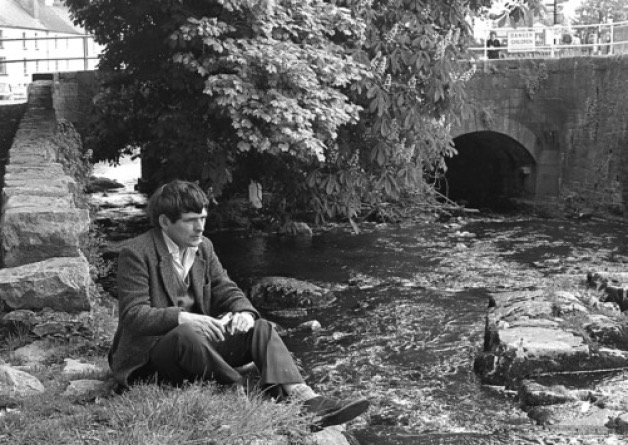

Michael Hartnett arrived back in Newcastle West after nearly fifteen years of ‘exile’, around 1975. He then imposed a further exile on himself by deciding to settle with his wife Rosemary and his two young children, Niall and Lara, ‘out foreign in Glantine’. Thus began one of his most productive periods as a poet – a fact which has been largely overlooked by critics and academics to this very day.

The decade from 1975 to 1985 in Glendarragh, Templeglantine was arguably the most productive of his career. Adharca Broic was published in 1978, followed by An Phurgóid in 1983, Do Nuala: Foighne Crainn in 1984 and his fourth collection in Irish, An Lia Nocht, appeared in 1985. During this period, he also undertook the translation of Daibhi Ó Brudair’s poems which were published in 1985. In parallel to this ‘serious’ output, he was writing and entertaining the locals with ballads, some serious or semi-serious like ‘A Ballad on the State of the Nation’, which was distributed as a one-page pamphlet like the ballads of old and even included original lino cuttings by local artist Cliodhna Cussen. Other ballads were more contentious and even semi-libellous (or fully slanderous!) such as ‘The Balad (sic) of Salad Sunday’ and ‘The Duck Lovers Dance’. These latter creations were written under the very appropriate nom de plume, ‘The Wasp’!

It has to be remembered that at this time Newcastle West and its West Limerick hinterland was booming. The Alcan plant in Aughinish Island near Askeaton was under construction and every man, woman and child were working there. Added to this, every spare room was occupied as up to 4,000 workers from all over Ireland were involved in the construction phase of the project.

In late 1980 Hartnett began work on his best ballad and the one which is most loved and recited to this day, the ‘Maiden Street Ballad’. The ballad stretches out for 47 verses and is a compendium of much of what he had written in prose about Newcastle West in articles for The Irish Times, for Magill magazine and for the local Annual Observer, the annual publication of the Newcastle West Historical Society during the 60s and early 70s. There are also echoes of other local poems such as ‘Maiden Street’ and ‘Epitaph for John Kelly, Blacksmith’ included among the verses of the ballad.

In his own mind, Hartnett had lofty ambitions for the project – the ballad was to be Newcastle West’s own Cannery Row. Indeed, in the Preface to the ballad Hartnett wrote of his affection for his home place:

Everyone has a Maiden Street. It is the street of strange characters, wits, odd old women and eccentrics; also a street of hot summers, of hop-scotch and marbles: in short the street of youth. But Maiden Street was no Tir na nÓg … Human warmth and poverty often go hand in hand … The object of this ballad is to invoke and preserve ‘times past’ and to do so without being too sentimental … But this ballad is not all grimness. I hope it is humorous in spots. It was not written in mockery but with affection – part funny song, part social history.

‘Maiden Street Ballad’ was published by local entrepreneur Davy Cahill and his The Observer Press ‘with the help of members of Newcastle West Historical Society’. Copies of the original are much sought after on eBay and elsewhere to this day. It carried a very eloquent dedication, ‘This ballad was composed by Michael Hartnett in Glendarragh, Templeglantine, County Limerick in the month of December 1980 as a Christmas present for his father Denis Harnett (sic)’. His long-time friend and fellow poet, Gabriel Fitzmaurice is fulsome in his praise for the ‘Maiden Street Ballad’:

… it is unquestionably the best ballad he wrote during this period. It is a celebration of his native place in which he describes mainly the period 1948 – 51, the time of his childhood; it also describes the Newcastle West of the late 1970s during which time he lived in Templeglantine (McDonagh/Newman, p.107).

‘Maiden Street Ballad’ was set to the air of ‘The Limerick Rake’ which Hartnett himself described as ‘the best Hiberno-English ballad ever written in this country’. Hartnett was drawing on a rich tradition of local balladeers ‘like Aherne and Barry before me’, but there are also echoes here of Patrick Kavanagh and such ballads as ‘If Ever You Go to Dublin Town’. It is a matter of record that after early skirmishes in various hostelries in Dublin in the early 60s both Hartnett and Kavanagh came to an understanding and Hartnett tells us, ‘I used to drink with him and indeed back horses for him (he owes me £3-10s for the record)’ (O’Driscoll interview, p.144).

Writing in The Irish Times, June 10, 1969, Hartnett relates a story about his father which may have sown the seeds for the famous virtual pub-crawl which is such a central feature of ‘Maiden Street Ballad’ and which is the focus of this essay. Speaking about his relationship with his father he recalls:

I sat there in the small kitchen-cum-living room, innocently working out the problems my father set me: ‘If it took a beetle a week to walk a fortnight, how long would it take two drunken soldiers to swim out of a barrel of treacle?’ I never worked it out. Or, “How would you get from the top of Church Street to the end of Bridge Street without passing a pub”? He did supply the answer to that, which indeed is the logical answer for any Irishman: “You don’t pass any – you go into them all.”

‘Maiden Street Ballad’ contains a number of autobiographical segments; from his early days in Lower Maiden Street where they rented from Legsa Murphy; then later he eloquently documents the move to the new housing scheme in Assumpta Park. However, the most notorious segment is the ten ribald verses from 27 to 37 which describe a virtual pub crawl of all of Newcastle West’s 26 public houses which were doing business in 1980. These verses portray Hartnett at his best, they are witty, they are caustic, they are slanderous; they poke fun at his friends, and especially at his brothers and cousins. BUT there is also great sadness.

The ‘pub crawl’ begins in Stanza 27 and the poet bemoans the fact that he visits too many pubs. The first pub mentioned is Dinny Pa’s, owned and run by Dinny Pa Aherne. The pub was situated where The Weekly Observer now has its offices. In more recent times this pub was owned by another doggie man, Ted Danaher from Knockaderry. By the way, the present pub known as The Forge which was next door to Dinny Pa’s is not mentioned in the Ballad because it was closed at the time and has only reopened in recent years. This pub was originally the property of J.J. Hough and his wife Nora (nee Dore). The pub was subsequently bought by John Sullivan from Killarney and he eventually sold it on and it has had a number of incarnations in recent years. Next, he mentions The Silver Dollar in Lower Maiden Street, which was originally owned by Bill Flynn. By the 1970s The Silver Dollar had been passed down to his daughter Margaret and her husband John Kelly who was originally from Broadford and who was at that time a Fine Gael County Councillor. He then takes a big jump to the other side of town and mentions Mike Flynn’s in Churchtown, now The Ballintemple.

In Stanza 28 he mentions four more pubs beginning with McCarthy’s in Maiden Street which was owned by John McCarthy and his wife, Clare Finucane, and was known then as The Tall Ships (today trading as Ned Kelly’s). He then mentions a cluster of three pubs just off The Square, heading up Churchtown. Pat Whelan was by 1980 probably one of the most successful publicans in the town and he ran a very successful pub next door to what was then Crowley’s Drapery. Directly across the road was The Greyhound, owned and run by Lena Barrett. Finally, by all accounts, the poet nearly landed himself in choppy legal waters with the line, ‘and I have been known to peep in to Peep Outs’. Seemingly the owner was known to occasionally peep out to see if there were any prospective customers on their way and, like many other unfortunates in the town quickly gained a none too complimentary nickname for his troubles. In an effort to give his ballad added gravitas Hartnett added some ‘scholarly’ footnotes (to the first 20 verses only) and in one he tells us that, ‘It used to be said that if a stranger walked from Forde’s Corner (now Burke’s Corner at the junction of The Square and Upper Maiden Street) he’d have a nickname before he got to Leslie’s Ating House (where, in recent years, Dickie Liston had his shop in ‘Middle’ Maiden Street)’.

In Stanza 29 he mentions two other pubs who were making waves in the town in the late 70s. Tom Meaney was doing a roaring trade in The Turnpike – also the venue for Zanadu’s Nite Club – and to encourage punters he held quizzes on Sundays in which Des Healy and Joe White excelled. He also mentions Mike Kelly who at that time was running the Ten Knights of Desmond pub in the Square. He was leasing the pub from Jimmy and Mary Lee and the pub is now being run by their son, Joe. Mike Kelly was endeavouring to raise standards and expectations and so had peanuts and cheese available for his ‘better-class clients’ who ‘dine free there on Sundays, the chancers’.

Stanza 30 mentions The Tally-Ho and this was situated across the road from the Carnegie Library which at that time housed St. Ita’s Secondary School, owned and managed by Jim Breen and which, of course, had been Hartnett’s alma mater. Some ruffians in the town claimed that The Tally-Ho was the unofficial staff room for St. Ita’s – but that’s for another day! He tells us he’d ‘go there more often but Mike Cremin sings’. Nearby on the corner was John Whelan’s pub. John was Pat Whelan’s father and was a legend in GAA circles having given a lifetime to Newcastle West, West Board and County Board administration. This was the local of Hartnett’s ‘cousin’ Billy O’Connor, or Billy the Barber as he was better known and who was, in fact, married to Hartnett’s aunt, Kit Harnett.

In Stanza 31 he doesn’t name a pub but I presume he is still in The Corner House with his relations and various ‘cousins’! Hartnett’s brother, Dinny was a postman in town at this time and Michael makes sure to mention Dinny a number of times, and not always in glowing terms. Here he joins his brother, and some of Dinny’s colleagues, Tony Roche and Davy Horan for a session. The Christmas flavour of the ballad is maintained when he says, ‘You can hear Dinny laugh miles up the Cork Road / as he adds up his Christmas donations!’.

Stanza 32 is dedicated to Barry’s Pub in Bridge Street. He describes the pub as being a little above the ordinary. Of course, we must remember, many of these recommendations were given with a view to future free pints, post-publication! However, the opposite could also be the case and after the publication of the infamous, ‘The Balad of Salad Sunday’, Hartnett rather ruefully declared that as a result ‘I was barred from thirteen pubs’.[1] According to the poet, John and Peg Barry ran a classy establishment and ‘if you want to read papers you don’t buy at home’ or if ‘you want a hot whiskey with more than one clove’ then you should give them a call!

Stanza 33 is dedicated to another favourite of Hartnett’s, The Shamrock Bar in South Quay. In the late 70’s Damien Patterson and Tony McCarthy undertook an extensive renovation of Fuller’s Folly, part of the Desmond Castle complex and fronting on to the Arra River near the bridge at the bottom of Bridge Street. Indeed, to add to their conservation work Tony McCarthy and others decided that they would introduce different species of duck to the river to enhance its attractiveness. This project, years ahead of its time, entailed setting up a breeding programme and sourcing young ducklings and, as a consequence, this gave rise to numerous fundraising ventures. The Duck Lovers Committee set up their headquarters in The Shamrock Bar, managed at the time by Tony Sheehan and his wife, Peg (nee Devine), who were both immortalised by Hartnett in his ballad, ‘The Duck Lovers Dance’. The Shamrock was later acquired by George Daly and his wife Breda and Hartnett was a regular there and benefitted from their generosity and patronage. In return, he penned a beautiful song in their honour, ‘Daly’s Shamrock Bar’.

Hartnett had come back home to find and nurture his Gaelic roots and to immerse himself in the language and traditions of the past. Here at home, he was universally known as ‘The Poet’ and this title was bestowed on him as a nickname of honour. However, like the old Gaelic poets such as Ó Brudair, Ó Rathaille, Sean Ó Tuama and Aindreas MacCraith before him, being mentioned by the poet could make you famous for all the wrong reasons. Suffice it to say that sometimes it was an honour to have a poet in your midst during a drinking session but you needed to be on your best behaviour or you could be shamed for life. For example, Hartnett tells us that in The Shamrock, ‘You’ll see Jimmy Deere and he making soft farts, / you’ll see Terry Hunt, he’s a martyr for darts – / he spends every weeknight nearly bursting his arse / to bring home a ham or a turkey.’!

Stanza 34 mentions seven iconic public houses. Many of these were very small premises and they also sold groceries and other items to their loyal patrons. For example, the poet says he usually, but not exclusively, visits Donal Scanlon’s in Upper Maiden Street ‘when the new spuds come in’. It is interesting that in South Quay you had four pubs probably within a hundred metres of each other – Seamus Connolly’s, The Shamrock, Gerry Flynn’s and The Crock of Gold, owned by Moss Dooley. All but one remains today – Gerry Flynn’s is now Clery’s having been owned by Paddy Sammon for a while and then being won in a raffle sometime before the Celtic Tiger began to roar in earnest! He also mentions Walsh’s which was situated on the corner of Lower Bridge Street and North Quay. This imposing pub has recently undergone major renovations but regrettably is not open for business at present. Cremin’s was in Upper Maiden Street where The Dresser now carries on business. This pub had somewhat of a coloured reputation and was run by the Cremin sisters, Nora, Mary, Gretta and their mother. Gretta Cremin was also for many years the church organist in the nearby parish church He also mentions The Heather in Bridge Street which was owned and run by the Duggan family. However, today Hartnett’s statue in The Square points longingly across to Ned Lynch’s, still run by the man himself, the last survivor of the old stagers.

Stanza 35 mentions two other very well-known pubs – Dan Cronin’s pub in the Square and Cullen’s in Upper Maiden Street. Cullen’s was formerly known as Dolly Musgraves (Gearoid Whelan, son of Pat and grandson of John, carries on the tradition today on this site in a newly refurbished Sports Pub). Dolly Musgraves pub had a special place in Hartnett’s affections because he tells us that it was here (in the company of his great friend and partner in crime, Des Healy) that he had his first pint – no names, no pack drill, but suffice it to say they were barely out of short pants! He also fondly remembers The Sunset Lounge in The Square (later to become the TSB Bank premises and now Ladbrokes Betting Office) which was owned by Bill Hinchy and his wife Kit. Hartnett tells us that he had many fond memories of playing chess there with Bill Buckley. Finally, as if by way of a postscript he mentions the bar in The Motel which was a bit out of the way being situated on the main Limerick – Killarney Road. He tells us that he didn’t frequent this bar too often because of its political links to Fianna Fáil – Mike himself being a tried and trusted paid-up member of The Labour Party!

Stanza 36 mentions the final two bars close to his heart – The Central Hotel which at that time was owned and run by Arthur and Vera Ward. It had been known as Egan’s Hotel at one time and even though the title Hotel still remained it was really only a bar – today it trades simply as The Central Bar. Last but not least he mentions Seamus Connolly’s little pub in South Quay. Hartnett’s fondness for Seamus Ó Conghaile was obvious because he could speak Irish and after his proclamation on the stage of the Peacock Theatre in 1974, Hartnett had returned home with the express intention of henceforth writing only in Irish. He was, therefore, doubly glad of every opportunity to frequent Seamus Connolly’s to imbibe at ease in convivial company and also improve on his Irish language skills.

Stanza 37 ends this section of the Ballad and Hartnett hopes that we won’t consider that he is ‘mad for the drink’! During the virtual tour of all the 26 pubs in town, he has been wistful and rueful, and only his true friends and relations have felt the full brunt of his devilment and ball-hopping. Others elsewhere in the ballad, such as employers and charitable institutions do not escape the cold breeze of his displeasure but here he is among friends and in his element. However, it also has to be said that these verses also tend to paper over the cracks that were beginning to appear in Hartnett’s serious project – to return to his roots in West Limerick and to write only in Irish. He was drinking heavily by this time and his marriage to Rosemary was beginning to show signs of strain. The Ballad is dedicated to his father, Denis Harnett, with love and gratitude. It has to be seen as a poet’s gift, a poet who was penniless with little else to give except his considerable talent as a poet and who was now finally writing ‘a few songs for his people’. His father Denis passed away in 1984 and shortly afterwards his marriage came to its inevitable conclusion and Hartnett left his hometown for good to return to Dublin. So, for me, reading the Ballad today, and despite the jokes and the jibes and the critical social commentary, the overriding emotion is one of sadness.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that there were 56 pubs in Newcastle West in the 40s and 50s. However, the years have passed, the Celtic Tiger has come and gone in Newcastle West and today, instead of the 26 pubs that were doing business in 1980 there are only 11 open for business – and as I mentioned earlier this figure includes The Forge which didn’t feature in Hartnett’s original 26 because it was not trading in 1980! If you wanted to do the ‘Twelve Pubs at Christmas’ in Newcastle West today you’d have to end up in Hanley’s in Knockaderry for your twelfth! Or maybe the Golf Club in Ardagh?

I mentioned earlier his father setting the young Hartnett a riddle: “How would you get from the top of Church Street to the end of Bridge Street without passing a pub”? In 1975 if you were to visit all the pubs from the top of Churchtown to the end of Bridge Street you would have had to visit nine pubs in all, today in 2019 the number has been reduced to three (if you pass by both banks on your way through The Square) – The Ballintemple, recently under new management, The Central in Bridge Street, and last but not least, Ned Lynch’s in The Square! If you take the long way round The Square you can add in Dan Cronin’s and Lee’s!

Alas, Shane Ross, our Minister for Transport, Tourism and Sport, has been instrumental in ensuring that the pub trade in rural Ireland has seen better days and the old dispensation is no more. In a radio interview on WLR 102 on 26th September 2019 to promote the upcoming Éigse, Gabriel Fitzmaurice recalled a journey home to Glendarragh with Michael Hartnett in the late 70s after having visited a number of the hostelries mentioned earlier in this article. Gabriel was acting as a willing chauffeur on this occasion and on their way up Old Bearna, Michael turned to him and said: ‘Gabriel, for God’s sake, take it easy – the future of Irish poetry is in this car’.

‘Maiden Street Ballad’ today stands as a unique piece of social history as well as being a very beautiful, and funny poem, which I would strongly urge you to read or re-read. (The full Ballad, including ‘scholarly’ footnotes, is included in The Book of Strays, published by Gallery Books in 2002 and reprinted in 2015). Many of Hartnett’s prose pieces for The Irish Times and elsewhere in the 70s show him to be an astute and acerbic social commentator and we can also see clear evidence of this in the 47 verses of ‘Maiden Street Ballad’:

And in times to come if you want to dip

back into the past, through these pages flip

and, if you enjoy it, raise a glass to your lips

and drink to the soul of Mike Hartnett!

I would like to acknowledge the encyclopaedic help received from Sean Kelly and his wife Mary in compiling this piece of nostalgia!

Author’s Note: Sadly, since this post was published in December 2019 three of the eleven pubs still surviving have ceased trading – The Forge fell foul of the taxman, The Ballintemple Inn was badly damaged in a fire and Ned Lynch’s didn’t reopen following the first Covid -19 Lockdown of 2020. So, for Christmas 2023 there are only eight of the 26 pubs much beloved of Hartnett in 1980 still trading.

Footnotes

[1] In an interview with James Stack in 1987 as part of James’s thesis for his degree in English from UCG. Audio available in Memories from the Past: Episode 305

Works Cited

McDonagh, J. and Newman, S., Remembering Michael Hartnett. Dublin, Four Courts Press, 2006.

O’Driscoll, Dennis., Interview with Michael Hartnett, in Metre, Issue 11, Winter 2001-2002

You must be logged in to post a comment.