I became a serious walker in 2009! For several years before that, I had been severely hampered by arthritis in my left hip. After years of being told that I was too young for a hip replacement, I had the operation in Croom in November 2008. The operation was a complete ‘textbook’ success, according to my very favourite orthopaedic surgeon, Eric Masterson.

The operation gave me a new lease of life and, whereas up to that time walking was a painful chore, now I felt energised and ready to explore. Since then, I have loved to walk – in Summer especially or when the scales tip 215 lbs! I head off, and a trek of twenty kilometres is not unusual. I have visited all my local villages on foot, in their turn, Rathkeale, Ballingarry, Castlemahon, and Kilmeedy. In recent years, since Mary moved to Glenroe, I have gloried in rediscovering the Ballyhouras, and whether it is a trek over Sheehy’s Hill or climbing up to Castlegale or the more arduous Darragh Loop, the trails and loops have brought me great joy.

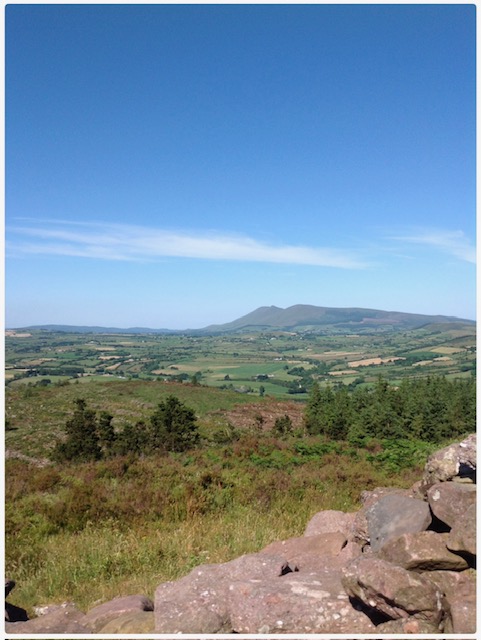

Castlegale is a great parish reference point. Looking south, it dominates the landscape. I remember my mother telling me that in the landlord days of rents and rackrents, the Gascoignes of Castle Oliver placed a flag on the cairn at the summit of Castlegale to let tenants know their rents were due. Today, Castlegale is central to some of the many amazing trekking loops which have been developed in recent years by the Ballyhoura Bears and by Ballyhoura Development. The walk to the summit from Darragh takes you through the beautiful ancient pathway, the Gabhairín Rua.

The Ballyhoura Region itself is a truly mythical landscape – Seefin, Glenosheen, Glenanaar, the Black Dyke, Ardpatrick – these high places carry evidence of cairns or old monastic ruins, a strange mixture of the ancient battles between the old dispensation and the new. And up in these hills, you come across strange sights as you ramble. I’ve come across Army Rangers perfecting their orienteering skills, in full combat gear, traversing this God-forsaken wilderness on their way to rendezvous with other members of their regiment.

The name Seefin (Suí Finn) translates as the ‘Seat of Fionn (Mac Cumhaill)’. It is so named because, according to tradition, Fionn and his Fianna rested here on their hunting excursions to the other sacred places, like Knockainey (Cnoc Áine), and our other sacred Limerick hill, Knockfierna (Cnoc Fírinne). Down below Seefin, the highest point in the Ballyhouras, is the quaint Palatine village of Glenosheen, named in honour of Óisin, the son of Fionn. The village is famous as one of the settlements established by a colony of Irish Palatines, German Protestant refugees, who settled there in the early 18th century. Some of their historic houses and family names, like Switzer, Teskey, Ruttle, Young, Sparling, Wolf, Baker, Weekes and the Steepes, are still evident today. Their main settlement in Limerick was Rathkeale, where they used their expertise to bolster the emerging linen and flax industry in the area. Today, in Rathkeale, there is a fabulous Palatine Museum at the trailhead for the West Limerick Greenway dedicated to their memory.

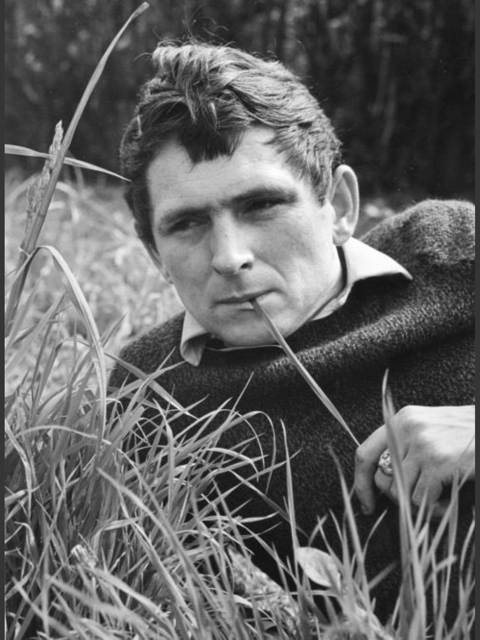

Glenosheen is also remembered as the home of the famous Joyce Brothers, Patrick Weston Joyce and Robert Weston Joyce. Both were born in Keale in the parish of Glenroe, Ballyorgan, and the family later moved to Glenosheen. Both brothers taught in the old National School in Glenroe. Patrick would you believe it, began his teaching career there at the age of eighteen in 1845, during the height of the Famine. He had been educated in numerous well-known and well-endowed Hedge Schools in Kilfinane, Kilmallock and Mitchelstown by the very best travelling scholars. He taught in a number of schools, including the High School Clonmel, before eventually going on to have a distinguished career at Trinity College, Dublin. Here, he made a name for himself as a historian, a linguist, and a significant collector of Irish folk music and traditional airs. He held influential positions in the Irish education system and authored numerous works on Irish history, place names, and the Irish language. His efforts helped preserve a vast amount of Irish cultural heritage. Indeed, the first book I ever read when I was in Fifth Class in Primary School, having recently graduated from comics, was his fabulous collection of old legends, Old Celtic Romances, telling the almost forgotten tales of Fionn and Óisín, Cúchulainn and Diarmuid agus Gráinne.

His brother, Robert Dwyer Joyce (1830 – 1883), was no less famous and distinguished. He was a medical doctor who achieved renown as a writer, poet, and song lyricist. He was associated with the Fenian movement (1867) and wrote popular ballads, including ‘The Wind that Shakes the Barley’ and ‘The Boys of Wexford’. His literary contributions often centred on Irish themes and history. He also spent time in the United States, where he was well-regarded.

Further west, and nearer to home, I love trekking on the slopes of Knockfierna, near Ballingarry in County Limerick. This place is famous for its poignant Famine Village history, where, during Famine times, over a thousand people lived in makeshift homes on the side of the hill. It is a unique experience to walk among the ruins of the semi-restored cottages, shebeens, and Rambling House. Today, thanks to the work of Pat O’Donovan and his restoration group, the Knockfierna Famine Trail leads visitors past these preserved cottage ruins, garden plots, and other memorials, offering a moving, reflective experience amidst stunning views of the Golden Vale. The whole experience showcases both Irish resilience and the devastating impact of the famine.

Another one of my favourite rambles is in The Castle Demesne in Newcastle West, Co. Limerick, especially when rain threatens. This beautiful 100+ acre sylvan parkland with walking trails, playgrounds, and picnic spots, surrounding the historic Desmond Castle and its Banqueting Hall in the town square, is heavily wooded, and there is great shade from wind and blustery showers. It is an amazing family-friendly amenity right by the town centre, and it is easily connected to the scenic Limerick Greenway. This historic site, once home to the powerful Earls of Desmond, including the famous third Earl of Desmond, Gearóid Íarla, features centuries of history with stunning parklands for leisurely strolls, rich flora and fauna, and is a central part of Newcastle West’s heritage. Legend has it that Gearóid disappeared in mysterious circumstances in 1398 while walking in the Demesne grounds, and today he is fabled to live beneath the waters of Lough Gur, near Bruff, over whose waters he is said to appear once every seven years, riding his white steed.

I am also very lucky to have the fabulous Limerick Greenway within striking distance. I have to say it is becoming more and more dangerous walking on minor country roads; such is the total absence of courtesy, and speed limits are totally ignored. Thankfully, I now have The Greenway, which was built along the former Limerick to Tralee railway line, and after many years of development, is now a state-of-the-art off-road cycling and walking route that can be accessed through numerous entry points. The Greenway weaves its way through West Limerick’s traditional agricultural landscape, starting in Rathkeale, on through Ardagh, Newcastle West, Barnagh, Templeglantine and finishing in Abbeyfeale, passing through Tullig Wood, with its mature, serene woodland and native trees, providing a restful calm and balm for all travellers.

Walking by the sea offers therapeutic benefits, combining gentle exercise with stunning views. There are other benefits, such as stress relief and connecting with nature. Whether one sets out on a relaxing stroll on sandy beaches or undertakes the more vigorous coastal path hikes, one can be enriched by the bracing fresh air, the sound of waves, the prospect of some whale spotting and the occasional sea wreck. It’s a popular way to enjoy leisure time, explore scenic routes, and find peace, like the beautiful hike out past the Diamond Rocks in Kilkee and up Dunlicky or George’s Head.

One of our favourites is the Ballycotton Cliff Walk, definitely a podcast-free ramble, with majestic sea vistas looking out over the final resting place of the doomed Lusitania. No trip to Ballycotton is complete without a rewarding visit to nearby Ballymaloe for a coffee and delicacies! Or when in Ardmore, head out past the Cliff House Hotel and the ruins of St. Declan’s Hermitage and Well and enjoy the stunning sea views and ramble back towards the quaint little seaside town via the majestic Round Tower. It is a stunning looped coastal trail offering beautiful sea views, historical sites, and the chance to spot the Samson crane barge wreck in its lonely final resting place.

Since retirement, we have been making frequent visits to the Canary Islands and especially, Puerto Rico in Gran Canaria. This place, as opposed to Puerto del Carmen, is challenging enough and rambles in the early morning or after four in the evening are recommended. Kate and I have been coming here now for the past twenty years, and each visit uncovers new delights, and improved pathways, steps and roadways. Our favourite walk is the Cliff Walk between Puerto Rico Beach and the man-made Amadores Playa. This is an easy ramble and often a preamble to more strenuous excursions.

We invariably book accommodation on the lower level. Corona Cedral would be our favourite place of all, but we have also stayed in Monte Verde, Letitia del Mar, Maracaibo, and Rio Piedras, with its terracotta terraces overlooking the beach. All these are very central – near the two main Shopping Centres and the beach and its many restaurants.

The only drawback I find with Puerto Rico is its distance from the airport – approximately 40 kilometres. However, Gran Canaria has a first-class public transport system and once free of arrivals and the terminal building, you can go to the bus terminal and get the 91 bus to Puerto Rico for €5.45 – as opposed to €70 for a taxi. Alternatively, Ryanair and others provide reasonably priced shuttle services to and from the airport.

As one becomes familiar with the area, one becomes more confident in foraging out new trails, loops and challenging treks. The one thing to notice is that there are steps everywhere linking the various levels. The local authority has done fabulous work in the past five years, building a series of steps from the beach to the high point near Puerto Azul apartments. In all, there are 756 steps in this series – individually counted! Depending on your exertions, you can decide to descend the 756 or take on the more daunting challenge and ascend – or even decide to work both into your evening ramble!

Evening walks usually involve thoughts of home and the girls, Maeve, Anna, Muireann and, of course, Mary, Mike and Don. There is a tree on one of the summits which I always associate with them. It grows in the centre of a roundabout down the road from the Europa Centre, and very near the Balcon de Amadores apartment complex, and invariably, when I get this far, I usually give them a ring to check how things are, and to check on Knockaderry’s, Clanna Gael Fontenoy’s, or Limerick’s progress in the Championship.

On Lanzarote, ‘El Varadero de la Tinosa’, is the original village of what is now the thriving Old Town centre of Puerto del Carmen. Today, it is still a centre for fishing, and there is a very strong seafaring tradition in the area. The beautiful little church sits just feet from the water’s edge, facing the little fishing port. Today, it is a centre for tourist trips, and there is a regular hourly ferry plying between the port and Puerto Calero – the destination for one of my favourite rambles. Leaving Casa Roja restaurant, we walk to the end of the boardwalk and to the newly paved area at the top. There are lovely views out to sea and many viewing areas along this stretch of the walk.

We walk south-east along the coast. The distance is 2.2 kms. approx and the walk, taken at a nice brisk pace, will take you about thirty minutes. The path now changes to a dirt track, and there is evidence of the remnants of an ancient stone road which runs above a small cliff that permits a glimpse from above of the intertidal area, its coves and small inlets.

We arrive at ‘The Barranco (ravine) del Quiquere’, of interest because its volcanic sides contain engravings from the indigenous world of the island of Lanzarote. We can get a close look at them by taking the track just 50 metres to the north on the right side of the ravine as you walk from Puerto del Carmen.

The views of the sea and islands of Lobos Island and Fuerteventura to the south enhance the beauty of the landscape in this area, and eventually we arrive at the newly man-made marina of Puerto Calero. This beautiful port and marina are a fitting ending after our cliff walk, and a ramble around the upmarket shops and outlet stores is highly recommended. There are also numerous high-quality restaurants and at least two hotels nearby. Puerto Calero is renowned as a headquarters for some round-the-world yacht crews, and after a brief look around, you will see why.

Ralph Waldo Emerson has laid down my walking ground rules: “Few people know how to take a walk. The qualifications are endurance, plain clothes, old shoes, an eye for nature, good humour, vast curiosity, good speech, good silence, and nothing too much.” I am also reminded that numerous other poets, philosophers and novelists have also wandered and wondered. Kierkegaard did so in the countryside near Copenhagen and suggested that it might be good for his niece, Jette, to do likewise. Prompting her in 1847, he came up with a notion I repeat on my own travels: “Above all, do not lose your desire to walk. I walk myself into a state of well-being and walk away from every illness. I have walked myself into my best thoughts, and I know of no thought so burdensome that one cannot walk away from it” (A Letter to Henrietta Lund from Søren Kierkegaard, 1847, trans. Henrik Rosenmeier, 1978).

I haven’t read many of HG Wells’ novels, but there’s another mantra from one of the non-fiction works, Modern Utopia, that I’ll happily take to my grave: “There will be many footpaths in Utopia.” And whether I’m rambling in the Ballyhouras or Ballycotton or above Ashford on the Cob Road or the hills above Bormes les Mimosa, in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur Region, southeastern France, or in Puerto Rico, my favourite nugget of wisdom is, of course, T.S. Eliot’s evocative words from The Waste Land (1922), surely one of the most beautiful poetic lines ever written, “In the mountains, there you feel free.”

In conclusion, I am often reminded of the lovely Latin phrase, Solvitur ambulando – ‘it is solved by walking’ – sometimes attributed to St. Jerome or Diogenes, or St. Augustine, maybe even Thoreau or Chatwin, inter alios…..

So, put your best foot forward!

You must be logged in to post a comment.