. My advice to those who purport to represent me is to get out of their ivory towers and retrieve the better parts of what we used to call in Ireland ‘parish pump politics’, namely listening to the people who voted them into their positions of power in the first place and to forcibly represent those views on the floor of the Dáil.

Finally, despite my pessimism and present disillusionment with politics and politicians, it is a source of great pride to me that, down the years, at least three of the brave politicians, and one brave Minister, who have regularly called to my door seeking my vote have, at one time, sat before me in class!

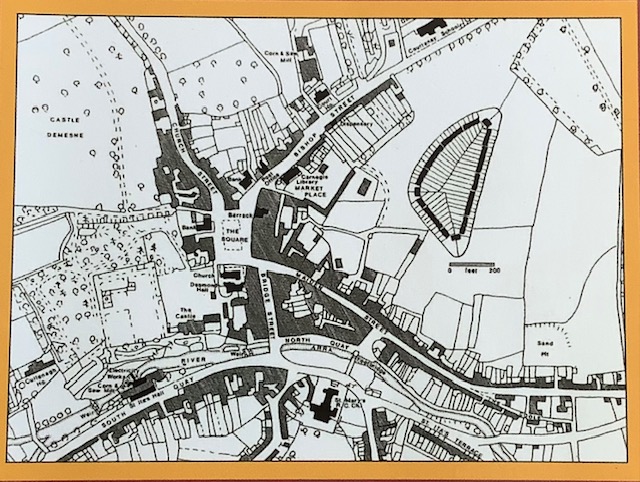

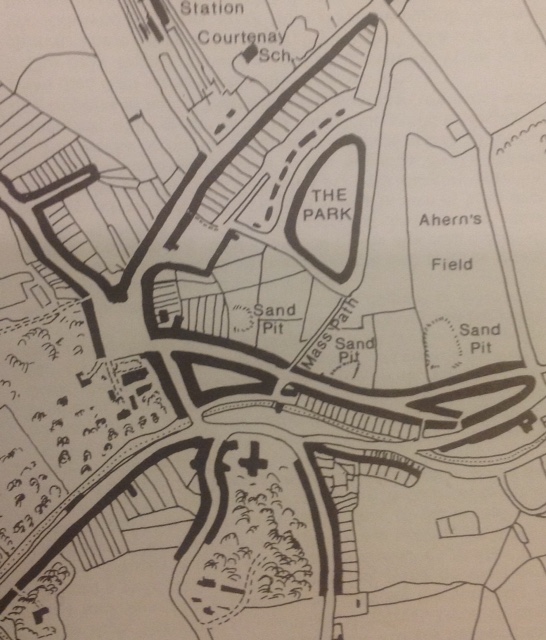

Translations is a three-act play by Irish playwright Brian Friel, written in 1980. It is set in Baile Beag (Ballybeg), in County Donegal which is probably loosely based on his beloved village of Glenties in West Donegal where Friel was a frequent visitor and where he is buried. It is the fictional village, created by Friel as a setting for several of his plays, including Dancing at Lughnasa, although there are many real places called Ballybeg throughout Ireland. Towns like Stradbally and Littleton were other variations and ‘translations’ of the very common original ‘Baile Beag’. In effect, in Friel’s plays, Ballybeg is Everytown.

Translations is a three-act play by Irish playwright Brian Friel, written in 1980. It is set in Baile Beag (Ballybeg), in County Donegal which is probably loosely based on his beloved village of Glenties in West Donegal where Friel was a frequent visitor and where he is buried. It is the fictional village, created by Friel as a setting for several of his plays, including Dancing at Lughnasa, although there are many real places called Ballybeg throughout Ireland. Towns like Stradbally and Littleton were other variations and ‘translations’ of the very common original ‘Baile Beag’. In effect, in Friel’s plays, Ballybeg is Everytown.

You must be logged in to post a comment.