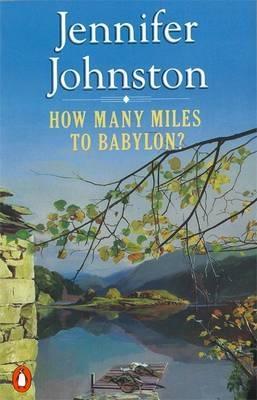

THE HISTORICAL AND LITERARY BACKGROUND

This novella was published in 1974 and is set at the time of the First World War. It depicts the culture of the Big House before its collapse as a result of the war and the 1916 Rising. The occupants of the Big House are sheltered from the reality of the world outside. They continue to live an ordered and leisurely life, which is only occasionally interrupted by distasteful reports of war injuries. As more and more local men enlist in the forces and many are killed or maimed, the war slowly becomes a reality for the family. When Alec enlists, this brings the war right into their home, and they are forced to acknowledge its existence.

Before he joined the British forces, Jerry had been involved in Republican activities in the local area, and this was his main reason for joining. He planned to bring back knowledge of fighting methods to use to good effect in fighting for a free Ireland. The location of the novel changes. It is now set in France in the heat of battle. Even though the hail of gunfire and the agonised screams of the wounded are always present, the novel focuses primarily on human emotions and man’s capacity to endure war.

THE STORY

This is a novel about friendship based on a young man’s experience in the First World War. Alec Moore is an only child from an Anglo-Irish family in Wicklow. There is a tense atmosphere in the home because Alec’s parents are estranged from each other. The boy from the Big House befriends Jerry Crowe, a local boy from a working-class background, and a close friendship develops between them.

As they grow older and the war intensifies, both men enlist in the British Forces for very different reasons and are sent to fight in France. Their friendship continues under the disapproving eye of Major Glendinning who forbids his officers to associate with junior soldiers.

Jerry deserts the army temporarily to search for his father who had gone missing on the battlefield. On his return, he is sentenced to death as an example to other soldiers who may be considering desertion. Alec, as an officer, is ordered to instruct the firing squad or face the same fate himself for refusing to obey orders.

The men exchange farewells and to avoid prolonging the agony, Alec kills Jerry in his room. He is sentenced to death for defying authority and the novel ends with Alec writing while calmly awaiting death.

THEMES AND ISSUES

1. Love versus Hatred

2. Friendship (Relationships)

3. War

Love versus Hatred In the novel How Many Miles to Babylon? Jennifer Johnston explores the theme of love versus hatred in an interesting way. Alec Moore must experience a horrific test of love in the course of the novel. He narrates his tragic tale of a loveless childhood, which left him emotionally scarred. His mother is cruel, manipulative and full of hatred for her husband whom she regards as weak.

From childhood, Alec was goaded by his beautiful mother, who is portrayed as being without nurturing or loving instincts. Mrs Moore’s physical beauty is contrasted with her vindictive personality. Her actions, which are swift and dismissive, suggest her passionless nature. Despite keeping a beautiful house hers is not a home where real love and affection are displayed: ‘The dining-room in the daytime was unwelcoming. It faced north and that cold light lay on the walls and furniture without kindness’.

Alec’s closest experience of love for his mother is related very early in the novel when he describes her daily ritual of strolling down the gravelled path towards the lake to feed the swans: ‘I heard her call once to them in a voice so unlike her own recognisable voice that for a moment I felt a glow of love for her’. This rather ironic revelation indicates her unloving attitude towards her son. It appears as though she loves the perfection of the swans, their separateness from her and their uncomplicated, instinctive existence.

For her, human relationships are meaningless unless she can gain some kind of power or victory from such intimacy. She uses her allure, the pretence of love, to secure what she desires while underneath she seethes with rage. He concludes that he ‘thinks’ his mother loved him but not in a way that he could understand.

Alicia Moore also disregards her husband’s feelings by constantly insulting him even in front of Alec; ‘I have no intention of remaining alone in this house with you. I have already said that. Made myself quite clear, I thought’. When she discovers the friendship between Alec and Jerry Crowe she moves swiftly to destroy it. Not only is she averse to the mixing of the classes but she is also suspicious and aggrieved at the bond which exists between the boys. Her refusal to allow Alec to go away to school is not the result of her grief at their separation but because she would be left alone with a husband she detests. She uses her son in a most despicable way, as a buffer between herself and her husband. She brings her son to Europe not for the love of learning but as a means of dealing with his unsuitable friendship with Jerry.

Friendship Alec feels real affection for his father. He realises that his mother abuses his father but he is helpless to prevent it. It has to be acknowledged that Alec’s father is partly responsible for the maltreatment he receives. He misjudges Alicia, only realising his mistake when it is too late to rectify it. It is interesting to note that Mr Moore deteriorates in the absence of his son. When Alec returns after four months in Europe, he notices a change in his father, ‘My father had failed a little during our absence … but he seemed a smaller man than I had remembered’. It is also interesting to note the way that Frederick’s defective eyesight is highlighted in the novel – we deduce from this that he lacks the insight necessary to recognise true love and he suffers grievously for this defect.

The friendship which develops between Alec and Jerry is the only real love and affection which Alec experiences. Jerry makes Alec’s dreary life more bearable with his sense of fun, adventure and good humour. He mimics and makes fun of Alec’s education and he ‘sends up’ the Anglo-Irish ‘set’. However, he shares the same sad home life as Alec. His father is distant and his mother is unloving and apparently greedy for money: ‘She wants me to join the army … follow me, dad. Then she’d have two envelopes arriving. On the pig’s bloody back.’.

The boys’ friendship is firmly fixed not only because of their sad home lives but also because of their passion for horses and nature. Both Alec and Jerry are capable horsemen. They plan to somehow overcome their class barriers to breed and train horses together.

War The images of hatred in the novel revolve around references to the First World War and the Irish Nationalist cause. From the earliest moments in the novel, the impending war in Europe forms the backdrop to the feuding husband and wife. It is possible to argue that the hatred between Alicia and Frederick Moore is used as a compressed image of the hatred between the allied and enemy forces in the war.

The inferences to madness in the novel serve the same moral function as the images of war. They make the reader understand that love is the essential element to the survival of the world because without it there is only chaos, cruelty and hatred. Alec’s decision to go to war is partly a consequence of his mother’s hateful behaviour, but the insanity of the war, the death and maiming, proves that it too is a destructive human force.

Alec’s relationship with his father is affected by the war. Alec’s decision to become a soldier leaves his father bereft of his only source of love. Their parting scene in the novel, though it seems superficial, is actually heart-rending. Given the period in which the novel is set and the class to which they belong, Alec and his father do not show the intensity of their feelings for each other but it is evident in Frederick’s actions and his son’s private reflections. Alec accepts the money which his father gives him, understanding it as a gesture of love: ‘Don’t let yourself go short. Anything you want’. Similarly, the gold watch which the father gives the son is used metaphorically, as though it represents his beating heart, that somehow if Alec kept his watch close to him it would protect him from danger, give him comfort by reminding him of his father: ‘It was warm in my hand with the warmth of his body. I put it into my pocket with the money’.

Alec’s mother sees his decision to become a soldier as a personal triumph. Having goaded him earlier about his cowardice, she can now ‘enjoy’ and ‘suffer’ the sympathy of her peers about giving a son to the war effort. Both Jerry and Alec ridicule their mothers for their hypocritical show of grief as they go to war. Jerry’s reference to ‘candles and novenas’ and ‘bending the ear of God with decades of the rosary’, illustrate his sense of alienation from his mother. Alec satirises Alicia for her insensitivity towards him: ‘Mine played Chopin triumphantly on the piano the moment I left the room’.

The description of the war in the novel evokes a sense of horror in the reader. The trenches which Alec describes are a physical representation for the reader of humankind without the redemptive power of love. It is like descending into the hell which he describes so well in the course of the novel.

We can plot the gradual degeneration of Alec’s physical condition over the course of the war. However, Alec’s love for his friend remains intact despite the class barriers between ranks in the army. Alec embraces the friendship of Jerry, caring for his welfare and trying to buffer some of the abuse hurled at him by the officers.

When Major Glendinning reprimands Alec for his friendship with Jerry, arguing that ‘strict impersonal discipline’ must be maintained between the men, he is actually arguing that there is no place for sentiment (or love) in the army. It seems that Alec and Jerry should become insensitive to feeling and the little kindnesses which make life bearable. Yet despite this ultimatum, Alec continues to befriend Jerry and their smallest gestures of help to each other indicate the pointlessness of the war which rages around them.

The murder of the ‘Gloucester’s regiment’ soldier by Glendinning is carried out with precision and dispassion. This murder illustrates the breakdown of the inherent moral code in humanity. After the murder, Glendinning never once shows remorse or disgust for his act. His dispassionate nature is illustrated again when Alec requests leave for Jerry to find his father, who was reported missing in action: ‘The answer is no. Crowe goes to the front again tomorrow with the rest of his squalid friends.’

Jerry also abides by his sense of filial duty and wants to find his father, ‘if he’s wounded maybe there’d be something I could do for him’. Jerry’s compassion for his father is contrasted with a very good description of the barbarity at the front.

Friendship The reunion between Jerry and Alec near the end of the novel is very moving. This poignancy is more effective because the reader of the novel suspects that the reunion will be short-lived:

He threw an arm across my shoulders and we lay in silence. My warmth was spreading through him, but the hand that clasped the back of my neck was still cold as a stone fresh from the sea.

When Jerry is found he is put into the detention camp where Alec visits him to carry out the greatest test to their friendship and love. They reminisce about their youthful dreams and ambitions. Jerry confesses for the last time that he loves his country above his king. It seems an odd thing to say before death but it is important to remember its symbolic significance. For Jerry, his country encompasses more than the nationalist cause, more than the land itself; it reflects his belief about the brutality of war, the uselessness of it. When Alec pulls the trigger he has committed no gross act of murder but has saved his friend from a shameful death by firing squad: ‘They will never understand. So I say nothing’.

Without Jerry, there is no love in Alec’s life and he becomes indifferent to everything and everyone and he effectively withdraws from life after Jerry’s death.

LITERARY GENRE

This novel fits into the category of social realism. It is a story which is extremely true to life. Johnston does not over-exaggerate her plot or stretch it beyond the bounds of credibility. It is a novel based firmly in an actual time and place in history. Her main characters belong to clearly defined social backgrounds, the Anglo Irish gentry and the Catholic underclass of Ireland in the early 1900s. Both men are accurately drawn as they each possess certain qualities of their respective backgrounds. The bigotries which attempt to divide them both at home and on the battlefield are all too real in the novel.

All of the events are quite plausible, such as when the men escape briefly on horseback to have a good time and avoid the reality of the trenches, or when the Major ends a man’s suffering because it may have a negative effect on his men. Also, Jerry’s escape to search for his father is believable and his death sentence fits in all too well with the personality of Major Glendinning. It is, therefore, a book rooted in reality.

THE STRUCTURE OF THE NOVEL

This novel is written in the form of a first-person narrative. At all times the reader shares Alec’s view on life and his interpretation of the things which occur to him or around him. In many respects, the novel takes on the form of an autobiography. It could also be said to be a confessional work. It begins with an officer alone in his room, about to face death by firing squad and he is writing his last thoughts. Therefore, the novel is told in flashback.

He begins by reflecting on his life, ‘As a child I was alone’, and the story develops as the officer goes back over his past as a child, his life as a man in the trenches and the events which led up to his imminent death. The novel is presented strictly in chronological order with only a few slight references to the past, as Jerry and Alec at times of depression or crisis look back longingly to the good times they spent together in the Irish countryside. It is divided into two distinct settings: Ireland and France. It ends with Alec in captivity beginning to write his last words, so that the novel has come full circle and ends as it began, ‘So I sit and wait and write’. It is a simply structured but completely effective novel with a plot that is uncomplicated and direct.

THE STYLE OF THE NOVEL

Jennifer Johnston’s use of language is striking. She does not waste words on rambling descriptions nor does she overuse images for exaggerated effect. This makes her images all the more memorable when she does use them. Clarity is her main strength. She describes her characters and the action in the plot in a concise condensed manner.

Many of her descriptions are based in nature:

‘Memories slide up to the surface of the mud, like weeds to the surface of the sea, once you begin to stir the depths where every word, every gesture, every sigh, lies hidden.’

‘Rain was in the air. The rushes bowed to her as a little rippling wind stirred through them. A thousand green pikemen bowing.’

‘The swans would allow themselves to drift on the wind like huge crumpled pieces of paper hurled up into the sky.’

She also conveys the desolation of the Irish landscape very well:

‘The lake was in one of its black moods. It heaved uncomfortably and its blackness was broken from time to time by tiny figures of white, mistakes.’

The loneliness of the characters who inhabited that desolate landscape and the emptiness of the family atmosphere is also beautifully expressed:

‘Their words rolled past me up and down the polished length of the table. Their conversations were always the same, like some terrible game, except that unlike normal games, the winner was always the same. They never raised their voices, the words dropped malevolent and cool from their well-bred mouths.’

The emptiness of the Irish landscape and the emptiness of the inhabitants of the Big House are matched by the desolation of the war fields. The desolate landscape of Flanders is reflected in the ‘leaden rain which fell continuously’ or ‘The wind was blowing straight in our faces and the drops were like a million needles puncturing our skin.’

Johnston introduces a vivid comparison when she introduces war for the first time. As the men trained on the shores of Belfast Lough, ‘It was like some mad children’s game, except that the rules had to be taken seriously.’ The mental torture which the men were subjected to was brought out in the description of the man screaming:

‘Out beyond the wire, a man was screaming. Not a prolonged scream, it rose and fell, faded, deteriorated into a babbling from time to time and then occasionally there was silence. During the silence you could never forget the scream, only wait for it to start again. The men hated the sound as much as I. You could see the hate on their faces.’

Johnston also uses symbols to good effect in the novel. At intervals in the book, the swan is used as a symbol of loyalty and eternal friendship. Alec and Jerry share a common love and respect for swans as they begin to know each other. Swans reappear in Flanders, both literally and metaphorically. At times of crisis as the men struggle to endure the hardship of the war, they remember the swans in the few rare glimpses the reader gets of the past. At the end of the novel, as Alec leads his men to a new location, two swans fly overhead and a man kills one for fun, to Alec’s horror. This symbolises the imminent death of Jerry as the bond of friendship between him and Alec is about to be severed.

Another literary device favoured by Johnston is the use of rhyme and poetry at crucial moments. The title of the novel is taken from a well-known children’s rhyme:

How many miles to Babylon?

Four score and ten, sir

Will I get there by candlelight?

Yes and back again sir.

This was a rhyme that Alec learned innocently as a child and it comes back to haunt him as an adult. It is referred to three times in the early part of the book and again just as Alec leaves for the war: ‘Will I get there by candlelight?’ This reflects Alec’s uncertainty as he heads off into the unknown, to some ‘Babylonic’ place, unsure if he will ever return again.

Lines of poetry are sprinkled through the novel when Alec is at his most philosophical: ‘I was being troubled by the poetry of Mr Yeats’. As children, Alec introduces Jerry to Yeats on the shore of the lake:

Rose of all roses, Rose of all the world

And heard ring

The bell that calls us on; the sweet far thing.

In contrast to this, Yeats reappears in a very different situation. A line of Yeats’ slips out involuntarily as Alec sees a man writhing in agony on the battlefield:

Far off and secret and inviolate Rose

Here he is experiencing his strongest emotional test and it is significant that he turns to Yeats for help. There are echoes of Yeats’ work in many places in the novel, for example, Alec’s statement at the very beginning of the novel: ‘I am committed to no cause. I love no living person.’ This reminiscent of Yeats’ poem ‘An Irish Airman Foresees his Death’. Jerry also compares Alec’s mother to Helen of Troy, a striking beauty often admired and featured by Yeats in his work.

While Alec quotes the poetry of Yeats, Jerry uses a different kind of rhyme to show his dedication to the Republican cause:

Now father bless me and let me go

To die if God has ordered so.

This emphasises some of the differences between the two men.

Humour is sparse in the novel and when used it is often grim. It is evident on the morning when Alec leaves for the war and it is used by the soldiers at moments of stress to lighten their moods.

Dialogue is used sparingly and it is often loaded with inferences particularly in the relationship between Alec and his parents. The absence of words only illustrates the lack of communication within the family. Dialogue is not favoured by Major Glendinning who uses short, sharp sentences. These have the primary function of giving orders and he forbids discussion as much as possible.

Johnston’s style of writing is compact yet lucid. It is extremely effective as it invites the reader to fill in the gaps and particularly to infer meaning from the electric silences which permeate the story.

CULTURAL CONTEXT

While Alec and Jerry have lived in close proximity to each other in Ireland there is a strong contrast between their backgrounds. Alec is the only child of an aristocratic couple whose values and beliefs differ significantly from those of the Catholic people of the time. The socials division between both groups was strong yet Alec and Jerry chose to ignore it. Alec’s mother forbade him to see Jerry and his father, for once, agreed with her that it was an unsatisfactory relationship:

‘It is a sad fact, boy, that one has to accept young. Yes, young. The responsibilities and limitations of the class into which you are born. They have to be accepted. But then look at all the advantages. Once you accept the advantages, then the rest follows. Chaos can set in so easily.’

Both boys were also educated differently. Alec had the doubtful pleasure of his own tutor, Mr Bingham, and a piano teacher. This meant that Alec never mixed with other boys of his own age as a child and therefore his friendship with Jerry was particularly important for him. Jerry, on the other hand, went to an ordinary school but had to leave early to find work. Alec naively suggested that Jerry could work in his father’s stables, but Jerry knew that this would end their friendship. Their respective cultural backgrounds would raise innumerable barriers between them: ‘Why is neither here not there. Your lot would care. My lot too if it came to it. One’s as bad as the other.’ Alec realises the truth of Jerry’s statement:

Yes, I knew they would care. He was right. My mother would purse up with disapproval, her voice rise alarmingly as it sometimes did when she spoke to my father.

Both men enlisted in the army for different reasons. Alec did so to escape from a disintegrating family structure, driven by the knowledge that he was not his father’s son. This was a damaging experience for him and now that the blood ties had been broken and he was dispossessed both emotionally and financially, he saw little hope for a positive future. He felt a strong desire to get away from his parents and war offered him an opportunity. Alec cut himself off and drifted into war in the hope of blocking out thoughts of reality.

Jerry had been involved in Republican activities and this was his main reason for joining. He planned to use his knowledge of fighting to fight for a free Ireland on his return. He tells Alec on the night before they leave that he also needs the money: ‘Or maybe the thought of all those shiny buttons appeals to me’. Whatever his reasons, Jerry cares little for the cause he will be fighting for, as his own personal needs are a priority.

On the battlefield itself, the cultural background of the soldiers is unimportant when men are facing a life and death crisis, yet ironically the distinction between gentry and peasantry is maintained by the emphasis on army rank. It is a strange paradox: background is irrelevant yet is of ultimate importance. Men cling to the importance of rank as it gives them a feeling of stability when everything else is crumbling around them. Alec and Jerry disregard this as the war intensifies.

Culturally, while there are many differences between them, Alec and Jerry are alike in that neither of them is attempting to be a hero who will come back decked with glory, as Alec’s mother would certainly like him to be. Neither of them is driven by a strong desire to win the war for the people. Both of them are using the war as an opportunity to resolve or escape painful issues in their own lives.

Another cultural contrast made by Johnston is to highlight the differences between the Irish and English soldiers. There was a certain amount of lighthearted banter between Alec, Jerry and Bennet when they were out on horses:

‘Don’t be such a damned English snob’ or ‘Irish sentiment creeping in. Perspective is needed. You damned Celts have none. It’s no wonder we don’t think you’re fit to rule yourselves.’

Major Glendinning also had difficulty with the fact that he had Irish soldiers to deal with and in a moment of anger declared to Alec: ‘I never asked for a bunch of damn bog Irish’.

Concluding Comments

How Many Miles to Babylon? is not a novel solely about war. Although World War I is in the background, Johnston also touches upon Irish history, in particular the tensions between the Irish and the British. Through Jerry’s revolutionary leanings and the harsh comments about the Irish made by Major Glendinning, Johnston hints at the coming battle for Irish independence.

Alec, the narrator, is a very passive character for most of the book. Just like his father, he submits to his mother’s every demand. When she told him that he has to go to war, he protests that he has no desire to fight or be killed, but he ends up doing what she expects of him anyway. In many ways the novel is a tragedy of obedience: Alec, the isolated only-child in an Anglo-Irish big house, is a pawn in his parent’s pathological relationship. “Oh, you’ll go, my boy,” his fatalist father tells him. “You’re a coward, so you’ll go.” In contrast, Jerry is more of a free spirit, making his own decision to go to war and speaking out when he should keep his mouth shut. With Alec as narrator, the book moves a bit slowly, possibly because I didn’t have any strong feelings for him until the very end. Still, there’s a beauty to Johnston’s prose that kept me glued to the page.

How Many Miles to Babylon? is one of those novels that hit you hard at the end. The ending says so much about the characters, and it was both a satisfying end to the journey and one that left me wanting to know what happened next. Johnston surprised me and I’ll certainly be thinking about this book for a while. Amazingly, there are only two deaths described in the novella, yet, for me, it remains a stark depiction of devastation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.