Camas is a small nondescript townland nestling in the shadow of the nearby village of Ratheenagh in rural West Limerick. In the Author’s Notes to his Collected Poems (2001), Michael Hartnett tells us that, ‘Camas is a townland five miles south of Newcastle West in County Limerick where I spent most of my childhood’. This local townland proved to be a central element in his early development. There, the young impressionable Hartnett was influenced by his people, particularly his grandmother, Bridget Halpin, and their customs and way of life. Indeed, in the mid-70s, when he tired of the Dublin literary milieu, it was to this same rural West Limerick bastion, nearby Glendarragh in Templeglantine, still steeped in Irish music and culture, to which he returned. It was to this place he came to escape Dublin’s incestuous stranglehold and perhaps to write a new chapter “out foreign in ‘Glantine”.

There are up to fifteen poems by Hartnett which could be considered ‘Camas Poems’. These memory poems are all based on his childhood recollections of those happy times in his grandmother’s kitchen. Students of Hartnett’s poetry should consider studying ‘A Small Farm’ (Collected Poems 15) as one of a series of memory poems that he wrote celebrating his grandmother, Bridget Halpin and the townland of Camas where she lived. The most obvious of these Camas Poems is ‘Death of an Irishwoman’ (Collected Poems 139), which he wrote on the passing of his grandmother in 1965. Others include ‘For My Grandmother Bridget Halpin’ (Collected Poems 52), and ‘Mrs Halpin and the Lightning’ Collected Poems 138) and of course ‘An Múince Dreoilíní ‘/ ‘A Necklace of Wrens’ (A Necklace of Wrens 18), a quintessential memory poem from childhood.

Hartnett’s early poetry creates a delicate balance between description and abstraction, the actual and the figurative. The poem ‘A Small Farm’, the first poem of the Collected Poems (2001), a memory poem dating from Hartnett’s teenage years, establishes this. Abstractions, clichés, their representation through language, and the moment where these are drawn into focus, made specific and immediate, are central. The setting of the ‘small farm’ is described en abstracto: ‘All the perversions of the soul / I learnt on a small farm’ (15). In contrast to other contemporary representations of Irish farm homesteads, most obviously Kavanagh’s ‘Inniskeen’, and Heaney’s ‘Anahorish’, there is no naming of place here. The picture of the farm is rather etched out in generalisation and aphorism, and through the accordant clichés of petty hatred and ignorance, ‘how to do the neighbours harm / by magic, how to hate’ (15), before Hartnett brings the glass into focus, employing idiosyncratic detail which establishes the world of the poem itself. In this way, Hartnett’s particular subjectivity, his way of seeing, is established. It would become his poetic currency:

Here were rosary beads,

a bleeding face,

the glinting doors that did encase their cutler needs,

their plates, their knives, the cracked calendars of their lives. (15)

In the final stanza, Hartnett makes an explicit link between his awakening as a perceiver of social interactions and moments of poetic beauty, with a growing knowledge and identification with the natural world:

I was abandoned to their tragedies and began to count the birds,

to deduce secrets in the kitchen cold,

and to avoid among my nameless weeds

the civil war of that household. (15)

The attentive intellect which ‘counts the birds’ has as yet no language to describe or express his experience of the natural world, his ‘nameless weeds’. Still, he is possessive of it, seeing it as distinct from the human society which he can describe, yet does not identify with.

The ‘small farm’ referred to here belonged to his grandmother, Bridget Halpin, and like many other small holdings in Camas, it consisted of a meagre ten acres, three roods and thirteen perches. This woman, Bridget Halpin, would later wield great influence over her young grandson, Michael Hartnett. Indeed, if we are to believe the poet, she was the one who first affirmed his poetic gift when one day he ran into her kitchen in Camas and told her that a nest of young wrens had alighted on his head. Her reply to him was, ‘Aha, you’re going to be a poet!’. (A more detailed genealogy of the Halpin family and the early formative influences on Michael Hartnett can be read here).

Hartnett claimed that he spent much of his early childhood in Bridget Halpin’s cottage in the rural townland of Camas, five miles from his home in nearby Newcastle West. He went on to immortalise this woman in many of his poems, but especially in his beautiful poem, ‘Death of an Irishwoman’. This quiet townland of Camas must therefore be seen as central to his development as a poet, and maybe in time, this early association with Camas will be given its rightful importance, and the little rural townland will vie with Maiden Street or Inchicore as one of Hartnett’s important formative places.

‘Camas Road’, Michael Hartnett’s first ever published work, appeared in the Limerick Weekly Echo on the 18th of June 1955. He was thirteen. The poem describes the rural vista of the West Limerick townland of Camas at evening: ‘A bridge, a stream, a long low hedge, / A cottage thatched with golden straw’ (A Book of Strays 67). Its two eight-line stanzas of alternating rhyme and regular metre contain a litany of natural images, at times idiosyncratically rendered; the ‘timid hare sits in the ditch’, ‘the soft lush hay that grows in fields’. It is a peculiar mix of a poem, apparent images from both the poet’s lived and literary experience, placed side by side. It is contentedly denotative, creating a sense of ease and oneness with the natural world. The movement of sunrise to sunset is perpetually peaceful, its colours oils for the young poet’s palette. The ruminative introspection which elevates Kavanagh’s ‘Inniskeen Road: July Evening’, a poem which can be read in useful parallel to ‘Camas Road’, is not present. At the poem’s turn, as ‘Dark shadows fall o’er land so still’, Hartnett’s only thought and action are of flattened description, the creation of ‘this ode’.

‘Camas Road’ then, though essentially a curiosity which stands outside of Hartnett’s body of work, can be read as a seldom afforded snapshot of Michael Hartnett the poet before he became one. In contrast, his poem ‘A Small Farm’ shows a marked development in his poetic craft. Bridget Halpin, his grandmother, lived there with her son, Denis (Dinny Halpin), in what Hartnett describes as a prolonged state of ‘civil war’,

I was abandoned to their tragedies,

Minor but unhealing.

The word ‘abandoned’ here has many undertones and is important for the poet because he repeats the line twice in the poem. He has told us elsewhere that he was, in effect, ‘fostered out’ by his parents in Maiden Street, Newcastle West, to his grandmother, Bridget Halpin, from a young age and spent much of his childhood in her cottage in Camas. However, there is also the suggestion that while there he was ‘abandoned’ and somewhat neglected as he became an outsider, an unwilling observer of the ‘civil war’ of the household, as Bridget and her son Dinny constantly argued and fought over the minutiae of running a small farm in difficult times in the Ireland of the late 40s and early 50s.

Hartnett saw in his grandmother a remnant of a generation in crisis, still struggling with the precepts of Christianity and still familiar with the ancient beliefs and piseógs of the countryside. For Hartnett, there is also the added heartache that sees his grandmother struggling to come to terms with a lost language that has been cruelly taken from her. This, therefore, is a totally different place when compared to, for example, Kavanagh’s Inniskeen or Heaney’s Mossbawn or Montague’s Garvahey. However, there is an underlying paganism here that is absent from their work, although Montague comes close in his great poem, ‘Like Dolmens Round my Childhood, the Old People’.

For Hartnett, his grandmother represents a generation that lived a life dominated by myth, half-truth, some learning, and limited knowledge of the laws of physics, and therefore, as he points out in ‘Mrs Halpin and the Lightning’,

Her fear was not the simple fear of one

who does not know the source of thunder:

these were the ancient Irish gods

she had deserted for the sake of Christ.

However, Hartnett’s powers of observation and intuition were honed in Camas on Bridget Halpin’s small farm during his frequent visits. He tells us that he learnt much on that small farm during those lean years in the forties and early fifties,

All the perversions of the soul

I learnt on a small farm,

how to do the neighbours harm

by magic, how to hate.

The struggle to make a success and eke out a living was a constant struggle and burden. The begrudgery of neighbours, the ‘bitterness over boggy land’, and the ‘casual stealing of crops’ went side by side with ‘venomous card games’, ‘a little music’ and ‘a little peace in decrepit stables’. The similarities with Kavanagh’s ‘The Great Hunger’ are everywhere, but Hartnett does not name this place; it is an Everyplace. The poem is simply titled, ‘A Small Farm’, so there is no Inniskeen, Drummeril, or Black Shanco here. Still, the harshness and brutality of existence, ‘the cracked calendars / of their lives’ in the 50s in Ireland, is given a universality even more disturbing than the picture we receive from Kavanagh. Yet, it is here in Camas that he first becomes aware of his calling as a poet and, like Kavanagh, it was here that ‘The first gay flight of my lyric / Got caught in a peasant’s prayer’. And so, to avoid the normal household squabbles of his grandmother and her son, he ‘abandons’ them, turns his back on them, and begins to notice the birds and the weeds and the grasses.

The depiction of another agricultural custom is shown in ‘Pigkilling’. The joyful detailing of the killing of a pig at his grandmother’s farm in Camas eschews any characterisation of Hartnett as a simplistically environmental poet, denouncing all human domination over nature. Rather, it depicts the killing as a vital part of the rural community’s relationship with animal-kind, comparable to ritual.

Like a knife cutting a knife

his last plea for life

echoes joyfully in Camas.

This is one of the few Camas Poems that names the place and the central figure of the poem himself uses the pig’s bladder as a plaything: ‘I kicked his golden bladder / in the air’ (Collected Poems 125). Agriculture here is not mechanised but depicted as an ongoing, sustainable facet of rural life: the poem echoes the loss of many of these old rituals and crafts of the past, as Heaney does in his collection, Death of a Naturalist.

The townland of Camas is also central to an episode that the poet recounts for us in his seminal poem, ‘A Farewell to English’ (Collected Poems 141). This encounter hovers somewhere between reality and dream, aisling (the Irish word for a vision) or epiphany. The incident takes place at Doody’s Cross as the poet walks out on a summer Sunday evening from Newcastle West to the cottage in Camas. He is on his way to meet up with his uncle, Dinny Halpin. He sits down ‘on a gentle bench of grass’ to rest his weary feet after his exertions, when he sees approaching him three spectral figures from the Bardic Gaelic past – Andrias Mac Craith, Aodhagán Ó Rathaille, and Daíbhí Ó Bruadair. These ‘old men’ walked on ‘the summer road’ with

sugán belts and long black coats

with big ashplants and half-sacks

of rags and bacon on their backs.

They pose as a rather pathetic group, ‘hungry, snot-nosed, half-drunk’ and they give him a withering glance before they take their separate ways to Croom, Meentogues and Cahirmoyle, the locations of their patronage, ‘a thousand years of history / in their pockets’. Here, Hartnett is situating himself as their direct descendant and the inheritor of their craft, and the enormity of this epiphany occurs at Doody’s Cross in Camas: the enormity of the task that lies ahead also terrifies and haunts him.

Earlier in ‘For My Grandmother, Bridget Halpin’ (Collected Poems 52), he again alludes to the wildness, the paganism, the piseógs that surrounded him during his childhood in Camas. His grandmother’s worldview is almost feral. She looks to the landscape and the birds for information about the weather or impending events,

A bird’s hover,

seabird, blackbird, or bird of prey,

was rain, or death, or lost cattle.

This poorly educated woman reads the landscape and the skies as one would read a book,

The day’s warning, like red plovers

so etched and small the clouded sky,

was book to you, and true bible.

And yet, in his beautiful poem, ‘Bread’ (Collected Poems 53), he evokes and echoes the warmth and nurture of Mary Heaney’s kitchen in Mossbawn. His grandmother’s kitchen in Camas was a comforting place for him, and his early childhood memories are ones of coming home to roost,

and I come here

on tiring wings.

Odours of bread….

The picture we get of the small farm in Camas is rather etched out in generalisation and aphorism, and through the accordant clichés of petty hatred and ignorance, ‘how to do the neighbours harm / by magic, how to hate’, before Hartnett brings the glass into focus, employing idiosyncratic detail which establishes the world of the poem itself. As already mentioned, the cottage on this small farm was a Rambling House, a house where neighbours gathered to tell stories, play music and card games,

venomous card games

across swearing tables

His early poetry, then, creates a delicate balance between description and abstraction, the actual and the figurative. In this way, Hartnett’s particular subjectivity, his way of seeing, is established. In time, it would become his poetic currency. We are invited into the quintessentially old traditional Irish kitchen with its pictures of the Pope, the Sacred Heart, the statue of Our Lady, the Crucifix,

Here were rosary beads,

a bleeding face,

the glinting doors that did encase their cutler needs,

their plates, their knives, the cracked calendars of their lives

In this poem, therefore, Hartnett is following on from Kavanagh in shining a light into the domestic and interior life of rural dwellers not previously considered worthy of attention.

I have to mention one other poem, a quintessential Camas poem, which appears in the collection A Necklace of Wrens, published in 1987 after his return to Dublin. This is a collection of selected poems in Irish with English translations by Hartnett. The poem in question is titled ‘The Country Chapel’, with its Irish translation ‘An Séipéal faoin Tuath’. This memory poem describes the scene outside the country church on any given Sunday. The young, observant Hartnett describes the various characters who have come from the ‘fat meadows’ as ‘sly and happy’. They resemble ‘a set-dance team / by the wall of the old chapel’. They are all strategically placed depending on the various local rows and even their differing sporting and political allegiances, ‘foe avoiding enemy’. This eclectic group of neighbours are beautifully portrayed in the lovely Hartnett metaphor: ‘The congregation is a lonely horse’ who appear to be ‘as awkward as a man /dancing with a nun / on a wedding day’. This may well be a long-lost poetic portrait of the people of Killeedy, Ratheenagh, Ballagh and Kantoher in the mid-40s and 50s.

Bridget Halpin’s ‘small farm’ in Camas may have been small and full of rushes and wild iris, but it helped produce one of Ireland’s leading poets of any century. The influences absorbed in this rural setting, his powers of observation, his knowledge of wildlife and flowers, and his ecocentric bias, are impressive and are all-pervasive in these Camas Poems and, indeed, his poetry in general. Hartnett, the quintessential nature poet, would be delighted and impressed to see the magnificent new Killeedy Eco Park, which has been set up less than a mile from his ‘foster’ home in Camas by the combined efforts of that same local community in Killeedy. It is also significant that the visionary developers of this project have included a Poet’s Corner where Hartnett is remembered, just a stone’s throw from the small farm of his formative years. Here today’s generation in Camas and beyond can now come to ‘count the birds’ and the ‘nameless weeds’.

References

Hartnett, M. Collected Poems, edited by Peter Fallon, Gallery Press, 2001 (Reprinted 2012)

Hartnett, M. A Necklace of Wrens: Poems in Irish and English, The Gallery Press, 1987 (Reprinted 2015).

HARTNETT, M. A Book of Strays, edited by Peter Fallon, The Gallery Press, 2002, (Reprinted 2015).

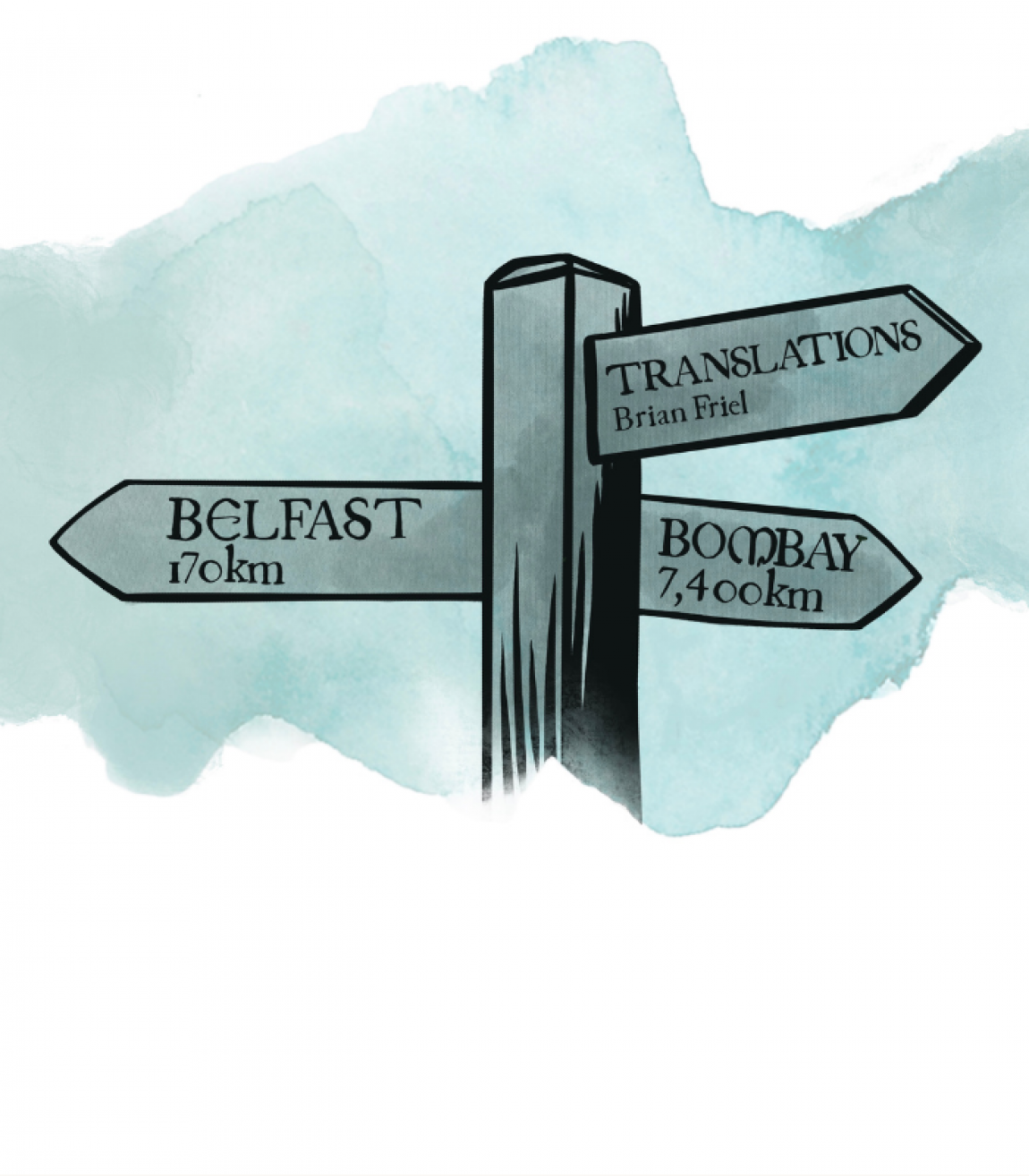

Translations is a three-act play by Irish playwright Brian Friel, written in 1980. It is set in Baile Beag (Ballybeg), in County Donegal which is probably loosely based on his beloved village of Glenties in West Donegal where Friel was a frequent visitor and where he is buried. It is the fictional village, created by Friel as a setting for several of his plays, including Dancing at Lughnasa, although there are many real places called Ballybeg throughout Ireland. Towns like Stradbally and Littleton were other variations and ‘translations’ of the very common original ‘Baile Beag’. In effect, in Friel’s plays, Ballybeg is Everytown.

Translations is a three-act play by Irish playwright Brian Friel, written in 1980. It is set in Baile Beag (Ballybeg), in County Donegal which is probably loosely based on his beloved village of Glenties in West Donegal where Friel was a frequent visitor and where he is buried. It is the fictional village, created by Friel as a setting for several of his plays, including Dancing at Lughnasa, although there are many real places called Ballybeg throughout Ireland. Towns like Stradbally and Littleton were other variations and ‘translations’ of the very common original ‘Baile Beag’. In effect, in Friel’s plays, Ballybeg is Everytown.

You must be logged in to post a comment.