POLONIUS

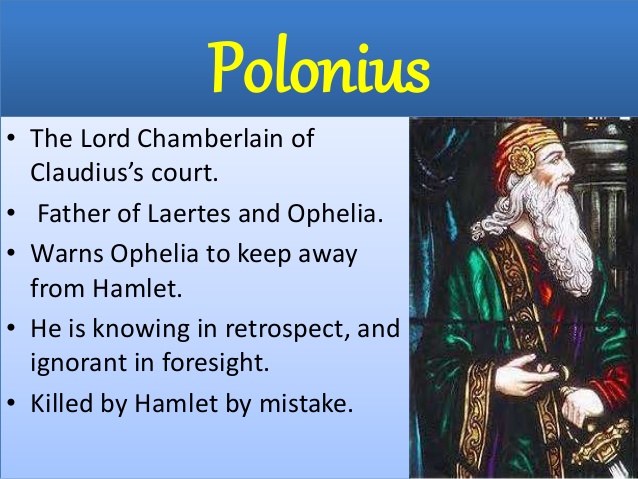

There must be a strong temptation for actors to play Polonius as a foolish old man, the comic victim of Hamlet’s sharp wit, even as a buffoon. Samuel Johnson’s account of the character is worth repeating for its emphasis on some important features:

‘Polonius is a man bred in courts, exercised in business, stored with observation, confident in his knowledge, proud of his eloquence, and declining into dotage. His mode of oratory is truly represented as designed to ridicule the practice of those times, of prefaces that made no introduction, and of method that embarrassed rather than explained. This part of his character is accidental, the rest is natural. Such a man is positive and confident, because be knows that his mind was once strong, and knows not that it is become weak. Such a man excels in general principles, but fails in the particular application… while he depends upon his repositories of knowledge, he utters weighty sentences, and gives useful counsel; but as the mind in its enfeebled state cannot be kept long busy and intent, the old man is subject to sudden dereliction of his faculties, he loses the order of his ideas, and entangles himself in his own thoughts, till he recovers the leading principle, and falls again into his former train. The, idea of dotage encroaching upon wisdom, will solve all the phenomena of the character of Polonius’.

There is no doubt that the aspects of the character to which Johnson draws attention can be illustrated from the play. Hamlet sees him as Johnson does, as one of ‘those tedious old fools’, and ‘that great baby……not yet out of his swaddling clothes’. There are, too, the longwindedness, the impressive openings that meander into fatuity, and sometimes jolt into embarrassing frankness, as in the business of communicating his diagnosis of Hamlet’s madness’ (11,ii,92-165). He wins easy laughs, sees himself as something of a sage, if an absentminded one. He himself reminds us of another of his powers, that of detection: ‘I will find where truth is hid, though it were hid indeed / within the centre’ (11,ii,158). He gets three character testimonials in the course of the play. One is solicited, and is from Claudius, who describes him as ‘a man faithful and honourable’. Two are unsolicited. Claudius declares that the throne of Denmark is at his command, and Gertrude calls him ‘the unseen good old man’ after his death. This epitaph contrasts oddly with Hamlets reference to the ‘wretched, rash, intruding fool’, who was in life ‘a foolish prating knave’.

Johnson’s account is accurate enough as far as it goes, but neither his nor many of the other popular interpretations of the character do justice to the darker and more sinister sides of his personality. What is attractive about Polonius belongs to the outward man, who can claim a certain indulgence for his foibles. But beneath the mask lurks a treacherous plotter, with a gravely retarded moral sense. He trusts his children so little that he sets spies on them, and he dies as a spy in the Queen’s bedroom. He cannot see his fellow-human beings as other than puppets, and has no respect for privacy. He forces Ophelia against her better interests to act in his nasty drama involving Hamlet, and manipulates her like a doll: ‘Ophelia, walk you here…read on the book’. He pries into other people’s lives without apology or embarrassment. He can sacrifice his daughter’s feelings and her reputation to his own limited, self-centred concerns, and his choice of words to describe his procedures underlines their, and his, nastiness: ‘At such a time. I’ll loose my daughter to him’ (11,ii, 165). He cynically misunderstands Hamlet’s attention to Ophelia, and debases the office of Chancellor by converting it to a spying agency. His insensitive intrusion into the Hamlet-Gertrude relationship shows his blindness to the intense feeling that many underline such relationships, as well as his lack of respect for the privacy that should surround them. He will have Gertrude provoke Hamlet to a violent outburst: ‘Let his Queen-mother all alone entreat him / To show his grief; let her be round with him’. He even takes a perverse delight in anticipating what he feels will be almost an entertaining spectacle for him, but his final instructions to Gertrude, in which he urges her to be ‘round’ with Hamlet, shows no understanding of the kind of response such behaviour on her part will arouse. It is ironical that he should meet his death in a production staged by himself, and with himself as director. We remember his earlier lines:

I did enact Julius Caesar. I was killed i ‘the Capitol.

Brutus kill’d me…(111,ii,101)

LAERTES

Laertes functions as a foil to Hamlet. He is a conventional revenge hero, and consequently represents a standard of measurement for Hamlet. Like his father, he is given to conventional moralising, giving Ophelia some serious and misleading advice on her relationship with Hamlet, just as Polonius will do. Her quiet response anticipates the course his life will take. He is one of those who can show others the right way, but who will not follow it himself, who ‘recks not his own rede’. On his return to Denmark after his father’s death, his decisive action contrasts with Hamlet’s indecision. He has enough courage to face Claudius alone, but his words are those of a melodramatic villain rather than of a wronged son and brother:

To hell, allegiance! Vows, to the blackest devil!

Conscience and grace, to the profoundest pit!

I dare damnation…(IV,v,117))

Worse is to follow. Laertes forgets all the edifying moral principles he so freely shared with Ophelia when he expresses a willingness to cut Hamlet’s throat ‘in the church’. Even more damaging is the fact that he has come to Denmark with the means of practising treachery on an enemy (‘I bought an unction of a mountebank). He is able to add a poisoned weapon to Claudius’ plan to use an unbated foil. Hamlet can be emotionally unstable, but is not morally unstable; Laertes is emotionally stable enough, but morally quite unstable. His interview with Claudius brings one’s mind back to the advice tendered to him by Polonius:

This above all – to thine own self be true

And it must follow, as the night the day

Thou canst not then be false to any man…1,iii,77).

In the event, he proves totally untrue to any decent conception he may have of himself. The king has little difficulty in exploiting his weak moral sense. He employs flattery, a false show of sympathy, a clever challenge to pride, ‘what would you undertake / To show yourself in deed your father’s son / More than in words’. Laertes is blackmailed into a treacherous partnership with Claudius, which he lacks the moral strength to break. His shallowness is underlined when, before the fencing-match, he repents too late and only when his own life is ebbing away. He does, however, make sure that Claudius is trapped (‘The king, the king’s to blame’).

OPHELIA

Character-studies of Ophelia are liable to sound rather tame, and can easily lapse into sentimentality. There is a pathetic beauty about her death, and a charming innocence about her activities during life. She is, as her father says, ‘a green girl’, childlike, inexperienced, frightened by Hamlet’s odd behaviour, totally obedient to her father. She is, of course, one of the classic examples of the innocent sufferer in tragedy, the pathetic victim of a process set in motion by forces beyond her control and over whose course she has no influence. She pays the penalty for the crimes of others. In many tragedies there is an appalling disproportion between the offences committed by the participants and the sufferings they endure. In Ophelia’s case one might go even further, since she is the guiltless victim of the evil that surrounds her, and must endure bereavement and die in madness as a consequence. In the case of Polonius and Laertes there is at least the satisfaction of being able to rationalise their deaths as the outcome of crime or rashness. Laertes sees some justice in his fate, and Hamlet finds an absurd appropriateness in that of Polonius. But no such ‘meaning’ can be extracted from what happens to Ophelia.

For a long time critics could find little enough meaning in Hamlet’s treatment of her in the ‘nunnery scene’ (111,I,90-150). There is, of course, the obvious general point that Gertrude’s sin has had a profound effect on Hamlet’s attitude to all women (‘Frailty thy name is woman’) and that his disgust at his mother taints his mind against even the innocent Ophelia. Elements of this are present in the scene (‘I say we will have no more marriage; those that are married already, all but one shall live…’). In one of the most influential observations on the play, Dover Wilson, the renowned Shakespearean scholar, argued that at 11,ii,160, Hamlet overhears the King and Polonius as they plan the encounter between Ophelia and himself, and that his anger against Ophelia is largely inspired by his view of her in the role of fellow-conspirator with Claudius and Polonius against him. This suggestion would also help to make some sense of Hamlet’s odd and insulting exchanges with Polonius in 11,ii 174 beginning ‘Excellent well, you are a fishmonger’ (a slang term for our word pimp) which otherwise seems inexplicable, at least in this contest. If Shakespeare did not really arrange matters as Dover Wilson thinks he did, then perhaps he ought to have!

However, as we have discussed in class, an alternative theory is that yes he is aware that she is being used by ‘the lawful espials’ in the court and he wants to save her further hurt and so pushes her away for her own safety. However, like many other of his plans, this one does not work either!

Sample Answer:

‘Ophelia is the guiltless victim of the evil that surrounds her, and must endure bereavement and die in madness as a consequence’ Discuss.

Ophelia is isolated in a man’s world. She is used in many conspiracies against Hamlet. She is not cherished for herself, except when she is grieved over:

I lov’d Ophelia. Forty thousand brothers could not make up my sum.

Laertes and Polonius forbid her to develop a relationship with Hamlet because of their resentment towards him. Laertes suggests to his sister that her marriage to Hamlet would endanger the Danish state:

For on his choice depends the safety and health of this whole state.

What is a sensitive young woman to make of this? Yet Gertrude declares at Ophelia’s funeral:

I hop’d thou shouldst have been my Hamlet’s wife.

Laertes gets it wrong. But what effect does this interference have on the emotional state of a young woman who ‘sucked the honey of his music vows’? After all it turns out that Hamlet has treated her sweetly and showered gifts on her with ‘words of so sweet breath compos’d, as made the things more rich.’

Laertes imputes motives of lust to Hamlet even though he is just back from his studies at the famous reformation university of Wittenberg and has shown a profound sincerity of grief for his father:

A toy in blood; a violet in the youth of primy nature, forward, not permanent.

Her brother teaches her to distrust Hamlet’s advances and fear love:

Your chaste treasure open to his unmaster’d importunity.

Fear it, Ophelia, fear it.

Polonius forcefully dismisses her as ‘a green girl’. Hamlet is portrayed as a seductive opportunist, using his charm as ‘springs to catch woodcocks!’ She obediently denies herself her one means of happiness.

In the Nunnery Scene she is exploited in a game of espionage against Hamlet. The Queen is looking for an explanation of Hamlet’s ‘wildness’:

I do wish that your good beauties be the happy cause of Hamlet’s wildness.

She is, therefore, a pawn in a fatal game of intrigue, believing as the Queen does that in the accidental meeting, ‘her virtues’ may bring back Hamlet’s ‘wonted ways’ or sanity. But in truth this is only a pretext to ‘sugar o’er the devil’ and assist Hamlet’s two enemies. Suspecting the worst, Hamlet abuses Ophelia terribly in order to intimidate the King:

Get thee to a nunnery! Why wouldst thou be a breeder of sinners?

Hamlet ironically echoes Claudius’ guilty remark about the ‘harlot’s cheek, beautied with plastering art’ – as if he had overheard their plans to uncover his mask of madness:

I have heard of your paintings too.

She is devastated for both of them: ‘Oh help him you sweet heavens’ and she refers to ‘sweet bells jangled’. Her despair for herself follows swiftly:

‘Ands I, of ladies most deject and wretched’.

When Hamlet leaves, she seems to break down in her speech, ending with:

‘Oh woe is me / to have seen what I have seen, see what I see’.

Ophelia’s world is beginning to collapse. So far in her life, she has been under the continual direction of three men: her father, her brother and her lover. Her brother has gone to Paris. Her lover is insane and abuses her. When her father dies at the hands of the man she loves, there is no one to direct her. In Act I, Scene iii, Polonius told her to ‘think yourself a baby’, and tells her to stop believing what Hamlet has said and believe what he says instead. She succumbed to this and is now, therefore, totally isolated. Ophelia has never had to make her own mind up and has been dissuaded from doing so. It might be fair to say that she does not have a mind of her own. What happens when that infant mind is left to fend with the loss of everyone who is important to her?

This impression of Ophelia is strengthened, I think, in the Play Scene. Hamlet embarrasses and confuses her publicly. She is almost completely incapable of responding. She has never been spoken to like this before and does not have the personality to cope:

That’s a fair thought to lie between maids’ legs.

It is important to consider what Ophelia’s songs can tell us about her state of mind and what Ophelia’s madness adds to our understanding of madness in the play. At the beginning of Act IV, Scene v, the unnamed gentleman tells us that Ophelia is mad. At this point the Queen, full of her own troubles refuses to see Ophelia. Her isolation is complete. The gentleman says she speaks much of her father and that much of her speech is meaningless, but its chaotic state makes those who hear it try to make sense of it. They are amazed by her speech and make the words fit their own interpretation. (Very little has changed over the intervening four hundred years!). This statement seems to be crucial to understanding how madness is presented in this play. When Hamlet and Ophelia are thought to be insane, their observers try to interpret the reasons for their insanity. The reasons they come up with always reflect the preoccupations of the observers.

In the case of Hamlet, Claudius thinks he has a deep hidden secret since he himself has a hidden secret:

There’s something in his soul o’er which his melancholy sits on brood.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern think that Hamlet’s ambition is the cause of his madness since they themselves are ambitious. Similarly with Ophelia, Laertes thinks she is trying to tell him to take revenge for her father because this is a course he has already decided on:

By heaven, thy madness shall be paid by weight.

Therefore, it can be said that in Hamlet, madness is a mirror.

A close analysis of the songs Ophelia sings can also be enlightening. She sings three songs to the Queen in Act IV, Scene v, and two more later in the scene after Laertes arrives. Her first song is about an absent lover, the second is probably a lament for her father, while the third song, ‘Tomorrow is St. Valentine’s Day’, is a story of how a young girl is duped into sleeping with a man who promises to marry her and doesn’t. The first two don’t create much of a problem: after all, she has an absent lover and a dead dad! The third song, more bawdy, is a little trickier. Hamlet has not been unfaithful to Ophelia; in fact the opposite is true. He has, however, been very unpleasant towards her and this has obviously disturbed her. She may be mourning the loss of her virginity, for she may have made love to Hamlet but the bottom line is that we don’t know enough to make a definite judgement.

It is plausible, going on the evidence of these five songs, to assume that Ophelia’s madness was caused by the death of her father, the loss of Hamlet and her confusion at his sarcastic remarks to her. She probably feels a deep sense of loss for his love and companionship. It is clear that by the end of Act IV that Ophelia had attained two dark finalities that Hamlet had either faked or at least meditated on: madness and suicide. One bizarre aspect of this story is that the Queen seems to be aware of Ophelia’s mental state yet she does nothing to save her.

Ophelia dies near the ‘weeping willow’, which suggests that she died of grief. The brook is also described as a ‘weeping brook’. Another thing to note are the other plants that are mentioned. She has been associated with flowers throughout the play. She’s an ‘infant of the spring’ in Act I, Scene ii and in Act IV, Scene v, Laertes describes her as a ‘rose of May’, where she also hands out flowers to the Court. At her funeral, Laertes imagines violets springing from her grave and the Queen strews her grave with flowers, which may signify her innocence, beauty, youth and fragility.

In Act IV though the flowers are weeds: crow-flowers, nettles, long-purples and daisies. Perhaps these are a symbol of Ophelia’s decline, madness, or her disillusionment with the Danish Court. Indeed, it has been suggested that it was in fact this Court that killed her. She was, in effect, ‘a guiltless victim of the evil that surrounds her’.

Great analysis, very useful for anyone studying Hamlet.

LikeLike

Thank you Ryan – have been using those notes for many years as basis for Senior English classes – check out the other related Hamlet posts also.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I definitely will. I have taught Hamlet to senior classes in the past and found that they have difficulty with the complex issues in the play. Good notes are essential for their understanding. Thank you..

LikeLike

It is truly a fascinating masterpiece – glad you liked the posts – we gave to stick together!

LikeLiked by 1 person