AMONGST WOMEN

John McGahern

About John McGahern (1934 – 2006)

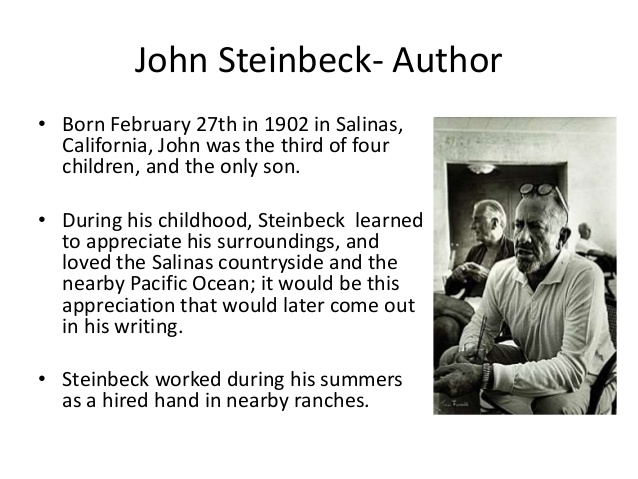

One of Ireland’s most widely read authors John McGahern was born on November 12th, 1934. The family lived in Leitrim until his mother’s death in 1945, when they moved to their father’s home at the police barracks in Cootehall, County Roscommon. In his early twenties McGahern worked as a teacher and wrote an unpublished novel, The End and the Beginning of Love. His first published novel, The Barracks (1963), won the AE Memorial Award and earned him an Arts Council Macauley Fellowship. His next novel, The Dark (1965), was widely praised and drew comparisons to James Joyce, but it also offended the Archbishop of Dublin and the state censor, who banned the book and he was also sacked from his teaching position.

He refused, however, to capitalise on this notoriety, instead continuing to publish quietly. Three novels followed – The Leavetaking (1974), The Pornographer (1979), and Amongst Women (1990; winner of the Irish Times Award and short-listed for the Booker Prize). McGahern’s four volumes of short stories were published in The Collected Stories in 1992.

His final novel That They May Face the Rising Sun (published in the United States as By the Lake) is an elegiac portrait of a year in the life of a rural lakeside community. McGahern himself lived on a lakeshore and drew on his own experiences whilst writing the book. Lyrically written, it explores the meaning in prosaic lives. He claimed that “the ordinary fascinates me” and “the ordinary is the most precious thing in life”. The main characters have – just like McGahern and his second wife, Madeline Green – returned from London to live on a farm. Most of the violence of the father-figure has disappeared now, and life in the country seems much more relaxed and prosperous than in The Dark or Amongst Women.

During his writing career, he served as a visiting professor at Colgate University and the University of Victoria, British Columbia, and he was writer-in-residence at Trinity College, Dublin in 1989. He died from cancer in the Mater Hospital in Dublin on 30 March 2006, aged 71. He is buried in St Patrick’s Church Aughawillan alongside his mother.

Historical and Literary Background

This novel is set in Ireland in the years following the Irish War of Independence. We hear references to reviving Monaghan Day, which is obviously a tradition of the time. The story is set in the country and outlines the position of the family of the time. It may be worth mentioning that Patrick Kavanagh’s The Great Hunger was written about rural life in Ireland about this time also. Are there any similarities between Moran and the character of Paddy Maguire?

During these years, post War of Independence and pre World War II, McGahern tells us family bonds were strong. The Moran family is united, in spite of their father’s erratic temperament. Luke is the only exception to this happy picture of family solidarity.

Women married securely in this society. Secure jobs such as the civil service were recommended. Study at the university was not financially possible for Sheila. The profession of doctor is also not acceptable within this family because the doctors had emerged as the bigwigs in the country that Moran had fought for during the war.

We also see the faithful practice of the rosary. This is a prayer that is said by the family every night. Moran makes use of this to assert his dominance over the family while refusing to face his own shortcomings.

One of Moran’s big fears is being poor. For this reason he is miserly with money and even though he eventually gets two pensions he still exerts a tight control over the finances. He also takes pride in the land he owns. He uses the land as a refuge, many times escaping from the house to work furiously at hay-making or reaping whenever he loses control of himself.

At the end, on his death, Moran is given the typical Republican burial with the tricolour draped over his coffin. (Check the front cover of the novel!)

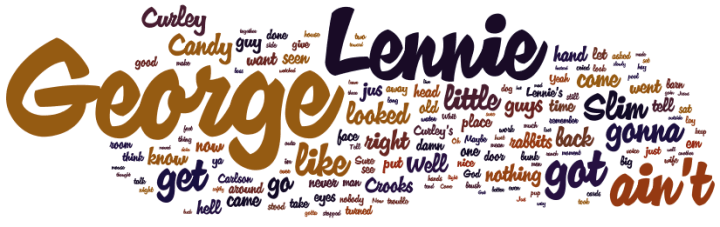

THE STORY

The story is based on the Moran family who live in Mohill, Co. Leitrim. The house is called Great Meadow. The story is told in flashback and is framed at beginning and end with Moran in a depressed state and wishing for death. Moran is an old Republican who was a guerrilla leader in the War of Independence. His wife is dead and he is left to bring up their five children; three girls and two boys. Luke is the oldest and he has gone to work in London because he will not tolerate his father’s violent behaviour. Moran can never forget the authority he wielded during the war and tries to behave in the same way within his household. He continually uses the rosary to regain control and power over his family. Moran marries a girl called Rose Brady when he is beginning to get old. Initially Rose is very idealistic about the marriage, but she soon discovers the true nature of Moran and his capacity for violence and dark moods.

Rose is a very selfless person who clearly loves Moran in spite of his strong character and difficult temperament. She encourages the girls to become independent and achieve the best they can in life. Maggie settles in London and eventually marries, as does Sheila. Mona gets a good job in the civil service and remains single. Michael, the youngest, leaves and marries. Luke’s refusal to return to Great Meadow, the family home, frustrates and angers Moran greatly. All the rest of the family visit him regularly in spite of the fact that he has been domineering and violent. They are all happy together and have learned to accept Moran’s peculiar temperament. Moran dies at the conclusion. Everyone except Luke turns up at his funeral and acclaim him as a truly great and heroic man

LITERARY GENRE

This is a novel of social realism, which is written in the third person omniscient narrative voice. It can, therefore, be classed as a social document that is set in Ireland in the period following the War of Independence. There are no official chapters; the narrative is broken into sections separated by a short space. Much of the story is told through dialogue, which gives a vivid insight into the various characters. The first section is written towards the conclusion of the story when Moran becomes sick. The rest of the story gives an extended account in flashback about the life of the Moran family in Great Meadow.

There is a great similarity between Amongst Women and William Shakespeare’s great tragedy, King Lear. By insisting that each of his daughters proclaim her love for him to win her share of his kingdom, Lear sets in motion a plot that reveals the complex dynamic at work among an elderly patriarch and his three daughters. Like King Lear, Amongst Women investigates the love between a father and his children, the struggle to maintain strength in advancing age, and the difficulty of negotiating between independence and an identity tied to family roots.

THEMES AND ISSUES

There are a number of themes and issues raised in the novel. The main themes dealt with here are:

- Power/Control/Patriarchy

- The Family

- The Role of Women

Power/Control/Patriarchy

Moran has been a guerrilla fighter in the War of Independence. He never got used to the failure of that war, and so he tries all his life to master his family and dominate them. It is only when he feels he is in control and the centre of things that he can manage to deal with issues in life. Much of his power is achieved through violence and physical abuse. He also uses the rosary as a weapon to establish his control in the house. When he marries Rose Brady things change slowly but subtly. He verbally abuses her several times but her firm reaction chastens him and shows him the need for self-control. When there are difficulties with young Michael who begins to drink and womanise, Moran threatens to use physical violence to control him, as he had once done with Luke. Michael runs away to England and gets a job. Moran is left on his own with Rose and simply becomes more introverted and depressed. As an old man he loses the ability to exert control through his mood swings and violence. He changes and writes a letter of apology to his oldest son Luke who has left him a long time ago.

***

Amongst Women can be seen as a critique of patriarchy. McGahern connects nationalism, Catholicism and patriarchy in an unholy trinity. In the novel McGahern is turning away from the Big House novel, that had played such a big part in earlier Irish fiction, to what might be termed the small house novel, portraying rural Catholic family life. In the novel death frames the novel, but the intervening narrative is an extended flashback to family life in Great Meadow with Moran bestriding his little kingdom as a crusty, would-be Colossus. The relationship between him and his wife and children is the principal focus of this plotless novel. The focus is on scenes in which some or all of the family are assembled and the narrative moves in and out of the consciousness of various members of the group. In this novel, for the first time in his writing, the subject of patriarchy assumes a central theme.

‘Only women could live with Daddy,’ Moran’s alienated son, Luke, comments, and the novel, to some extent, endorses this viewpoint. Moran is first encountered ‘amongst women’, an ailing old man fussed over by his wife and three daughters. The theme of the relationship between power and gender is announced in the opening sentence. Moran’s physical weakness has transformed relations between him and his womenfolk to one of fear on his part and dominance on theirs. However, even at his most physically incapacitated, Moran has still not lost his hold over his daughters: he ‘was so implanted in their lives, that they had never left Great Meadow’ (p.1).

The narrative pulse of Amongst Women is one of homecoming and leave-taking: welcomes and farewells at the train station; cars turning in the open gate of Great Meadow under the poisonous yew; children leaving home to embark on their adult lives, all but one drawn back with increasing frequency as the years pass; happy family reunions and the sad final reunion at Moran’s funeral. Initially the rhythm is homecoming, and the verb ‘come’ is repeated seven times on the first page. The reader is being drawn into this world where Moran is at the centre. By the end of the second paragraph we have been introduced to its setting and principal characters: the ‘once powerful’ Moran, his second wife, Rose, his three daughters, Maggie, Mona, and Sheila, his younger son, Michael, and the eldest, Luke, distinguished from the rest by his refusal to come back to Great Meadow.

Patriarchy in Amongst Women can be seen to derive to a great extent from patriotism. Moran is the hero of the War of Independence, who has failed to make a successful career in the Irish army in peacetime, directs his frustrated drive for power into a diminished form of home rule. His status as a former guerrilla fighter is repeatedly emphasised at the outset by the device of juxtaposing two episodes which celebrate his youthful exploits as leader of a flying column, thereby ensuring that all his subsequent conduct is ‘placed’ in the light of this wartime experience. Monaghan Day, a fair day in late February when he received an annual visit from McQuaid, his former lieutenant, and the two reminisced over their youthful heroics, is Moran’s equivalent of Remembrance Day. The novel opens with his daughters’ revival of Monaghan Day when Moran is old and ill. On this occasion he deglamourises his role as freedom fighter and refers to his flying column as ‘a bunch of killers’ (p.5). That he has never lost his own killer instinct is demonstrated next morning when he rises from his sickbed to shoot a jackdaw. His targets may have diminished, but he is still prepared to resort to violence to assert his limited power. The incident rather pathetically demonstrates his present impotence, yet he himself uses it to illustrate his connection between intimacy and mastery:

The closest I ever got to any man was when I had him in the sights of my rifle and I never missed. (p.7)

Moran is at pains to tell his wife and daughters that his flying column did not shoot women or children, treating both categories as minors or inferiors.

Beginning on P. 8 we are given another flashback to the last Monaghan Day. In this episode Moran’s bullying of his teenage daughters is contrasted with his inability to gain power over McQuaid. He terrorises his daughters, so that in his presence they ‘sink into a beseeching drabness, cower as close to being invisible’ (p.8) as possible, but it is obvious now that his power does not extend outside his own family. McQuaid, who has long outstripped Moran in terms of worldly achievement, is happy to indulge in war memories for an evening, but he is unwilling to perpetuate his former role of junior officer. His visit brings something of the secular, commercial outlook of modern Ireland into the pious, traditional world of Great Meadow. Here again the rhythms of arrival and departure are evident as the annual ritual of Monaghan Day is brought to an end with McQuaid’s abrupt exit. Henceforth, the cars that turn ‘into the open gate under the yew tree’ will convey returning Morans. From here on Great Meadow becomes a house hospitable only to its own family.

As has been said already, Amongst Women offers a penetrating critique of patriarchy. McGahern goes even further and shows that patriarchy as a refuge of the socially ill-adjusted and emotionally immature man and asks probing questions about the cult of family. Moran has transformed his inadequacies into a show of strength by making his home his castle. Denied a role as founding father in the Irish state he sets up his own dominion. Actually, Great Meadow, bought with his redundancy pay from the army, should be a monument to Moran’s failure to live up to his youthful promise. Though it is not an ancestral home it becomes, under his regime, a family seat, more cut off from the life of the surrounding village than any Big House. Because of an inability to relate to his fellow-villagers, Moran turns his family into a closed community and the absence of any outside contacts further strengthens his own paternal supremacy. He successfully indoctrinates his children with the idea that such reclusiveness denotes exclusiveness, that to be ‘proud’ and ‘separate’ is a mark of distinction, to be friendly and extroverted a sign of commonness. House and family are connected in exhortations to his daughters: ‘Be careful never to do anything to let yourselves or the house down.’ (p. 82). He thus forges an association between family and farmstead, roots his children in a ‘perpetual place’. As the founder of a new dynasty Moran acts as if he were self-propagated and never refers to his own parents. His cult of family does not include any filial loyalties which might conflict with the prior claim of being a Moran of Great Meadow, so he actively discourages his wife’s visits to her family home.

Moran’s family is an extension, a ‘larger version’ of himself. When he promotes the values of home and family he is obliquely bolstering his own self-importance. The ‘good of the family’ provides him with a virtuous, unselfish motivation for suiting himself. When he is about to remarry, for instance, he tells his daughter Maggie that he is doing so in the best interests of the family, though it has just been revealed to the reader that his only motive is his own future welfare. He also repeatedly stresses that all his children are equal, further emphasising his own unique superiority. The ex-officer promotes esprit de corps, though his theatre of operations is a hayfield and not a battlefield: ‘Together we can do anything.’ Such affirmation of solidarity and de-emphasising of individual differences serve to bind the family into ‘something very close to a single presence.’

In view of the novel’s critique of patriarchy it is interesting to note the effect this has on his daughters at the end of the novel. Turning the page at the end of the novel, we are given a glimpse of what ‘becoming Daddy’ means. A reversal of gender roles takes place as brother and husbands, seen from a patriarchal perspective, are transformed into wives. It is obvious that Moran’s honorary male daughters have inherited his contempt for the feminine, which they associate with levity and amusement:

‘Will you look at the men. They’re more like a crowd of women,’ Sheila said, remarking on the slow frivolity of their pace. ‘The way Michael, the skit, is getting Sean and Mark to laugh you’d think they were coming from a dance’ (p. 184)

Their exclusiveness as Morans of Great Meadow is such that it does not even embrace their own husbands and children.

It is also worthwhile to consider here the links between Catholicism and patriarchy. These links are forged in the novel by its most repetitive narrative ritual and the family prayer from which it derives its title. Moran’s devotion to the rosary is explained on familial and patriarchal grounds. ‘The family that prays together stays together,’ he observes, quoting the Rosary-crusader priest, Father Peyton. As in many Irish homes, (in the past?) the rosary in the Moran household is a public prayer that reinforces a hierarchical social structure: it is presided over by the head of the family and the five decades are allocated from eldest to youngest in descending order of importance. Though the rosary repeatedly pronounces Mary as ‘Blessed … amongst women’, because she was chosen to be the mother of Christ, in the Moran household, the character, blessed amongst women, is Moran himself. He even manages to die ‘amongst women’, since his son Michael is temporarily absent! The Rosary is peculiarly identified with Moran and it is a very clever device used by McGahern to emphasise the narrative repetitiveness, which is a feature of this novel. Over and over again the newspapers are spread on the floor, Moran spills his beads from his little black purse, and all kneel in prayer. The stability conferred by ritual and repeated phraseology underscores the disruptions and changes that the passage of time brings to Great Meadow.

Yet we should not be over negative in our assessment of Moran and his little kingdom. He does exhibit some inherent attractive qualities. Indeed his portrait is the most imaginatively generous picture of a father in McGahern’s many novels and short stories. He radiates enormous energy and this surely can be seen as a redeeming feature. He also shows great anguish for the son who is lost to him and he also shows a certain bafflement and frustration in the face of oncoming death. In particular he is associated with the annual haymaking, an activity shared by the whole family. From distant London or Dublin, Great Meadow in summer appears a therapeutic, pastoral world: ‘The remembered light on the empty hayfields would grow magical, the green shade of the beeches would give out a delicious coolness as they tasted again the sardines between slices of bread: when they were away the house would become the summer light and shade above their whole lives’ (p.85). Such memories turn Moran’s children into true Romantics, sustained ‘amid the din of town and cities’ by images of their fatherland.

Therefore, McGahern manages to balance the attractive and the repellent aspects of patriarchy in this novel. The glorious revolution that brought about the Irish State is so remote by the time of Moran’s death that the fellow revolutionary who tends to the faded tricolour on the coffin seems as old as Fionn or Oisín. Nevertheless, the legacy of the War of Independence, seen by some as a triumphalist, masculine ethic of dominance, has been passed on to the next generation.

Irish people everywhere seem to have an often inexplicable affection for their country, whether they be urban, suburban, rural or living in Boston. This love for ‘the ould sod’ is turned on its head here in this novel in McGahern’s examination of home, farm and fatherland. Idyllic though Great Meadow often appears, access to it involves passing under ‘the poisonous yew.’

The Family

In Amongst Women we see the powerful bond of the family and how it can withstand so many difficulties. Even though Moran is stubborn and mercurial in temperament, the family remain strongly bound together. Together they feel invincible in the face of the outside world, and when they gather together at Great Meadow, each member feels bound by this strong family unit.

The novel pulls us into a tight family circle with its first sentence – ‘As he weakened, Moran became afraid of his daughters’ (p.1). A ‘once powerful man’ (p.1), Michael Moran was an officer in the Irish War of Independence in the 1920’s. He was intelligent, fierce and deadly, but like many soldiers after a war, he felt displaced, unwilling to continue in the military during peacetime and unable to make a good living in any other way. ‘The war was the best part of our lives,’ Moran asserts. ‘Things were never so simple and clear again’ (p.6). While the army provided the security of structure, rules, and clear lines of power, Moran’s life after the war has consisted of raising two sons and three daughters on a farm and scraping out a living with hard manual labour. A widower, Moran confuses his identity with the communal identity of his family in a gesture that divides and conquers. Moran’s daughters are ‘a completed world’ separate from ‘the tides of Dublin and London’ (p.2). As such, he can control them, as when he discourages one from accepting a university scholarship. No longer powerful, Moran is repeatedly described as withdrawing into himself ‘and that larger self of family’ (p.12) in order to channel his aggressions into a shrunken realm he attempts to control. He can be tender with his children, but he also berates and beats them. His adjustment from guerrilla fighter to father is never complete, and the question of how to maintain authority over children while allowing them room to grow is central to the novel.

Nowhere is this struggle between dependence and independence more pronounced than in the character of Luke, the oldest son who runs away from Moran’s overbearing authority, never to return. Rejecting his father, Ireland, and all of the violence and provincialism he associates with both, Luke flees to England. He ignores all but one of Moran’s many letters, and he doesn’t return to Ireland except at the end of the novel when his sister gets married. ‘Please don’t do anything to upset Daddy,’ one of the sisters pleads, typically trying to placate her father. ‘Of course not I won’t exist today,’ Luke replies (p.152). His best weapon against Moran’s control is absence. Whereas the daughters, ‘like a shoal of fish moving within a net’ (p.79), find individuality painful compared to the protection of their familial identity, Luke gains strength in departure. ‘I left Ireland a long time ago’ (p.155), Luke announces gravely. As it does for Stephen Dedalus in James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, life in Ireland seems like imprisonment.

‘I’m afraid we might all die in Ireland if we don’t get out fast’ (p.155-156), says Moran’s younger son, Michael. Like other Irish writers, McGahern asks whether exile offers the only hope for freedom and individuality. How does the political turmoil which has long suffused Irish history affect the smaller unit of the family? How do other elements of Irish life contribute to familial dysfunction? In the claustrophobic world McGahern portrays, escape proves sustaining for a character like Luke, but it is not an unequivocal good. Luke is strong but cruel like his father. His sisters, on the other hand, not only fail to break away from the family, but by the time of their father’s death, ‘each of them in their different ways had become Daddy’ (p.183). Their identification with and loyalty to Moran threatens to subsume them, but it also gives them a kind of strength, as Michael seems to understand: ‘In the frail way that people assembled themselves he, like the girls, looked to Great Meadow for recognition, for a mark of his continuing existence’ (p.147).

The Role of Women

(This theme has obviously to be examined in the light of what has already been said about Patriarchy.)

With the exception of Moran and his young son Michael, this story centres on many women characters. Rose Brady is the main character who makes life bearable for everyone in Great Meadow. At every stage she is deeply loyal to Moran and never allows herself to criticise him or his fickle actions in front of the others. She loves him deeply and when he treats her badly she is quick to assert her rights. She does this in a quiet but strong way. She becomes a strong moral power in the house, and through this strength she manages to control Moran and get him to change his bad temperament subtly.

When Moran marries Rose it is obvious that he never intended a marriage of equals. She is to serve as a loyal and devoted second in command and at some future date, when his children have departed, to become his sole subordinate. Rose, a woman in her late thirties at the time of her marriage, is ideally suited to the role of compliant wife and surrogate mother. Her previous profession has been that of valued servant: a children’s nursemaid, and the valet her former master would have chosen had his wife permitted it. She has acquired the social skills that please employers, learned to indulge their whims. That she is good at ironing takes on a metaphorical significance, since she has spent much of her married life ‘smoothing’ out household difficulties. She is attracted by Moran’s aloofness and, ironically, she sees marriage as an opportunity to become mistress of her own establishment. For all his local notoriety as a strategist in the war, Moran doesn’t seem to be able to exercise much control in the matter of his marriage. He is continually out-manoeuvred by Rose, who mounts a shrewd, tactical campaign to get her way when he would prefer to retreat or delay.

Once married, Rose proves to be an angel of the house: a kind, caring, capable homemaker, whose warmth and good humour contrast sharply with Moran’s sudden rages and unpredictable mood swings. Her genuine interest in each child’s welfare contrasts with Moran’s inability to value his children’s individual identity and autonomy. However, it must be said that Rose colludes in perpetuating Moran’s patriarchal regime. She is unfailingly loyal to him and she refuses to entertain his children’s criticism of his petulant behaviour. In his children’s presence she always refers to Moran as ‘Daddy’, the title by which he himself insists that they address him.

Rose’s strategy is to become indispensable to the household. The tea-ceremony on her first evening is very revealing of the future status quo. She takes on the role of a kind of superior servant, co-opting the girls as helpers, and humouring her disgruntled husband by treating him ‘like a lord’:

Rose and the girls smiled as the tea and the plates circled around him. They were already conspirators. They were mastered and yet they were controlling together what they were mastered by. (p.46)

Later on this is viewed in a more negative way:

Then, like a shoal of fish moving within a net, Rose and the girls started to clear the table. (p. 79)

Here the women are seen as victims, trapped in the tense atmosphere which Moran generates. A shift in power relations has occurred and Rose is no longer in control. Her status is now equal with that of Moran’s children.

The power struggle between Rose and her husband centres on two episodes. In the first he is compelled to apologise and she is rewarded with a mini-honeymoon, but she has been made aware of his ‘darkness’ and decides to concentrate her strategy on diverting his attacks – cutting him off at the pass, so to speak. In the second episode he embarks on a prolonged campaign to crush her and she attempts to conciliate and pacify him, until she discovers that she can ‘give up no more ground and live’ (p.71). Her tactic now is to threaten to leave him, a shrewd stroke; since she knows that Moran is already obsessed with Luke’s departure. This power struggle between the two is several times alluded to in military terms. It is a ‘hidden battle’ from which she, apparently, emerges victorious, her objective having been to ensure her ‘place in the house could never be attacked or threatened again’ (p73). What she has settled for, however, is the limited right to be treated like a member of Moran’s family, to swim like a fish in his net.

Moran’s daughters adapt to life by avoiding confrontation. Indeed, there seem to be very limited options in counteracting Moran’s dominance. Compliance, continual confrontation, or departure are the three choices facing Moran’s household. The strategy of the womenfolk, at least, is to ‘slip away’ or try to appear invisible. Such evasion is a tactical manoeuvre, a recognition of their own defencelessness. Beneath their cringing exterior, Mona and Sheila each conceals a forceful character. Mona is ‘unnaturally acquiescent’, ‘full of hidden violence’; Sheila, even as a young child, knows better than ‘to challenge authority on poor ground’. They bide their time until their jobs in the Civil Service set them free from Moran’s daily oppression, though Sheila comes near to confrontation before surrendering her opportunity to attend university. They show their attitude to parental domination in their advice to Michael, to make the best of it until he has finished school and is in a position to choose a career of his own.

In view of their unhappy childhood why do Moran’s children, with the exception of Luke, turn Great Meadow into a place of pilgrimage and their father into a cult figure? What McGahern presents in Amongst Women is the charisma of patriarchy, which consists in its exercise of sole and absolute authority, the power to approve or disapprove, endorse or withdraw support, affirm or reject, and thereby, to nurture an emotional dependency. Though in their last years at home, the Moran children flourish under Rose’s benign dispensation, their primary relationship is with their father. Because his second marriage does not occur until his daughters are in their teens, Rose’s advent does not alter Moran’s status as a dominant single parent, the permanent emotional focus of their lives. They never allude to their dead mother, and the novel ignores the ‘umbilical debt’, according her no influence whatever on their upbringing.

A large part of the fascination the handsome Moran holds for Rose and for his daughters is sexual. Rose loves him; his daughters also experience an ‘oedipal’ attachment. He is their ‘first man’. He looks on their husbands and male friends as rivals and is content when these prove ‘no threat’ to his primal place in their affections. Neither Maggie nor Sheila marry dominant men, and Mona resists marriage altogether. Sheila is the only one to violate this ‘incestuous’ relationship with her father when she leaves him in the hayfield to go indoors and makes love to Sean.

As the novel ends the reader’s sympathies are drawn towards the ailing and dying Moran, so that we share the family’s grief at his death. His corpse is taken to the church on a ‘heartbreakingly lovely May evening’ and buried on a morning when the ‘Plains were bathed in sunshine’ and ‘the unhoused cattle were grazing greedily on the early grass’ (p.182). The sadness of this final parting from the fertile spring world is rendered all the more poignant by the baffled love Moran experiences for his own land in old age. He is shown walking it, ‘field by blind field’, ‘like a blind man trying to see’. In his last month he repeatedly escapes from his sickbed to stare at the beauty of his meadow. At the end of his life Moran eventually arrives at a deep appreciation of the ‘amazing glory he is part of’ (p.179). Maybe this final epiphany is the blessing he always craved and was unable to receive, a blessing hinted at in the name Rose?

GENERAL VISION AND VIEWPOINT

This is a realistic novel, which traces the history of an Irish rural family in the early twentieth century. McGahern focuses on one family and one house and we follow the subtle changes that take place in the comings and goings of various members of the family. He has created a microcosm in Great Meadow from which to view and comment on the changes which have come about after the War of Independence. Even though there is a timeless quality to the novel and no dates are mentioned we are being asked to pass judgement on the new State that has emerged and was beginning to find its feet under the influence of the 1937 Constitution. De Valera’s vision of this New Ireland eulogised the role of women as mothers and home-makers and he painted an idealised picture of life in the Irish countryside:

A land whose countryside would be bright with cosy homesteads, whose fields and villages would be joyous with sounds of industry, the romping of sturdy children, the contests of athletic youths, the laughter of comely maidens; whose firesides would be the forums of the wisdom of serene old age.

McGahern in Leitrim and Kavanagh in Monaghan both knew that the realities of life for poor, farm families were radically different from this version offered by de Valera.

McGahern shows that the power of family bonds to withstand all difficulties is clearly evident throughout every aspect of this story. At the centre of this story is Moran and his wielding of mesmeric power over his children but it obvious also that Rose Brady is truly the moral centre of the novel. It is she who silently manages to improve things within the Moran household, and by doing this she controls a good deal of the violence latent in Moran. It is her undoubted love and loyalty to Moran and her spirit of self-sacrifice in the household, which creates this extraordinary bond of strength which each of the members feel among themselves.

The implication at the conclusion is that Moran’s family is stronger than ever in their love and allegiance to one another. They truly recognise that Moran played a central part in all their lives. Their attendance at his funeral strengthens this bond between them even more. They realise that each one of them, in different ways, has truly imbibed Moran’s beliefs and values. They remain loyal to his person and beliefs in spite of everything. Only Luke remains obstinate in his decision not to return home – a reminder that even he has inherited a great deal of stubbornness and pride from his father.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Sampson, Denis. 1993, Outstaring Nature’s Eye – The Fiction of John McGahern. The Lilliput Press, Dublin.

Quinn, Antoinette. 1991, A Prayer For My Daughters: Patriarchy in Amongst Women in The Canadian Journal of Irish Studies (Special Issue on John McGahern), Volume 17, Number 1, July, 1991

Read also ‘Close Analysis of John McGahern’s ‘That They May Face the Rising Sun’ here

You must be logged in to post a comment.