Some like Anfield, some prefer Wembley or the Camp Nou or Santiago Bernabéu; some prefer Thomond Park or Cardiff Arms, but my favourite ‘field of dreams’ is Semple Stadium in Thurles, County Tipperary, where the GAA was founded over 140 years ago. It has been at the heart of hurling since its opening in 1910. Tipperary people, harking back to long-gone glory days in the 60s, refer to it as the Field of Legends, but I’d say Limerick people would have something to say about that after our recent run of success since 2018!

Close your eyes …. Think of summer. What do you see? I see midges swooping and dancing through a languid sunset. I see heat-drenched Limerick jerseys shuffling through the streets of Thurles, where bellows of banter waft along with the whiff of cider that floats from the open doors of packed pubs in Liberty Square. Inside D D Corbett’s, a bitter alcoholic draws tears from the crowd with a soft, sweet rendition of ‘Slievenamon’.

Anyway, I have been travelling to this Mecca since I was ten years of age. My first visit was on a beautiful Sunday, the 8th of July in 1962. My mother and father, along with most of my brothers and sisters at the time, were walking home from second Mass in Glenroe when Tom and Mick Howard stopped in their black Morris Minor and asked Dad and me if we’d like to go to Thurles with them to see Ringy and the Rebels take on the might of Tom Cheasty, Ned Power and Frankie Walsh’s Waterford. It was Ring’s last hurrah, and it was appropriate that his last Championship game in the ‘blood and bandages’ of his native Cork should have been in Thurles. It was here that, for two decades previously, he had adorned the ancient game with his unique and exceptional talent. I count myself lucky that I was able to sit there with my Dad, a loyal Cork man, and my hurling mad neighbours, the Howard brothers, on the recently creosoted railway sleepers on the embankment that is now the Old Stand. However, it was Waterford’s day, and they won by 4 – 10 to 1 – 16.

On a street corner, a humming chip van mumbles its invitation to giddy children as the June sun beats down. The Pecker Dunne sits, perched on a flat stone wall, plucking and strumming, twanging banjo chords as he winks at those who pass. A smile broadens his foggy beard as coins glint and twinkle from the bottom of his banjo case.

I have witnessed other great games there down the years, and I have seen great hurlers adorn the venue. Let’s be blunt – Thurles is the best place to go to see a hurling match, and hurling people also know that if you can’t hurl in Thurles, you won’t hurl anywhere. I remember listening to Michéal O’Hehir commentate on the 1960 Munster Final in Thurles between an ageing Cork team and Tipperary, who were emerging as a force to be reckoned with. There’s a story told by John Harrington about the speech Christy Ring gave in the dressing room before the game that day. He delivered a rousing speech that brought the blood of his teammates to boiling point. However, his words did not find favour with Fr Carthach McCarthy, who was also in the dressing room at the time. “You didn’t find those words in the Bible, Christy”, said Fr. McCarthy, in as disapproving a tone as he could muster. Ring cast a jaundiced eye at the man of the cloth and replied, “No, Father. But the men who wrote the Bible never had to play Tipperary.” Despite his exhortations, Cork lost on the day, 4 -13 to 4 -11.

Hoarse tinkers flog melted chocolate and paper hats on the brow of a humpbacked bridge as we move closer to the field of legends. The drone of kettledrums and bagpipes rises from the Sean Treacy Pipe Band as they parade sweat-soaked warriors around the green, hallowed sod.

John D Hickey, one of the great sports writers of the 50s and 60s, coined the phrase ‘Hell’s Kitchen’ to describe the general vicinity of the Tipperary goalmouth, which Michéal O Hehir, the greatest GAA commentator of all time, referred to as ‘the parallelogram’, or what we today refer to as ‘the square’! This area of the pitch was patrolled in the mid-60s by the Tipperary full-back line at the time, Michael Maher at full-back, flanked by John Doyle and Kieran Carey – probably the greatest full-back line in the history of the game. As the name suggests, they usually generated the sort of heat that suffocated most full-forward lines, who generally struggled to cope with their unique blend of physicality, hurling skill and a generous helping of the dark arts. Their dominance continued until the emergence of the youthful Eamonn ‘Blondy’ Cregan and Eamonn Grimes and company, who in 1966 destroyed that Tipp team that were All-Ireland winners in ’61, ’62, ’64, and ‘65. Suffice it to say that Limerick put a stop to Tipperary’s gallop that sunny Sunday, and the young ‘Blondy’ Cregan scored 3 goals and 5 points in a 4 – 12 to 2 – 9 defeat of Tipperary. That day still stands as one of my all-time treasured sporting memories.

A whistle rings on high, ash smacks on ash and the sliothar arrows between the uprights. A crash of thunder and colour erupts from the terraces at the Killinan End and the Town End (the Limerick end!)…… I see the Munster Championship!!

I’ve been in Thurles as a Limerick supporter, as an uninvolved spectator, and I’ve also been there with skin in the game as Don played Minor, Under 21, and Intermediate hurling for Limerick. Limerick have been lucky in this place. A few Munster Senior titles, including 1973, five Under 21 titles in this Millennium alone, and a Centenary Minor title after a replay at the same venue against Kilkenny. Paddy Downey, writing in The Irish Times, said of the replayed minor final that, ‘it is probably true to say that there never has been a better minor All-Ireland final’.

The 1973 Munster Final was special, and of course, it ended in controversy. As the final seconds ticked down and the teams were level, Eamonn Grimes won a disputed seventy for Limerick. The referee, Mick Slattery from Clare, told Richie Bennis that he had to score direct, as the time was up. Richie held his nerve, the sliothar headed goalwards, the umpire raised the white flag, and the rest is history. Every Tipperary man there that day swears that the ball was wide, but it mattered little; the game was up. In my view, it was Ned Rea who broke Tipperary hearts that day with his three goals and not Ritchie Bennis with his last gasp point. Sadly, it was the final swansong for that great Tipperary team. They stole an All-Ireland in ’71 when they beat Limerick in the rain in Killarney, but they didn’t emerge again as a hurling force until 1989. That day also marked the legendary Jimmy Doyle’s last appearance in a Tipperary jersey.

The Championship is more precious than life for many. I’ve seen grey-haired men gazing into half-empty pints, reeling off the names of the great ones, like prayers. I’m afraid I too follow suit. Ask me who the Minister for Finance is, and your question will be greeted with indifference. I simply couldn’t care less. But ask me where Carlow senior hurlers play and instantly I say, ‘Dr. Cullen Park … to the left at Church Street, up Clarke Street and half a mile out on Tower Road’. Monaghan? ‘Pairc Ui Tieghernan .. on the slope of George’s Hill, overlooking the County town’. Where do Sligo play? ‘Markievicz Park in the heart of Sligo town’. ‘Bless me, father, for I’m a fanatic!’

The major hurling powers took a bit of a break in the mid-90s and allowed the minnows, like Limerick, Clare and Offaly and Wexford, to have their fling. Don and I were in the New Stand – Árdán Ó Riain – for the ’95 Munster Final on the 9th of July. It was one of those glorious Thurles days – despite the outcome. In the end, Clare claimed their first Munster championship since 1932, and only their fourth ever. I remember Davy Fitz scoring a penalty before half-time, crashing the sliothar high into the town net, before sprinting back to his own goal line. Despite our disappointment, especially after the humiliating defeat in the All-Ireland Final the previous year to Wexford, you had to give credit to this Clare team. One could sense the ghosts of 63 years and the curse of Biddy Early evaporating before our eyes. The release of emotion when Anthony Daly received the cup had to be seen to be believed. I remember the ‘Shout’ ringing out from the Killinan End and then Tony Considine taking the microphone for his rendition of ‘My Lovely Rose of Clare’.

What else draws the likes of Mike Quilty and Mike Wall, setting them down among roaring, red-faced lunatics in the shadow of the crowded Old Stand? What else exists that plucks the cranky farmer from the milking parlour and flings him into a concrete cauldron eighty miles across the province? Some swear the Apocalypse would not have the same effect….

We waited nearly a full year to gain our revenge – on June 16th, in Limerick this time. We had been away for a holiday in Carnac in Brittany and came back the day before the game. All of Limerick had been convulsed by the recent killing of Detective Garda Jerry McCabe, who had been shot and killed in the village of Adare by members of the Provisional IRA on June 7th, during an attempted robbery of a post office van. His colleague, Ben O’Sullivan, had also been seriously injured in the incident. Being away when tragedy strikes so close is unnerving and surreal. I spent most of that Saturday hunting for tickets for the fanatics in my household and eventually secured terrace tickets at the City End of Pairc na nGael from Charley Hanley in Croagh, who was Liaison Officer with the Limerick team at the time. The following day, in glorious sunshine, we took our sunburnt revenge. Hurling legend Ciarán Carey of Patrickswell scored one of the greatest ever winning points in the history of Gaelic Games, in front of an attendance of 43,534. Result: Limerick 1-13, Clare 0-15.

May and the chirp of the sparrow, you can be guaranteed we’d be stuck in that long snake of traffic, as it slithered its way to Cork, Limerick, Thurles and other far-flung fields.

The modern Munster championship has changed many an inherited dynamic. The regularity with which Limerick now go to Semple Stadium to play Tipperary is a very modern phenomenon. There was a time when if you played two Munster rivals, you would be through to an All-Ireland semi-final – not anymore. Now you must beat all the Munster counties at least once in the Munster Round Robin Pool of Death. Limerick have won five All-Irelands in this way since 2018. Two Munster counties in an All-Ireland Final is no longer a rarity.

.… But oh to be a hurler… If the truth be known, I couldn’t hurl spuds to ducks. The boss of my hurley has seen the arse of a Friesian cow more often than it has the crisp leather stitching of an O’Neill’s sliothar! Okay, I’ve had my own All-Irelands up against the gable end and in and around the mother’s flower beds, but that’s as far as it went for me.

What is most amazing about Thurles is that no matter who is playing, they all seem to troop back into the town and mingle in the Square in the shade of Hayes’s Hotel for hours afterwards. As Kevin Cashman, that Prince of Sportswriters from my generation, remarked, ‘the pubs of Thurles on a big match day have something that no other pubs can give. It has been called ‘atmosphere’, ‘bond’, ‘fraternity’, and much more – it’s magic in the air’. The ghosts of Mackey, Clohessy, the Doyles, John Keane, Jimmy Smyth, and Ring become as real as what you have just witnessed. And now we have new heroes like Nickie Quaid, Declan Hannon, Cian Lynch, Barry Nash, Kyle Hayes, Patrick Horgan, Tony Kelly, Shane O’Donnell, the Mahers, and Austin Gleeson to keep the flame alight for future generations. As Kevin Cashman puts it, ‘This is their Elysian field and the turf, and the grass and even the steel and the concrete of this place are the keepers of their youth and the youth of all of us, who shaped them’.

The terrace is where the real nectar of hurling comes to a head – when every Joe Soap in the country stands together on the same patch of cement with their eyes fixed on the same lush, green carpet…..

References

Harrington, John, Doyle: The Greatest Hurling Story Ever Told (2011).

Highly Recommended

O’Donnchú, Liam. Semple Stadium: Field of Legends, Dublin: O’Brien Press, 2021

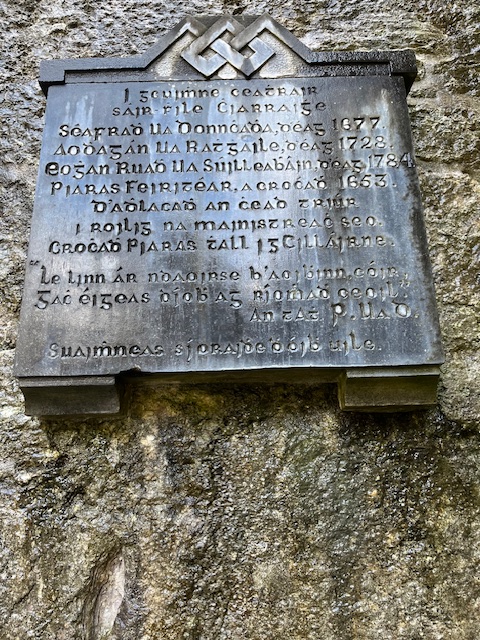

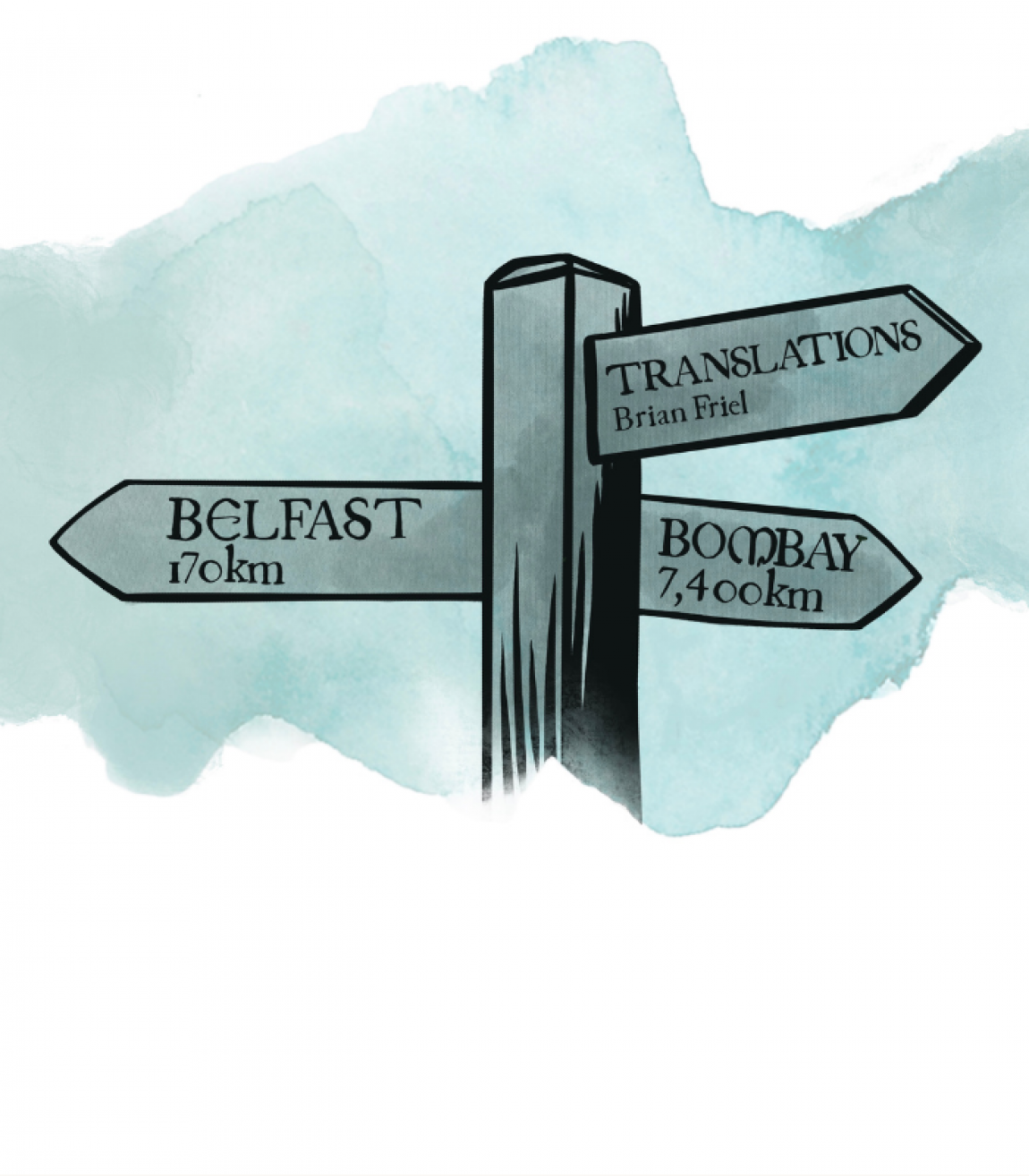

Translations is a three-act play by Irish playwright Brian Friel, written in 1980. It is set in Baile Beag (Ballybeg), in County Donegal which is probably loosely based on his beloved village of Glenties in West Donegal where Friel was a frequent visitor and where he is buried. It is the fictional village, created by Friel as a setting for several of his plays, including Dancing at Lughnasa, although there are many real places called Ballybeg throughout Ireland. Towns like Stradbally and Littleton were other variations and ‘translations’ of the very common original ‘Baile Beag’. In effect, in Friel’s plays, Ballybeg is Everytown.

Translations is a three-act play by Irish playwright Brian Friel, written in 1980. It is set in Baile Beag (Ballybeg), in County Donegal which is probably loosely based on his beloved village of Glenties in West Donegal where Friel was a frequent visitor and where he is buried. It is the fictional village, created by Friel as a setting for several of his plays, including Dancing at Lughnasa, although there are many real places called Ballybeg throughout Ireland. Towns like Stradbally and Littleton were other variations and ‘translations’ of the very common original ‘Baile Beag’. In effect, in Friel’s plays, Ballybeg is Everytown.

You must be logged in to post a comment.