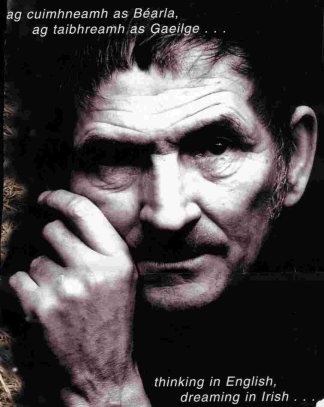

A Singular Life: The Poet Michael Hartnett

Theo Dorgan

All poets are singular, in the sense that we are all singular, each of us bearing the burden of one life and one life only, but also in the sense that no poet can be comfortably placed in a definite lineage, presented to us as a manifestation in one particular line of tradition. Michael Hartnett was more singular than most. He was of Munster, and he acknowledged Munster forebears, but if this was the place he started from, he was unpredictable and cosmopolitan in his tastes and in the company he would keep; nothing in his background could have predicted or predetermined the poetry he would make, the arc his life would take.

- Birth and a people

He was born in 1941, in Croom, County Limerick; he grew up in Newcastle West, in a time of close horizons, small expectations and apparently narrow minds. In those days, for the children of the poor, the prospects were few; the best hope was emigration, offering what the country could not – work and a living, however diminished. For the waywardly gifted, however, there is always the opportunity to carve out one’s own niche, albeit at the sacrifice of comfort and social place as generally understood. The State was barely thirty years old and had already abandoned the revolutionary promise to cherish its children equally when Michael Hartnett stepped outside the boundaries of class and predestiny to discover himself a poet.

He published his first work in a local paper at the age of thirteen, his first poem in The Irish Times when he was still a schoolboy. From the day he left school, he thought of himself first and always as a poet.

- A poet of and from a particular place

In an interview with Dennis O’Driscoll, Hartnett says: ‘I’m the only ‘recognised’ living Irish poet who was born in Croom, County Limerick, which was the seat of one of the last courts of poetry in Munster: Seán Ó Tuama and Aindrias Mac Craith. When I was quite young, I became very conscious of these poets, and, so, read them very closely indeed.’[1]

In small places, folk memory runs deep, and a certain cachet endured in the title ‘poet’, with connotations of ‘other’, ‘different’, ‘gifted’, and ‘dangerous’. With the niche already prepared, so to speak, one sees the attraction for a curious young mind, already verbally adept and quick: poetry offered place, ancestry, a degree of acceptance for the chosen path and open horizons for a young man who had already discovered the power of words.

It is hardly uncommon, in a young poet, that she or he would first begin to grow in the shelter of some chosen poet mentor, whose sensibility, or technique, or more usually some amalgam of both, opened a road forward in the craft. When Hartnett first sought such a precursor, he looked at his immediate local context and backwards into another time and another language. What he found there would make no discernible impact on his craft (he never translated the totem figures, Mac Craith or Ó Tuama) but they furnished him with a particular kind of warrant – he could and did think of himself as the favoured inheritor of a tradition, and also as one obliged to be loyal to that tradition. This sense of obligation would become the sign and signature of his work.

Few Irish poets writing in English would own fealty to the tradition of Irish language poetry in the way that Hartnett did; his contemporaries and near-contemporaries chose figures who were perhaps as close to home but were certainly nearer in time, in language and in their themes and subjects. His Irish at the time was meagre, mostly acquired through overhearing Bridget Halpin, his grandmother, speak at late night firesides when the child had been safely put to bed. Much of his childhood was spent in her Camas cottage. He would later claim that she was one of the last native speakers of Irish in the district. While there are grounds for doubting this, his grandmother had a formative influence on the poet’s imagination – he would say that once she saw him with a necklace of wrens circling around his head, leading her to proclaim him a poet. He relished this atavistic sense of recognition, and would celebrate his grandmother in one of his most famous poems, ‘Death of an Irishwoman’[2]:

Ignorant, in the sense

she ate monotonous food

and thought the world was flat,

and pagan, in the sense

she knew the things that moved

at night were neither dogs nor cats

but púcas and darkfaced men,

she nevertheless had fierce pride.

But sentenced in the end

to eat thin diminishing porridge

in a stone-cold kitchen

she clenched her brittle hands

around a world

she could not understand.

I loved her from the day she died […][3].

It is a far more cold-eyed tribute than the earlier, more conventional ‘For my Grandmother, Bridget Halpin’, a sign that Hartnett is willing to acknowledge ancestry but also to strike out in his own particular direction.

- Elected Company

Poets will gather about themselves, by elective affinity, those ancestors and companions that they need, not those wished upon them. We are more likely to understand them when we allow them to fly free in their chosen company.

Hartnett’s chosen companions were both eclectic and wayward, the company he chose as he pursued his life in poetry but also formed a consistory to whom he felt himself bound in loyalty and comradeship. Thus, in ‘A Farewell to English’ (and the indefinite article here is significant), these lines:

I say farewell to English verse,

to those I found in English nets:

my Lorca holding out his arms

to love the beauty of his bullets,

Pasternak who outlived Stalin

and died because of lesser beasts;

to all the poets I have loved

from Wyatt and Robert Browning;

to Father Hopkins in his crowded grave…[4]

The plangent concluding lines of Antoine Ó Raifteirí’s poem ‘Cill Aodáin’ are these: ‘S dá mbeinn-se i mo sheasamh i gceartlár mo dhaoine/ D’imeodh an aois díom is bheinn arís óg.” A working translation: “And were I standing right at the heart of my people/ Age would go from me and I would be young again.”

I invoke these lines because to understand Michael Hartnett, it is of the first importance to recognise that ‘mo dhaoine’, ‘my people’, gives us both provenance of the man, and hence of the work, and also the mandate that governed and guided his trajectory on this earth, from first to last.

Hartnett, throughout his life, referred back to his sense of a people, defined and redefined that community to encompass family, neighbours and friends, antecedent poets, and that tribe of audience and influence, an intelligible company chosen by elective affinity. He wrote always for his place and for his people, sometimes as if in a guided trance, but always aware of the bond as both necessary and inescapable. If he was sometimes at home in and sometimes estranged from both place and people, if this community was sometimes balm and sometimes bane, nevertheless, this was the territory in which he lived out his life and to which he felt honour bound.

The territory encompassed by his native Newcastle West and neighbouring Camas and Templeglantine, extending outwards to the province of Munster and on to Dublin, touching on Spain and the Classical world in its farthest rippling, while vertically, so to speak, reaching back for Ó Tuama, Ó Bruadair, Ó Rathaille, Sor Juana Iñes de la Cruz and Federico García Lorca.

He would show a lifelong fidelity to his birthplace, but he had no illusions about the soul-cramping truth of a small place where ambition was suffocated in the cradle. The early poem, ‘A Small Farm’, begins:

All the perversions of the soul

I learnt on a small farm,

how to do the neighbours harm

by magic; how to hate.

I was abandoned to their tragedies,

minor but unhealing:

and concludes, the repeated line adding emphasis,

I was abandoned to their tragedies

and began to count the birds

to deduce secrets in the kitchen cold,

and to avoid among my nameless weeds

the civil war of that household.[5]

- The Early Work

The early poems are mannered, veering close to the Symbolism of the Russian Silver Age, marking a territory of savagery, death, and disappointment in a stylised language that only rarely swerves into the high plain speech that would become his signature music.

We hear this true note first and best in Anatomy of a Cliché (1968).[6] There are birds here, but there is also ‘cold rain glisten/hung on each shocked feather’, the feel of the actual intensely experienced, even if birds are sometimes co-opted as metaphor, as in poem XI,

my lovely woman, listen:

two birds came together

out of a cold rain,

one, small, but capable of song,

one with strange plumage

not of the local lands [7]

Hartnett had been five years in Dublin when this collection appeared, but as Michael Smith points out: ‘Michael arrived in Dublin as an already published poet who was not looking for, nor needing any, teachers in the art of poetry.’ [8]

Smith tells us that Hartnett enrolled as a student in UCD, thanks to patronage from James Liddy, but ‘Michael almost never attended a lecture’. He found the University congenial, not so much for its teaching, but because it placed him in a company of young poets, including Macdara Woods, Smith, Eamon Grennan, Brian Lynch and, importantly, Paul Durcan. Hartnett and Durcan shared a common belief in poetry as a high calling that demanded surrender, devotion, and a single-mindedness, elevating it above all other duties. It is no reflection on their contemporaries to say that Hartnett and Durcan considered it something of a sacred moral imperative to stand at a slant to the shared social world, to embrace a certain kind of high loneliness. In Hartnett’s case, this high loneliness would be tuned to a keener pitch when, in 1975, he made the momentous decision to switch from writing in English to writing in Irish.

- Farewell to English

A Farewell to English,[9] published in that year, was a watershed book for Hartnett. Much of the attention this collection continues to draw is focused on the title poem, at the expense of the complex array of signalling in the poems that lead up to it. There is the acknowledgement of the toxic, particular nexus of alcohol and poverty in ‘The Buffeting’ and in ‘Early One Morning’, self-excoriating poems that are both clinical and merciless in their impact. There is the archetype of the fated and fatal victim in ‘The Oat Woman’, a figure to equal anything Graves, or Pasternak, can conjure, and there is its twin poem, ‘Death By The Santry River’ – both poems are stalked by terror. There is that ferocious political poem ‘USA’, and there are the poems that circle back to the home place – ‘Mrs. Halpin and the Lightning’, ‘Pig Killing’, ‘A Visit to Croom 1745’. Hartnett may be seen to be preparing his case for the title sequence, reaching back to his first circle of belonging, then nodding towards his second circle of elective affinities (in ‘Struts’, for example, with its ‘We are climbing upwards into time/and climbing backwards into tradition’), before he plunges forward into the Grand Declaration. Before we get there, we should take a long, cool look at ‘A Visit to Castletown House’.

The great Palladian mansion, Ireland’s first and still its finest, was built to consolidate and further the social and political designs of William Conolly, speaker of the Irish House of Commons. Begun in 1722, completed in 1727, it was both a residence and a symbol of Irish achievement and ambition. The political congresses envisioned by Conolly never took place there, but the house did come to represent a phase in the evolution of a new kind of politics in Ireland, and much of the thinking about quasi-independence from direct British rule was fostered there. Of course, Castletown House was also a centre of dominance as far as the poorer classes were concerned, a ‘Big House’ carrying all the complex baggage that term implies.

Set in lush countryside on the banks of the wide, slow-moving Liffey, Castletown stood as a monument to what might be called the aristocratic pastoral. Hartnett’s poem moves through that pastoral landscape to an acknowledgement of the building in the “mere secreting wood”, overthrown at the cost of knuckles that bled and bones that broke, to a sharper focus on the pretensions of the nouveaux riches and on to the precise bitterness of the closing five lines:

I stepped into the gentler evening air

and saw black figures dancing on the lawn,

Eviction, Droit de Seigneur, Broken Bones:

and heard the crack of ligaments being torn

and smelled the clinging blood upon the stones. [10]

The poem may be read as a prologue to the title sequence of the collection. The relentless drive to its pitiless conclusion, the brief rehearsals of what were already central themes in the poet’s work, are interrupted by stanza four, introducing a new theme that will manifest with increasing power in later poems such as ‘Sibelius in Silence’: Hartnett’s deep insight into music as a high art.

It would be simplistic to read Hartnett’s turning away into Irish as atavism, as an arbitrary and wilful gesture. He was already an assured presence as a poet in English, a distinctive, recognised and recognisable voice. If he had an inherited sense of the rightful grievances of the poor, the landless and powerless, and the political acumen to understand the power relations that had evolved through Ireland’s colonised history, he had also a cool and sophisticated grasp of high art, as evidenced in this fourth stanza:

…the music that was played in there –

that had grace, a nervous grace laid bare,

Tortellier unravelling sonatas

pummelling the instrument that has

the deep luxurious sensual sound,

allowing it no richness, making stars

where moons would be, choosing to expound

music as passionate as guitars.[11]

Here, on the point of turning away from a language he had already mastered, Hartnett is sounding what will surface as a powerful strain in his later work: his deep understanding of and affinity with a broad European aesthetic. Sections (iii) and (iv) of ‘A Farewell to English’ are satires, in the Gaelic tradition of the ‘aor’, a form of invective that holds up its target to a savage form of ridicule. Dennis O’ Driscoll misses the point when he dismisses these sections as “philistine nonsense”; I think he misses the humour of these sections, the delicate and deliberate brio of exaggeration which Hartnett artfully deploys his point, as he says himself in the interview with O’ Driscoll, is that he was infuriated by the neglect of, and the lip service paid to, the Gaelic language and the Gaelic poetic tradition. In taking a deliberately hyperbolic swipe at the guardians of what had become State culture, he is making a subtler point: you cannot make all-encompassing claims for Irish identity and Irish poetry when what you mean is Irish poetry in English, an Irish identity that manifests only in English. The argument is made most pointedly in section vi), where the second stanza is brutally dismissive of “our Governments”, and follows hard on the heels of the last two lines in the first stanza: “For Gaelic is our final sign that/ we are human, therefore not a herd”. [12]

Sections iii), iv) and vi) are best thought of as a flourish of the matador’s cape, a heightening of the dramatic temperature to mask sober and serious business. Hartnett experienced poetry as a calling; he felt himself bound by an imperative from elsewhere that was a cloudy blend of local tradition in folklore and literature, a sense of his duty to speak for his class, his wide and miscellaneous reading and the imperatives he drew from that reading. He himself offered various reasons for turning away from English, which may be summarised as a reluctance to see the language go down into the dark. But consider, he had little Irish himself, there were already contemporaries such as Caitlín Maude, Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill, Michael Davitt and others who were effectively driving a mini-renaissance in Irish language poetry – the survival of the language did not depend on Hartnett’s frail and hesitant voice, and he was intelligent enough to know this:

This road is not new.

I am not a maker of new things…

…But I will not see

great men go down

who walked in rags

from town to town

finding English a necessary sin

the perfect language to sell pigs in.

I have made my choice

and leave with little weeping:

I have come with meagre voice

to court the language of my people.[13]

We should not forget that the long decay of the Irish language as a vernacular, and as a literary language, was neither an organic nor an unavoidable phenomenon. The former colonial power had an explicit and effective policy for the extirpation of the language, and this, coupled with the brute post-Famine necessity to privilege English to find a foothold in the English-speaking lands towards which forced emigration was inevitably directed, drove what we might call an evolutionary adaptation.

Hartnett, meagre though his store of Irish was, felt impelled to stand for the lost civilisation, the neglected and imperilled element that he thought crucial to Irish identity. How much of his argument was deeply felt, how much was post-hoc rationalisation, will be argued for a long time but need not detain us, since there was a deeper imperative at work. To put it as simply as possible, it is not so much that Hartnett chose Irish as that Irish chose him. The words came “like grey slabs of slate breaking from/an ancient quarry, mánla, séimh, dubhfholtach, álainn, caoin”.[14]

Out of nowhere, the words came to him, and he felt himself summoned:

I sunk my hands into tradition

sifting the centuries for words. This quiet

excitement was not new: emotion challenged me

to make it sayable.[15]

It was the words themselves, as they drifted into his consciousness, that prompted this radical departure from ‘the gravel of Anglo-Saxon’. He does not suggest that he followed unquestioningly:

What was I doing with these foreign words?

I, the polisher of the complex clause,

wizard of grasses and warlock of birds

midnight-oiled in the metric laws?

Section ii) offers two further imperatives: he sets out to walk to Camas, “half-afraid to break a promise” made to his uncle Dinny Halpin, and on the way he encounters ghosts, “black moons of misery/ sickling their eye-sockets/ a thousand years of history / in their pockets.” These apparitions are walking to “Croom, Meentogues and Cahirmoyle”, which Hartnett glosses: “Croom: area in Co. Limerick associated with Aindrias Mac Craith (d.1795); also, seat of the last ‘courts’ of Gaelic poetry; also, my birthplace. Meentogues: birthplace of Aodhagán Ó Rathaille. Cahirmoyle: site of the house of John Bourke (fl. 1690), patron of Dáibhí Ó Bruadair.” Bracketed by these calls on his fealty, to place, to people and to poetry, he considered he had no choice but to turn to Irish. Many years later he would write: “…I have poems at hand:/ It’s words I cannot find…” [16]

For all the enmeshments of his situation in history, Hartnett turned to Irish primarily because he heard the words that found him out. That this was due to his particular conception of a poet’s proper duty is both clear and unambiguous – but the consequences of his decision were severe. He moved, with his wife Rosemary and their two children, to a small cottage in Templeglantine, the parish of his grandmother. We find again this wish, to situate himself as a poet among his inherited and chosen people, but if Hartnett expected sustenance and a charge of energy, personal and poetical, from this radical dislocation, it cannot be said that his hopes were fulfilled.

- Working through Irish

His first publication after the move was in both Irish and English, Cúlú Íde and The Retreat of Ita Cagney.[17] The English text is the stronger of the two, a reflection of the fact that Hartnett’s vocabulary and perhaps grasp of syntactical possibilities in Irish lagged behind his highly developed skills in English, but the bilingual reader will also find a hesitancy in the unfolding of ‘Cúlú Íde’ that is not found in the English version. We should observe here that the English is a version of the Irish, and not a translation.

The Templeglantine years were years of hardship, financial and emotional, for all concerned. Of the work that was produced in that small house, it is likely that only Adharca Broic [18] will stand the test of time. Individual poems still have a luminous clarity (for example, ‘Dán do Lara’), but it is doubtful that Hartnett’s work in Irish can be compared in achievement to that of Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill, for instance, or Biddy Jenkinson, Liam Ó Muirthile or Gabriel Rosenstock. This is hardly to denigrate the work but rather serves to make the point that Hartnett’s poems in English are for the most part of a higher order than his poems in Irish – and he was too good a poet, and too honest with himself, not to recognise this.

- Return to English

One might have expected that when he returned to writing in English, he might have taken up where he left off. Instead, his next collection of poems would make use of a form few, if any, have mastered in English, the haiku. Deceptively simple as a form, the haiku relies on triggering a moment of insight in its reader, or a leap into empathetic understanding that is rarely, if ever, an obvious product of the ostensible narrative. Appearing in 1985, the same year as his translations of the great Dáibhí Ó Bruadair, Hartnett’s Inchicore Haiku[19] is a sequence marked by the modesty of its ambitions and of its ostensible subjects. He had always a keen eye for the natural world, but the cumulative impact of this book-length sequence comes from its accumulation of mood and tone – accusing and self-accusing, rueful, sad, disillusioned, occasionally celebratory, the poems mark a quiet, unshowy, return to the notionally abandoned language. No rhetorical flourish, still less an apology for having been away, there is no backward look here, but neither is there the dexterity, the dance with form and thought, that had marked the poems prior to 1975. This is a subdued Hartnett, defeated in his marriage, in retreat from his retreat. He found a new village in Inchicore, and in a sense, a new people with whom he could feel at home, recognised and accepted for himself. Haikus 86 and 87 are instructive:

86

All divided up,

all taught to hate each other.

Are these my people? [20]

87

My dead father shouts

from his eternal Labour:

“These are your people!”[21]

Not for the first time, Hartnett’s self-identification with the poor and powerless gives him his milieu, his chosen audience and his set of subjects, but now the environment is not West Limerick, but a proletarian quarter of the capital city where dreams and promises come to die:

59

The warm dead go by

in mahogany boxes.

“They’re well-housed at last.”[22]

31

All the flats cry out:

“Is there life before dole day?”

The pawnshops snigger.[23]

37

What do bishops take

when the price of bread goes up?

A vow of silence.[24]

Very few of these 87 short poems work as classical haiku – they are mostly too direct and declarative. Then again, the Japanese form relies on linguistic resources in Japanese that do not exist in European languages; perhaps it’s best to think of Hartnett’s haiku as simply short poems in a form approximating to the haiku. The energy of the sequence comes from the juxtaposition of deeply felt personal loneliness with a landscape of low expectations, diminished nature, and disempowerment.

- Fresh Poems, fresh powers and visions

Two years later came the bilingual A Necklace of Wrens,[25] followed by Poems to Younger Women[26] entirely in English. There is a startling return to the power and complexity we might have expected had the poet not turned aside from English in 1975. There are dark energies, some cruelty and vitriol, some tenderness, a measure of hard-won self-knowledge and graceful tributes, but above all there is a powerful surge of life and ambition in the verse making – the “polisher of the complex clause, /wizard of grasses and warlock of birds/midnight-oiled in the metric laws” is back, and with heightened powers. If the prevailing note is a kind of bleak celebration of endurance, nevertheless, there is brio, too, the brio of the toreador, resigned to danger and even to death, not quite courting it but aware that it is factored into the dance.

There had always been a visionary streak in the poems. With The Killing of Dreams[27] (1992), a note that is dramatically and defiantly struck, and which finds perhaps its most perfect expression in ‘A Falling Out’, where the muse figure is not just inspiratrix but also the pitiless withholder of the gift.

She comes from a familiar, homely environment of “overcoats and caps”, of “porter taps”, and battering hobnail boots, from

…the cobbles of the market square,

where toothless penny ballads rasped the air,

there among spanners, scollops, hones, and pikes,

limp Greyhound cabbage, mending-kits for bikes… [28]

the familiar small town territory where “she tricked from me my childish, sacred vow.” The first stanza recapitulates Hartnett’s first stepping out into poetry, and the second rehearses his immersion in the written tradition, the variousness and wild range of what has been prompted by this powerful muse figure. Hartnett offers as her territory a landscape where ultimately all poets are doomed victims of the urge to create: she takes, and then dismisses, out of hand/ the men and women that she most does bless.[29] Sacred capriciousness is one of the qualities Graves attributes to his White Goddess, but where Graves sees the poet as inescapably bound to her rule, heroically stoic, waiting for when the next bright blow may fall, Hartnett, radically, dismisses his muse:

…at dawn I give her bed a gentle shove

and amputate the antennae of love

and watch the river carry her away

into the silence of a senseless bay

where light ignores the facets of her rings

and where the names are not the names of things.[30]

The poem has the air of a poetic suicide note, opening on initiation, closing on repudiation of the gift, and might well have served to close out the poet’s life and work – but perhaps we might read it better as a gambler’s bluff, a kind of dare? In ‘Didactic’ he tells us, bluntly, “the imagination has no limits./ Art has”. [31]

The eye has turned inward, the poet considers whether or not he has outlived his allotted span, ‘… he flounders out of bounds,/ his panacea mocked by a disease/ it was never meant to cure’.[32] Life as a painful site of anguish has been a subdominant theme since Inchicore Haiku. By now it is coming to dominate his imagination, and in poem after poem we find a casting about for release:

Sometimes, with perfect timing, death steps in

and makes the span of living coincide

with the completion of the work on stone,

but, mostly, age insists and the poet cannot see

the very shaping of his chunk of hill

was deed accomplished, mission done.

He never knows that, in the past, he’d won. [33]

For all that, there is something redemptive in the seven-part sequence ‘Mountains, Fall on Us’, a sustained and unflinching set of poems where the suffering man transcends his “list of childish woes”, and faces the hard facts of his life, as man and poet, with stoic acceptance. In the first part we are given a vulnerable figure, a gay man with aesthetic instincts at the mercy of cruel Spanish Catholicism, its ‘jeering trumpets’ redeemed by ‘some kindly waiter’ who ‘kindly dabbed/the distraught mascara from his face’. The second part evokes the poet’s ‘fatal childish dream’ of the life of ease marked out for him; the third section evokes a muse figure whom we might well trace back, to his Grandmother, whose ‘milestones are novenas for the dead’; in the fourth, we find a frank admission that he sits ‘in a soul I do not want’, living ‘this life which has no joy in it’, and in the fifth section the Alexandrian Cavafy is evoked, whose ‘real poems told of real pain’.

This trying on of roles, of lives, of identities, figures the possibilities open to the imagination which has no limits, but is true to the limits of art. In the final two sections, there is a resolute dismissal of all avenues of escape. In the end, he must hang ‘on the great loneliness/of his forgotten cross’, the outcast and thief who ‘asked for mercy and was snubbed by Christ’.

- A man without a people.

In 1991, he translated John of the Cross into Irish.[34] In 1993, he published his lucid translations of Haicéad,[35] and his definitive, nuanced, and sensitive, translation of Aodhagán Ó Rathaille[36] was completed in advance of his death in 1999. Two magisterial poems were left in him; they appeared in Selected and New Poems [37](1994), ‘He’ll to the Moors’; and ‘Sibelius in Silence’. New Poems (1990-1999) added a slight afterthought to the life’s work – followed by the posthumous A Book of Strays in 2002 – but to all intents and purposes, these two long poems wrote the finis.

- The slant towards death and silence

In a bravura keynote address to Éigse Michael Hartnett[38] in 2009, Paul Durcan suggested that Hartnett was possessed of a mediaeval Catholic imagination. ‘He’ll to the Moors’ traces the life of the mystic Ramon Lull, from his beginnings as a troubadour and lover, observer of birds and the ordinary minutiae of the natural world, to the polemicist for Christ who found no rest in the world until he was stoned to death in Tunisia. Durcan argues that this ostensible biography is in fact a species of cloaked autobiography; it traces the arc of Hartnett’s life in parallel to that of its subject, from insouciant celebrant of the small things, through the harrowed fields of desire and disputation until, at the end, he achieves the martyrdom that was always his destiny and his apotheosis. Durcan recruited the poet Michael Coady to his characterisation of Hartnett’s imagination:

‘At heart he was perhaps a classically Irish mix of tidal faith and fatalism – intuitively in touch with a deeply buried Mediterranean impulse in the Irish psyche and native language, but one historically and climatically done down by the fateful alliance of puritan incursions from the east and constant troughs of low pressure from the west…’

[Michael Coady’s Sleeve Notes for the Claddagh Records CD of Hartnett reading his own work]

The CD was issued by Claddagh Records, and in the notes we find Coady’s suggestive claim that “as with all true poets, a mysterious potency of verbal enchantment was at the core of his gift.” The shifts in register, the command of the inscape and outscape of his matter, the baffled and heartbroken humanity of the poem, show a poet in full command of a what is still a considerable gift.

At this point, in the full grip of alcoholism and its attendant furies, Hartnett was much occupied with gathering in the threads of his life, as if rehearsing and preparing an exit he felt drawing inexorably closer. He would write poems yet, short lyrics of uneven quality, but before he came to the desolate child’s cry of ‘A Prayer for Sleep’, the final poem in the 2001 Collected Poems, came the panoramic, cold splendour of ‘Sibelius in Silence’. In this poem, Hartnett revisits the handful of themes that haunted him all his life: the artist’s responsibility to the gift, to tradition and to his own people, and then the struggle to be at home in world and nation, self-doubt and the courage to outlast silence, the quarrel with history, and above all the sense that the lone sensibility cannot hope to overcome the brute weight of the world’s indifference. The chosen extended silence of Sibelius echoes Hartnett’s earlier “I have poems to hand/it’s words I cannot find.” Both poet and composer know that, to be true to the strictures of the art, one must find the discipline and courage to seek and withstand the silence out of which everything comes, into which everything must go.

Hartnett was fascinated by the elected silence the composer sought, until he emerged with what he considered the voice itself of the place itself, speaking itself:

I offer you here cold, pure water –

as against the ten-course tone poems,

the indigestible Mahlerian feasts;

as against the cocktails; many hues,

all liquors crammed in one glass –

pure, cold water is what I offer.

(Collected Poems p. 227)

The question is to what degree Hartnett conflates himself with Sibelius. Is Sibelius a mask he put on in order to confront himself, or is the poem intended as an homage, of one troubled soul acknowledging unresolvable ambiguity, in this question that can only be answered with “it is both and neither”.

When we consider the place of the poem in Hartnett’s long contribution to poetry, there is something heartbreakingly final about the concluding lines to what is, in effect, Hartnett’s farewell to poetry:

…that which was part of me has not left me yet –

however etherialised, I still know when it’s there.

I get up at odd hours of the night

or snap from a doze deep in a chair;

I shuffle to the radio, switch on the set,

and pluck, as I did before, Finlandia out of the air.

(p. 228)

He is far from Castletown house, and the plangent evocation of Tortellier; far, too, from the ballads and company of Maiden Street pubs, far from the poems of his Gaelic predecessors, from Lorca, from the austerity of Pasternak and the dark meditations of John of the Cross. One last great effort, a tour de force, and he lays down his pen, as “Into my room across my music-sheets/ sail black swans on blacker rivers”.

[1] Dennis O’Driscoll, The Outnumbered Poet (Loughcrew: The Gallery Press, 2013, P. 199

[2] Michael Hartnett, Collected Poems, ed. Peter Fallon (Loughcrew: The Gallery Press, 2001) p. 139

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid., p.33.

[5] Ibid.,p.3.

[6] Michael Hartnett, Anatomy of a Cliché (Dublin: The Dolmen Press, 1968)

[7] Ibid., p.17.

[8] Michael Smith, ‘Remembering Michael Hartnett’ (Dublin: The Irish Times, 16th February 2009)

[9] Michael Hartnett, A Farewell to English (Loughcrew: The Gallery Press, 1975)

[10] Ibid., p.27.

[11] Ibid., p.26.

[12] Ibid., p.34.

[13] Ibid., p.35.

[14] Ibid., p.30.

[15] Ibid.

[16] ‘Impasse’, Collected Poems, p.194

[17] Michael Hartnett, The Retreat of Ita Cagney/Cúlú Ide, (Curragh, Kildare: The Goldsmith Press, 1975)

[18] Michael Hartnett, Adharca Broic (Loughcrew: The Gallery Press, 1978)

[19] Michael Hartnett, Inchicore Haiku (Dublin: Raven Arts Press, 1985)

[20] Ibid., p.35.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid., p.26.

[23] Ibid., p.17.

[24] Ibid., p.19.

[25] Michael Hartnett, A Necklace of Wrens: Poems in Irish and English (Loughcrew: The Gallery Press, 1987)

[26] Michael Hartnett, Poems to Younger Women (Loughcrew: The Gallery Press, 1988)

[27] Michael Hartnett, The Killing of Dreams (Loughcrew: The Gallery Press, 1992)

[28] Ibid., p. 16.

[29] Ibid., p.17.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid., p.26.

[32] Ibid., p.26-27.

[33] Ibid., p.27.

[34] Michael Hartnett, Dánta Naomh Eoin na Croise (Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim, 1991)

[35] Michael Hartnett, Haicéad (Loughcrew: The Gallery Press, 1993)

[36] Michael Hartnett, Ó Rathaille: The Poems of Aodhagán Ó Rathaille (Loughcrew: The Gallery Press, 1999)

[37] Michael Hartnett, Selected and New Poems, (Loughcrew: The Gallery Press, 1994

[38] Paul Durcan, ‘He’ll to the Moors’ (originally given as ‘Michael Hartnett’s Way of the Cross – the Final Quest’, keynote address at Eigse Michael Hartnett, Newcastle West, April 2009).

About the Author:

Theo Dorgan is an Irish poet, writer and lecturer, translator, librettist and documentary screenwriter. He lives in Dublin with his wife, the poet and playwright Paula Meehan.

Dorgan was born in Cork in 1953 and was educated in North Monastery School. He completed a BA in English and philosophy and an MA in English at University College Cork, after which he tutored and lectured at that university, while simultaneously being literature officer at the Triskel Arts Centre in Cork.

After Dorgan’s first two poetry collections, The Ordinary House of Love and Rosa Mundi, went out of print, Dedalus Press reissued these two titles in a single volume, What This Earth Cost Us. He has also published selected poems in Italian, La Case ai Margini del Mundo (Faenza, Moby Dick, 1999).

He has edited The Great Book of Ireland (with Gene Lambert, 1991); Revising the Rising (with Máirín Ní Dhonnachadha, 1991); Irish Poetry Since Kavanagh (Dublin, Four Courts Press, 1996); Watching the River Flow (with Noel Duffy, Dublin, Poetry Ireland/Éigse Éireann, 1999); The Great Book of Gaelic (with Malcolm Maclean, Edinburgh, Canongate, 2002); and The Book of Uncommon Prayer (Dublin, Penguin Ireland, 2007).

He has been the series editor of the European Poetry Translation Network publications and director of the collective translation seminars from which the books arose.

A former director of Poetry Ireland, Dorgan has worked as a broadcaster of literary programmes on both radio and television. He was the presenter of Poetry Now on RTÉ Radio 1, and later for RTÉ Television’s books programme, Imprint. He was the scriptwriter for the television documentary series Hidden Treasures. His Jason and the Argonauts, set to music by Howard Goodall, was commissioned by and premiered at the Royal Albert Hall in London in 2004. A series of text pieces by Dorgan feature in the dance musical Riverdance; he was specially commissioned to create them for the theatrical show. His songs have been recorded by a number of musicians, including Alan Stivell, Jimmy Crowley and Cormac Breathnach.

Dorgan was awarded the Listowel Prize for Poetry in 1992 and the O’Shaughnessy Prize for Irish Poetry in 2010. A member of Aosdána, he was appointed as a member of the Arts Council (An Chomhairle Ealaíon) from 2003 to 2008. He also served on the board of Cork European Capital of Culture 2005.

He was awarded the 2015 Poetry Now Award for Nine Bright Shiners.

You must be logged in to post a comment.